By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: October 15, 2019 ~

The mega banks on Wall Street report earnings this week led off by JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, Citigroup and Wells Fargo this morning.

The mega banks on Wall Street report earnings this week led off by JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, Citigroup and Wells Fargo this morning.

Among the items of interest in JPMorgan Chase’s written presentation was that it spent $6.7 billion in this past third quarter buying up its own stock and thus boosting its stock price artificially beyond outside investor demand. The third quarter buybacks of its stock came on top of spending $5 billion in the second quarter and $4.7 billion in the first quarter, bringing its net repurchases of its own stock just so far this year to a whopping $16.4 billion — money that could have otherwise gone to loans to small businesses to kickstart innovation and job growth in America.

This Thursday, the House Financial Services’ Subcommittee on Investor Protection, Entrepreneurship and Capital Markets will hold a hearing on stock buybacks by publicly traded corporations. The hearing will make the following points: there’s nothing normal about corporations inflating their share price through buybacks – in fact, the practice was illegal in the United States prior to 1982. The second point is that buybacks come at the expense of legitimate uses of corporate cash such as boosting stagnant worker wages, investing in new equipment or research and development.

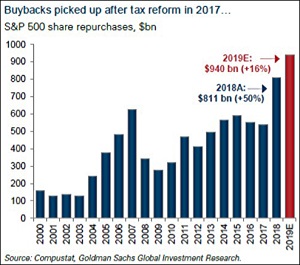

Buybacks are also seen as abusive forms of stock price manipulation and the SEC has no meaningful programs to police how and when these transactions occur. The Subcommittee notes that buybacks have skyrocketed from less than $200 billion in 2000 to a record $811 billion last year. The mega banks on Wall Street are responsible for a big chunk of those dollars.

Another of the craziest aspects of this uniquely corrupt period in American banking is that Wall Street’s brokerage firms and investment banks have combined with deposit-holding, federally-insured banks – giving the so-called “universal” banks the potential to use savers’ deposit money to artificially inflate their own stock through buybacks. That’s really crazy. But what is even crazier is that the SEC is also allowing these mega banks to trade in their own stock in their own Dark Pools, the equivalent of an in-house stock exchange. (See Wall Street Banks Are Trading in Their Own Company’s Stock: How Is This Legal?)

Another unprecedented and totally crazy aspect of today’s banking scene is that criminal felony charges no longer matter. You can be a bank like JPMorgan Chase, holding $1.6 billion in deposits for risk-adverse savers, while also being regularly charged with crimes. You never have to say “I’m sorry” to your shareholders because all they seem to care about is their stock price and the company is propping that up with stock buybacks that have been legalized. JPMorgan Chase is a 3-count felon and just last month one of its trading desks was labeled a criminal enterprise by the U.S. Department of Justice. On the same day, three of its precious metals traders were indicted on RICO charges, a statute typically reserved for organized crime. Throughout the past decade of felony counts and $36 billion in fines for wrongdoing and losing $6.2 billion in depositors’ money in a crazy derivatives scheme in London (the London Whale debacle) the Chairman and CEO of the bank, Jamie Dimon, has kept his job, being allowed by his media sycophants to achieve icon status. (See Will Jamie Dimon Finally Lose His Job Over Racketeering Charges?)

It really can’t get any crazier than all this – and yet it actually does.

Despite repeated warnings from the very agency created under the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010 that followed the greatest Wall Street crash since the Great Depression, deposits and risks are now concentrated in just five banks in the U.S. out of the more than 5,000 banks and savings associations located in the U.S. The Office of Financial Research (OFR), before its budget and staff were gutted by the Trump administration, repeatedly warned that the concentrations of risks among these five banks were going to end badly.

According to OFR research in 2015:

“The larger the bank, the greater the potential spillover if it defaults; the higher its leverage, the more prone it is to default under stress; and the greater its connectivity index, the greater is the share of the default that cascades onto the banking system. The product of these three factors provides an overall measure of the contagion risk that the bank poses for the financial system. Five of the U.S. banks had particularly high contagion index values — Citigroup, JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, and Goldman Sachs.”

The risks have not subsided since 2015, they have gotten exponentially larger. According to the most recent quarterly report from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Federal regulator of national banks, Goldman Sachs’ total credit exposure from derivatives to capital stands at 372 percent. JPMorgan Chase’s stands at 150 percent while Citigroup’s registers 132 percent. Not to put too fine a point on it but Citigroup, just a decade ago, blew itself up with derivatives and off-balance-sheet toxic time bombs and received the largest bank bailout in the history of global banking.

This is what it took to resuscitate Citigroup, a bank that no outsider, including sitting President Barack Obama, wanted to see resuscitated: Citigroup received a government guarantee on over $300 billion of its assets; a $45 billion taxpayer infusion in equity capital; the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation guaranteed $5.75 billion of its senior unsecured debt and $26 billion of its commercial paper and interbank deposits; and the Federal Reserve, the nation’s central bank, secretly sluiced over $2.5 trillion in revolving loans to Citigroup, from December 2007 through at least July 2010. Significant portions of the Fed’s secret loans to Citigroup occurred at a time when the bank was clearly insolvent. The Federal Reserve is not legally allowed to make loans to insolvent institutions.

Which brings us to the very latest, craziest episode in this uniquely corrupt era of banking in the United States. Since September 17 of this year, the Federal Reserve has once again turned on its secret spigot to Wall Street. It’s pumping hundreds of billions of dollars each week to Wall Street stock trading firms (not commercial banks) with no authorization or hearings occurring in Congress. This is the first time the Federal Reserve has acted in this fashion since the epic financial crash of 2008 but this news isn’t making it to the front pages of newspapers anywhere in America, effectively making corporate media a co-conspirator with the U.S. central bank and Wall Street. (See There’s Nothing Normal About the Fed Pumping Hundreds of Billions Weekly to Unnamed Banks on Wall Street: “Somebody’s Got a Problem”)

The “universal bank” model has become so riddled with moral hazard and conflicts of interests and quid-pro-quo dealings that Wall Street’s core functions of prudent capital allocation and allowing free markets to serve as a pricing mechanism are more broken than ever. We had a crazy company like WeWork this year attempting to do an initial public offering at a $50 to $60 billion valuation and it couldn’t get it done at even $12 billion. We say the company is crazy because it’s taken on $47 billion in long-term real estate leases while risking its future profits and revenues and very survival on short-term subleases, many of which are to young start-ups and freelancers who are highly likely to cut and run in the next downturn.

And, of course, JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs were happy to serve as the lead underwriters in that highly questionable IPO, which has now been abandoned simply because reporters took the time to dig into the offering prospectus. (See The Dickensian Tale of the WeWork IPO.)

Attempting to recover from the epic Wall Street financial crash of 2007-2010 without restructuring the corrupted banking model on Wall Street is having dire economic outcomes around the world. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, global government debt between 2007 and 2019 has doubled with the debt-to-GDP ratio skyrocketing from 49.5 percent to 72.6 percent. Debt-to-GDP now exceeds 100 percent in Japan, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Belgium, France, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States.

According to Trading Economics, “The United States recorded a government debt equivalent to 106.10 percent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product in 2018. Government Debt to GDP in the United States averaged 62.31 percent from 1940 until 2018, reaching an all time high of 118.90 percent in 1946 [as a result of World War II] and a record low of 31.80 percent in 1981.”

Research from the World Bank concludes that countries whose debt-to-GDP ratios remain above 77 percent over the long-term will see material slowdowns in economic growth. The United States has been stuck in an annual 2 percent or lower GDP growth-rate since the financial crisis.

The lack of accountability on Wall Street and within the Federal Reserve is beginning to register in the minds of investors. According to a report on October 12 at CNBC, investors are making a dash to the liquidity of money market funds “at the highest level since the financial crisis-era collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008.” According to the report, money market balances have swelled by $322 billion in the past six months.