By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: August 12, 2020 ~

On May 30, with little mainstream media attention, four European academics published a report on how some of the largest Wall Street banks (all of whom received massive amounts of secret Federal Reserve bailout money during the 2007 to 2010 financial crash) were shamelessly gaming the system again.

On May 30, with little mainstream media attention, four European academics published a report on how some of the largest Wall Street banks (all of whom received massive amounts of secret Federal Reserve bailout money during the 2007 to 2010 financial crash) were shamelessly gaming the system again.

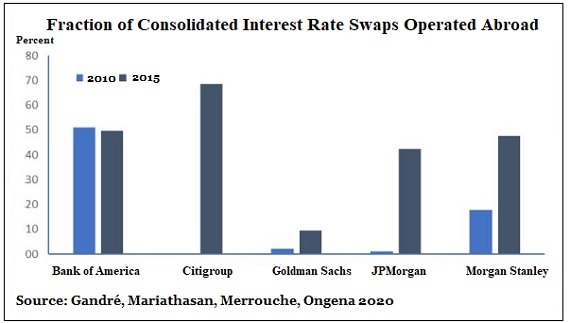

Rather than complying with the derivatives regulations imposed under the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010, the Wall Street mega banks had simply moved much of their interest rate derivatives trading to their foreign subsidiaries that fall outside of U.S. regulatory reach. This is known as regulatory arbitrage: seeking the most lightly regulated jurisdiction to ply your dangerous trading activity. (Think JPMorgan’s London Whale fiasco.)

The European academics are Pauline Gandré, Mike Mariathasan, Ouarda Merrouche and Steven Ongena. The paper is titled: “Regulatory Arbitrage and the G20’s Global Derivatives Market Reform.”

The researchers discovered that “US banks reduced their [derivative] holdings at home, while increasing them in Australia, Japan, the UK, Brazil, China, Hong Kong, and Mexico.”

The poster child for becoming a financial basket case in 2008, Citigroup, was called out particularly in the report. Citigroup had gone from no interest rate derivatives at its foreign subsidiaries in the fourth quarter of 2010 to over 60 percent by the fourth quarter of 2015. JPMorgan Chase went from about zero percent to more than 40 percent from the fourth quarter of 2010 to the fourth quarter of 2015. Both Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley more than doubled their foreign subsidiary exposure to derivatives during the same time frame.

During the last financial crisis, Citigroup received the largest bailout in global banking history, grabbing $45 billion in capital from the U.S. Treasury; over $300 billion in asset guarantees from the federal government; the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) guaranteed $5.75 billion of its senior unsecured debt and $26 billion of its commercial paper and interbank deposits; and the Federal Reserve secretly made a cumulative $2.5 trillion in below market interest rate loans to Citigroup from 2007 through at least the middle of 2010, according to an audit by the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

According to documents released by the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC), at the time of Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy on September 15, 2008, it had more than 900,000 derivative contracts outstanding and had used the largest banks on Wall Street as its counterparties to many of these trades. The FCIC data shows that Lehman had more than 53,000 derivative contracts with JPMorgan Chase; more than 40,000 with Morgan Stanley; over 24,000 with Citigroup’s Citibank; over 23,000 with Bank of America; and almost 19,000 with Goldman Sachs. These are the same Wall Street mega banks shown on the chart above that are now evading Dodd-Frank derivative rules by moving large amounts of their opaque derivative trades to their foreign subsidiaries.

Another chart from the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission that will take your breath away shows the derivatives casino that Goldman Sachs had become by June of 2008. The figures are simply staggering. In the most dangerous form of derivative, credit derivatives, Goldman Sachs had $5.1 trillion notional (face amount) exposure. And almost all of its counterparties were being propped up by the Federal Reserve’s secret revolving loans. In the case of Merrill Lynch and Morgan Stanley, where Goldman had more than $600 billion exposure to each counterparty, the Fed made $2 trillion in secret, cumulative, below-market rate loans to each firm, according to the GAO audit.

Because of the pivotal role that derivatives played in the Wall Street collapse of 2008, which spawned millions of foreclosures and job losses across the U.S., the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation was supposed to prevent insured depository banks from holding these dangerous derivatives. One derivatives reform measure was known as the “push out rule,” where derivatives would be pushed out of the insured bank to a different part of the bank holding company that could be wound down without taxpayer support if the bank became insolvent. But before that rule ever took effect, Citigroup engineered its repeal.

Another measure in the Dodd-Frank legislation required that derivatives move from over-the-counter contracts between two private counterparties to a central clearing facility in order to remove counterparty default risk from causing systemic contagion in the financial system as it did in 2008. It’s been more than 10 years since Dodd-Frank was signed into law. By now, the vast majority of derivative trades should be centrally-cleared. Instead, this is what the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency reports as of March 31, 2020:

“In the first quarter of 2020, 42.3 percent of banks’ derivative holdings were centrally cleared. From a market factor perspective, 52.9 percent of interest rate derivative contracts’ notional amounts outstanding were centrally cleared, while very little of the FX [foreign exchange] derivative market was centrally cleared. The bank-held credit derivative market remained largely uncleared, as 34.4 percent of credit derivative transactions were centrally cleared during the first quarter of 2020.”

The mega Wall Street banks have been getting minor slaps on the wrist and insignificant fines over their derivative violations under the Trump administration. On September 25, 2017, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) fined Citigroup $550,000 for failing to properly report derivative trades. One of the violations was defined as follows: “…Citi violated its reporting obligations by reporting ‘Name Withheld’ as the counterparty identifier for tens of thousands of swaps with counterparties in certain foreign jurisdictions.”

In October 2017, for the second time in two years, the Financial Conduct Authority in the U.K. fined Bank of America’s Merrill Lynch for failure to properly report its derivative trades. The action resulted in a fine of £34,524,000 over Merrill’s failure “to report 68.5 million exchange traded derivative transactions between 12 February 2014 and 6 February 2016.” Exactly how does one forget to report 68.5 million transactions? Forgive us for thinking it’s a feature, not a bug.

A decade after the worst collapse of iconic Wall Street institutions in history and the largest Federal Reserve bank bailouts in global banking history, there is very little to show in the way of meaningful reform. Without the restoration of the Glass-Steagall Act, Wall Street’s wealth transfer system, that plunders the 99 percent in service to the 1 percent, will continue humming along.