By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: September 12, 2019 ~

Yesterday the U.S. House of Representatives’ Subcommittee on Investor Protection, Entrepreneurship, and Capital Markets held an extremely timely hearing titled: “Examining Private Market Exemptions as a Barrier to IPOs and Retail Investment.” The thrust of the hearing was the negative impact that the ballooning private equity market is having on the dramatically shrinking pool of publicly traded stocks and the good of society in general.

As the WeWork IPO train wreck plays out in the media, showing how two of the most sophisticated banks on Wall Street, JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs, were set to bring this 9-year old office rental company to the public markets via an IPO, despite outrageous conflicts of interest by WeWork’s founder and CEO and a proposed valuation that turns out to have been off the mark by tens of billions of dollars, it was certain that someone was going to bring up WeWork at this hearing. That person was Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York.

Ocasio-Cortez asked Duke University Law Professor Elisabeth de Fontenay, one of the witnesses who testified yesterday, about the kinds of protections retail investors would have if private equity markets were broadened to include retail investors. Professor de Fontenay explained that the small investor would rarely have access to audited financial statements, no ability to accurately assess the valuation of the company, and no information on any criminal investigations taking place – all of which is available for a publicly listed company.

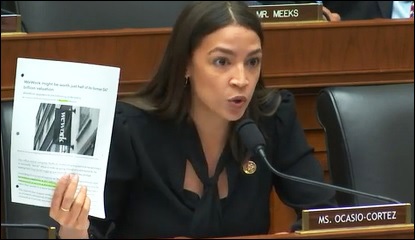

Ocasio-Cortez then waved a news article bearing WeWork’s name and said “They had raised on a previous valuation of $47 billion and now they just decided overnight, just kidding, we’re worth $20 billion. They’ve cut it by over half. Correct?”

Renee Jones, the Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and Law Professor at Boston College Law School took that question. She said valuations of private companies tend to be highly speculative.

Ocasio-Cortez said that if you had invested in WeWork thinking it had a valuation of $47 billion, “you’re getting fleeced.”

In Jones’ prepared testimony, she explained how deregulation has led to “the wholesale reshaping of both public and private securities markets, and the emergence of a new class of companies, so-called unicorns, that lack the kinds of mechanisms for management accountability that investors in public and private companies have come to expect…” Jones noted that the deregulatory changes in the law “have enabled startup companies to fund their operations and sustain massive losses, all while avoiding the scrutiny that comes from accessing the public equity markets.”

The term, unicorn, is generally used to describe privately held companies with a market valuation of $1 billion or more.

The growth of these private startups has negatively impacted the public markets. According to Jones, the number of public companies in the U.S. has dropped by half over the past decade.

Jones described the “founder-friendly” financing model for private equity which seems to sum up what has happened in the grotesque WeWork business model. Jones said in her prepared testimony:

“Until recently, startup companies and their founders were subject to tight controls exerted by representatives of the venture capital funds that financed them. Venture capital investors traditionally insisted on board seats, had the power to veto major decisions, and through a strategy of staged investments exercised final control over whether or not a company survived. Under this governance model, founders were vulnerable to being replaced by professional managers with a track record of leading publicly traded firms. Investor control also meant founders faced intense pressure to prove their concept and profitability, so they could proceed along the pipeline toward an eventual IPO…

“Beginning around 2010, the tables turned as startup founders began to gain the upper hand. As venture capitalists competed for access to deals with sovereign wealth funds and mutual funds, they began to offer financing on ‘founder-friendly’ terms. In the founder-friendly model, founders receive shares with super voting power (typically ten votes per share), which enables founders to maintain control over the board of directors, despite having relatively small financial stake in the firm.

“When founders control the board, an important source of discipline over the startup’s operations is neutralized. The venture capitalists who once called the shots can now be outvoted by the founder and his allies on the board. This new era of founder control has created an environment at unicorns that is ripe for management abuse.”

That would seem to perfectly describe what happened at WeWork. The dumb-tourist type of board allowed WeWork’s founder and CEO, Adam Neumann, to buy commercial buildings and then lease them to WeWork. According to the prospectus for the IPO, the company owes Neumann “future undiscounted minimum lease payments” of “approximately $236.6 million….”

After 9 years in business, WeWork has never made a dime of profits and its losses are escalating. It lost $900 million in the first half of this year alone. Under the terms of the WeWork prospectus, the retail investor would be more of a spectator rather than a shareholder. The prospectus explains:

“Adam [Neumann] controls a majority of the Company’s voting power, principally as a result of his beneficial ownership of our high-vote stock. Since our high-vote stock carries twenty votes per share, Adam will have the ability to control the outcome of matters submitted to the Company’s stockholders for approval, including the election of the Company’s directors. As a founder-led company, we believe that this voting structure aligns our interests in creating shareholder value.”

U.S. markets once commanded the respect and trust of the world. Today, U.S. markets are simply a well-orchestrated wealth transfer mechanism for the one percent.