By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: January 4, 2021 ~

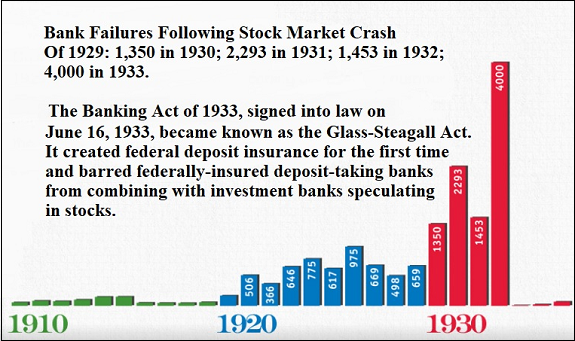

Following the stock market crash in 1929, more than 9,000 banks in the United States failed over the next four years. In just the one year of 1933, more than 4,000 banks closed their doors permanently as a result of insolvency.

The 1930s banking crisis came to a head on March 6, 1933, just one day after President Franklin D. Roosevelt was inaugurated. Following a month-long run on the banks, Roosevelt declared a nationwide banking holiday that closed all banks in the United States. On March 9, 1933 Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act which allowed regulators to evaluate each bank before it was permitted to reopen. Thousands of banks were deemed insolvent and permanently closed. It is estimated by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) that depositors lost $1.3 billion to failed banks in that era. That would be approximately $25.5 billion in today’s dollars.

To restore the public’s confidence in placing their savings in banks, Roosevelt signed into law on June 16 the Banking Act of 1933, more popularly known as the Glass-Steagall Act after its authors Senator Carter Glass, a Democrat from Virginia, and House Rep Henry Steagall, a Democrat from Alabama. The legislation created federal deposit insurance for bank accounts for the first time in the U.S. while banning banks speculating in or underwriting stocks to hold deposits.

This separation of banking was not controversial at the time. Years of Senate hearings following the ’29 crash had informed the Congress of that era, as well as the public, that Wall Street’s casino banks gambling with depositors’ money in wild stock speculations had caused the stock market crash and ensuing run on the banks.

The Glass-Steagall Act protected the U.S. banking system for 66 years until its repeal during the Bill Clinton presidency in 1999. The impetus for its repeal was the announcement in 1998 that Sandy Weill wanted to merge his trading firms, Salomon Brothers and Smith Barney (under the Travelers Group umbrella), with Citicorp, parent of the federally-insured Citibank commercial bank. (See Pam Martens’ testimony before the Federal Reserve against this merger and the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act.)

Weill had a singular motive for this merger, which created the Frankenbank, Citigroup – and it wasn’t to advance the nation’s interests. Weill told his merger partner, John Reed of Citibank, that his motivation for the deal was: “We could be so rich,” according to Reed in an interview with Bill Moyers.

The repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999 meant that the casino-style investment banks and trading houses across Wall Street could now own federally-insured commercial banks and use their hundreds of billions of dollars in insured deposits to speculate in stocks and derivatives. Every major Wall Street trading house either bought a federally-insured bank or created one.

What Weill meant by “We could be so rich” was this: If the trading bets won big, the bank CEOs became obscenely rich on stock-option-based performance pay. When the bets lost big, the government would be forced to do a bailout rather than allow a giant, interconnected, federally-insured bank to fail. (You can read about Weill’s Count Dracula stock option/get-rich-quick plan here.)

Just nine years after the repeal of Glass-Steagall, Wall Street blew itself up again and the government had to step in with a massive bailout for the deposit-taking banks that had merged with Wall Street’s investment banks and brokerage firms. In addition to the government bailout, the Federal Reserve, which was supposed to be the regulator of these mega bank holding companies, morphed into the secret sugar daddy of the mega banks. Without one vote in Congress, the Fed secretly funneled $29 trillion in cumulative loans to bail out the casino banks, including their trading operations in London.

The Federal Reserve has been demonstrating this Stockholm Syndrome with the abusive banks it “regulates” ever since. (See our archive of articles on the Fed’s ongoing bank bailouts that began on September 17, 2019, prior to the pandemic, here.)

Both Weill and Reed did, indeed, become obscenely rich. (Weill walked away as a billionaire). Weill’s progeny, Citigroup, meanwhile received the largest taxpayer bailout in U.S. history, taking in $45 billion in equity from the U.S. Treasury; a government guarantee on $300 billion on Citigroup’s dubious assets; the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) guaranteed $5.75 billion of its senior unsecured debt and $26 billion of its commercial paper and interbank deposits; and the Federal Reserve secretly funneled $2.5 trillion cumulatively in low-interest loans to units of Citigroup from December 2007 to at least July 2010.

The unprecedented nature of the Fed’s bailouts of these casino banks holding trillions of dollars of insured deposits did not become fully known until 2011 when a media court battle with the Fed won the release of part of the information and a government audit of the Fed released more details. Nor was the official report of the corruption on Wall Street and regulatory failures that had led to the crisis released by the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission until 2011.

By that time it was too late. Congress had enacted the toothless Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation on July 21, 2010. Instead of restoring the desperately-needed Glass-Steagall Act, the bill tinkered around the edges of reform, with Wall Street’s legions of lobbyists confident that Wall Street could steamroll right through any speed bumps – which it did in short order.

As a result of that Faustian bargain in 2010, Americans are living now with the same casino banking model as existed in the leadup to the crash of 2008. Making matters worse, Wall Street is escaping blame for the current financial crisis (thus far anyway) as its sycophants in Congress are blaming the financial troubles on the pandemic.

Until there is a thorough investigation by an independent body into today’s Wall Street casino banks, Americans will remain in the dark about this banking model from hell.