By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: August 7, 2014

The U.S. Senate has been holding hearings since June which show a clear rethinking on what type of legislation it must enact going forward to achieve meaningful reforms of Wall Street and protect the economy from its excesses.

The 849-page Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation, enacted four years ago in 2010, mandated 398 new rules; just 208 of those rules, or 52 percent, have been enacted and none of them seem to be reining in excesses on Wall Street.

To understand why Dodd-Frank has been such a failure in reforming Wall Street conduct, one need only read the following sentence and think about it for a moment:

The above sentence refers to the 37-page legislation put in place in 1933 after Congress had thoroughly investigated the causes of the 1929-1932 stock market crash that set off the Great Depression and found the core cause to have been Wall Street investment banks having access to savers’ bank deposits to make wild speculative gambles in securities. This legislation is known today as the Glass-Steagall Act, named after Senator Carter Glass and House Rep Henry Steagall who led the effort to pass the legislation.

Dodd-Frank, which was addressing the exact same type of market crash, the abuse of depositors’ funds, and the biggest economic downturn since the Great Depression, did just the opposite of the Glass-Steagall Act. It allowed the abusive Wall Street banks to hold even greater amounts of insured deposits and to become ever more creative in how they abused those deposits.

The Glass-Steagall legislation did exactly what it said it would do: it provided “safer and more effective use of the assets of banks” by barring Wall Street investment banks from accepting deposits or being affiliated with banks accepting deposits. It prevented the “undue diversion of funds into speculative operations” by banning banks holding deposits from underwriting securities.

The 1933 Congress understood that the business of banking is to make sound loans to viable businesses to grow U.S. industry and create good jobs that underpin a sound economy. Gambling in stocks, and futures and exotic, hard to price derivatives should never be an authorized use of bank depositor funds – which are backstopped by the U.S. taxpayer.

The Glass-Steagall Act served this country incredibly well for 66 years until Wall Street lobbyists finally forced its repeal in 1999. It worked because of its simplicity – and its threat of five years of jail time for those who violated its key provisions.

A sizeable portion of its 37 pages dealt with the establishment of insurance on bank deposits, what we know today as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation or FDIC. The insurance guarantee had to be put in place in 1933 because the public had lost confidence in holding their deposits in banks.

The provisions banning deposit-taking banks from being engaged in the securities business, Sections 16, 20 and 21, are elegant in their simplicity. There are no 398 rules to be studied and debated for years before enactment. The key provisions of the following three sections all took effect one year after the enactment of the legislation in 1933.

Section 16 said that “The business of dealing in investment securities by the [banking] association shall be limited to purchasing and selling such securities without recourse, solely upon the order, and for the account of, customers, and in no case for its own account, and the association shall not underwrite any issue of securities.”

Section 20 mandated that “After one year from the date of the enactment of this Act, no member bank shall be affiliated in any manner described in section 2 (b) hereof with any corporation, association, business trust, or other similar organization engaged principally in the issue, flotation, underwriting, public sale, or distribution at wholesale or retail or through syndicate participation of stocks, bonds, debentures, notes, or other securities.”

Section 21 reaffirmed the provisions of Sections 16 and 20, noting: “(a) After the expiration of one year after the date of enactment of this Act it shall be unlawful— (1 ) For any person, firm, corporation, association, business trust, or other similar organization, engaged in the business of issuing, underwriting, selling, or distributing, at wholesale or retail, or through syndicate participation, stocks, bonds, debentures, notes, or other securities, to engage at the same time to any extent whatever in the business of receiving deposits subject to check or to repayment upon presentation of a passbook, certificate of deposit, or other evidence of debt, or upon request of the depositor.”

And Section 21 added jail time for violators, mandating that anyone violating the provisions of that section would, upon conviction, “be fined not more than $5,000 or imprisoned not more than five years, or both.”

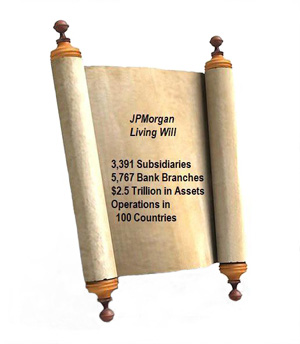

Watching closely each of the hearings held in the Senate on the topic of Wall Street in June and July of this year, together with the game-changing March 15, 2013 hearing on Wall Street’s largest bank, JPMorgan Chase, which has $2.5 trillion in assets, 3,391 subsidiaries, 5,767 bank branches, and operates in 100 countries, it’s clear that the U.S. Senate has figured out it was played for a fool in approving the Dodd-Frank-chase-your-tail-in-circles-for-years legislation.

Both Democrats and Republicans have opened their eyes. In his opening remarks at the March 15, 2013 hearing of JPMorgan Chase’s infamous London Whale hearing, Senator John McCain said:

“This investigation into the so-called ‘Whale Trades’ at JPMorgan has revealed startling failures at an institution that touts itself as an expert in risk management and prides itself on its ‘fortress balance sheet.’ The investigation has also shed light on the complex and volatile world of synthetic credit derivatives. In a matter of months, JPMorgan was able to vastly increase its exposure to risk while dodging oversight by federal regulators. The trades ultimately cost the bank billions of dollars and its shareholders value.

“These losses came to light not because of admirable risk management strategies at JPMorgan or because of effective oversight by diligent regulators. Instead, these losses came to light because they were so damaging that they shook the market, and so damning that they caught the attention of the press. Following the revelation that these huge trades were coming from JPMorgan’s London Office, the bank’s losses continued to grow. By the end of the year, the total losses stood at a staggering $6.2 billion dollars.”

The funds that JPMorgan had gambled with, it was forced to admit, belonged to its bank depositors. They were not gambling with their own capital. And this was 2012, two years after the passage of Dodd-Frank that was supposed to reform Wall Street. How did the losses come to light? Were it not for reporters at Bloomberg News and the Wall Street Journal, who were tipped off by hedge funds that were being whipsawed in the market by JPMorgan’s outsized bets, the losses might not have come to light until it was too late. The initial response from the traders involved was to disguise the extent of the losses while making more trades in an effort to get whole, thus we will never really know if this gamble could have imperiled the bank had it not been caught by intrepid reporters.

On July 31, the U.S. Senate took testimony from Edward J. Kane, Professor of Finance at Boston College, who provided persuasive testimony that the implied future bailouts by the government of these large Wall Street banks is creating market distortions that favor the biggest banks. Kane testified:

“Being TBTF [too-big-to-fail] lowers both the cost of debt and the cost of equity. This is because TBTF guarantees lower the risk that flows through to the holders of both kinds of contracts. The lower discount rate on TBTF equity means that, period by period, a TBTF institution’s incremental reduction in interest payments on outstanding bonds, deposits, and repos is only part of the subsidy its stockholders enjoy. The other part is the increase in its stock price that comes from having investors discount all of the firm’s current and future cash flows at an artificially low risk-adjusted cost of equity. This intangible benefit generates capital gains for stockholders and shows up in the ratio of TBTF firms’ stock price to book value.”

Kane then set off alarm bells with this warning: “The warranted rate of return on the stock of deeply undercapitalized firms like Citi and B of A [Bank of America] would have been sky high and their stock would have been declared worthless long ago if market participants were not convinced that authorities are afraid to force them to resolve their weaknesses.”

Senator Sherrod Brown chaired another hearing on July 16, titled “What Makes a Bank Systemically Important.” It was the unanimous opinion of this hearing panel that forcing a regional bank engaging in safe and sound banking and lending practices with $50 billion in assets to undergo stress tests and other regulatory rigors as a systemically important financial institution placed in the same league as a $2.5 trillion bank like JPMorgan, is nonsense. And yet, that is what is going on.

During Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s “Semiannual Monetary Policy Report” to the Senate on July 15, Senator Elizabeth Warren questioned Yellen on progress in ensuring that Wall Street’s behemoths had a credible plan for winding-down if they got into trouble. Warren compared the situation of Lehman Brothers at the time of its collapse in September 2008 to the size of JPMorgan today. Lehman, said Warren, had $639 billion in assets and 209 subsidiaries when it failed and it took three years to unwind the bank. Today, said Warren, JPMorgan has $2.5 trillion in assets and a staggering 3,391 subsidiaries. (The collapse of the much smaller Lehman and its interconnectedness with other Wall Street banks is largely blamed for setting off the panic on Wall Street. The largest Wall Street banks remain highly interconnected today.)

Warren pointedly asked Yellen if these big Wall Street banks had ever given the Fed wind-down plans that were “credible.” Yellen failed to answer the question directly, calling it a “process,” and adding that some of the wind-down plans, so-called living wills, encompass “tens of thousands of pages.”

Less than three weeks after Senator Warren questioned if the wind-down plans were credible, the FDIC announced this week that the largest banks on Wall Street did not have credible plans and sent them back to the drawing board – four years after Dodd-Frank was enacted.

In both June and July, the Senate took testimony on what Wall Street has been doing with depositor money instead of making sound loans to sound businesses. It hasn’t been pretty. To a very large degree, Wall Street firms are trading stocks in their own unregulated stock exchanges called dark pools, or they’re lending vast sums of money to hedge funds for wild gambles, or they’re making loans to highly leveraged companies to become more highly-leveraged by buying out other companies – which will likely mean lots of job cuts rather than job creation along with piles of junk debt.

At a June 17 hearing titled “Conflicts of Interest, Investor Loss of Confidence, and High Speed Trading in U.S. Stock Markets,” Senator Carl Levin had this to say:

“We are in the era of high-speed trading. I am troubled, as are many, by some of its hallmarks. It is an era of market instability, as we saw in the 2010 ‘flash crash,’ which this Subcommittee and the Senate Banking Committee explored in a joint hearing, and in several market disruptions since. It’s an era in which stock market players buy the right to locate their trading computers closer and closer to the computers of stock exchanges – conferring a miniscule speed advantage yielding massive profits. It’s an era in which millions of trade orders are placed, and then canceled, in a single second, raising the question of whether much of what we call the market is, in fact, an illusion.”

How much more will it take before Congress admits that it has to separate deposit-taking banks from the casinos on Wall Street. The fate of a nation and the hopes and dreams of its children and its young, jobless graduates, hang in the balance.