By Pam Martens: June 11, 2014

Wall Street On Parade has been reporting for some time now that much of Wall Street’s past and current history has up and disappeared – either at the hands of high speed shredders on orders from the SEC, or through Courts sealing documents, or Wall Street’s private justice system preventing access to hearings, non-disparagement contracts when you change your job on Wall Street, or critical pieces of Wall Street history just go missing and no one can find out exactly why. Now we learn that a vital book on Wall Street’s history had vanished until an NYU Professor made it his mission to return it to the public’s hands.

In 2011, Darcy Flynn, an SEC lawyer, told Congressional investigators and the SEC Inspector General that for at least 18 years, the SEC had been shredding documents and emails related to its investigations — documents that it was required under law to keep. Flynn explained to investigators that by purging these files, it impaired the SEC’s ability to see the connections between related frauds on Wall Street.

In 2010, we reported at CounterPunch that not only was it next to impossible to find on line the original text of the historic Glass-Steagall Act which had protected the U.S. economy from the ravages of Wall Street’s recklessness for seven decades until its repeal in 1999, but the National Archives wanted to charge me $1505 to obtain a copy of this public legislation. After much sleuthing, we obtained a copy from the St. Louis Fed and made it available to the Internet Archive which has kindly kept it alive on its web site.

In March of this year we reported that former Fed Chairman, Ben Bernanke, will not turn over the details of who he met with and why on 84 occasions during the height of the financial crisis in 2007 and 2008. The information is sealed.

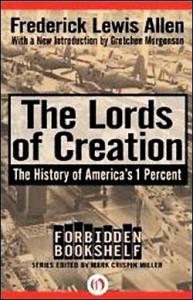

Now, in his quest to return disappeared books to inquiring minds, NYU Media Studies Professor, Mark Crispin Miller, has stumbled upon a potential landmine for Wall Street. In conjunction with Open Road Media, Miller has unearthed and is bringing back to life important vanished books under the imprint “Forbidden Bookshelf.” One of those books is The Lords of Creation: The History of America’s 1 Percent by Frederick Lewis Allen.

The only thing to change about the book is a new forward by Miller and an introduction by business writer, Gretchen Morgenson, of the New York Times. And, of course, that second half of the title has been added. In 1935 when the book was originally published, Wall Streeters were still called banksters. We can thank Occupy Wall Street for successfully marketing the 1 percent brand.

We asked Miller to explain why this book was selected. His response:

“The Lords of Creation is a brilliant early history of the plutocratic fix we’re in today; and so, rather than slip out of print, it should have been a steady seller all these years — required reading in our schools, and maybe even dramatized on PBS.

“That that book disappeared, while Allen’s other, lighter histories are still in print, relates to what we might call the financial takeover of American culture since the Sixties.”

Allen is not exactly Edward Snowden or Glenn Greenwald. Allen worked on the editorial staffs of the Atlantic Monthly and Century magazines and was Editor in Chief of Harper’s magazine from 1941 until his death in 1954.

What makes the disappearance of The Lords of Creation particularly suspicious is that Allen was born in 1890. That made him 17 years old at the time of the 1907 Bankers’ Panic on Wall Street, when reckless speculation led to bank runs and bankruptcies across America. Allen tells us that the New York Times described the event as “an exhibition of the use of vast power for private ends unrestrained by any sense of public responsibility,” and said the men on Wall Street behaved ‘like cowboys on a spree…shooting wildly at each other in entire disregard of the safety of the bystanders.”

Allen was 22 years old when the House of Representatives formed the Pujo Committee hearings to investigate the concentration of wealth and power in unclean hands on Wall Street; and Allen was 39 years old when Wall Street had its worst crash in its history in 1929 and ushered in the Great Depression.

Allen was 22 years old when the House of Representatives formed the Pujo Committee hearings to investigate the concentration of wealth and power in unclean hands on Wall Street; and Allen was 39 years old when Wall Street had its worst crash in its history in 1929 and ushered in the Great Depression.

Allen’s book is dangerous because he had a front row seat and thus could personally document the calamitous crashes that Wall Street bestowed on the country before the passage of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933, which barred banks holding insured deposits from owning or affiliating with firms that underwrote or traded securities, removing the possibility of bank runs and the looting of small savers’ money.

Allen gives a detailed accounting of each of these eras and the Wall Street men who ruled the Street. One quickly realizes that the very same hubris and approaching dangers exist today, just the names have changed. John Pierpont Morgan of the House of Morgan stands in today in the flesh of Jamie Dimon, Chairman and CEO of the successor firm, now called JPMorgan Chase. Last year JPMorgan paid a fine of $920 million for using hundreds of billions of dollars in bank deposits to gamble in high risk derivatives. It lost at least $6.2 billion in this speculative binge. Its bank regulator, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, said the bank had engaged in “recklessly unsafe and unsound practices” which were “part of a pattern of misconduct.”

The powerful Charles Mitchell of National City Bank (now Citigroup) detailed in Allen’s book had a modern era equivalent in Sanford (Sandy) Weill who sucked close to $1 billion in compensation from the bank and then walked away two years before the bank crashed into the arms of the taxpayer.

Allen’s book becomes even more dangerous to Wall Street in pointing out that it was the fact that these high-risk, Wall Street stock speculators were also allowed to own banks and hold bank deposits that made each crash so debilitating to the general economy. The book maps out a ringing endorsement and siren call for restoring the Glass-Steagall Act immediately. In July of last year, Senator Elizabeth Warren dropped the bombshell in the Senate that she was introducing bipartisan legislation to do just that.

Equally important, the book’s exquisite detailing of the unending hubris and calamitous crashes of these Wall Street titans of yesteryear before the passage of the Glass-Steagall Act annihilates the preposterous platform unleashed on a naïve, financial-history-deprived nation by former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan who helped push through the deregulation of Wall Street in the late 90s and early 2000s. That flaky theory, completely debunked by historical fact when you can find it, was that upstanding men on Wall Street would look out for the good of the country because it was in their own interests to do so. After the economy crashed at the hands of these greed-obsessed men in the Great Recession, Greenspan offered a scarred nation these words of apology: “I got it wrong.”

Another inconvenient truth that today’s corporate suite might wish to bury along with this book is Allen’s inclusion of the theory behind Henry Ford more than doubling most workers’ wages in 1914 at the Ford Motor Company by boosting pay to $5 a day to reduce employee turnover and build productivity. Allen tells us: “The answer which Ford gave was of course familiar in economic theory and in the oratory of men like Schwab, but not in practice. It was that the benefits of increased efficiency must be deliberately passed on to the consumers – and that the employer’s own workmen are consumers.”

As corporations and conservatives attempt to beat back an increase in minimum wage, this is not a theory to which one wants to draw attention – especially with Robert Reich out on the stump with his documentary showing that in both 1928 and 2007 – the years before the two greatest Wall Street crashes in history – income inequality in the U.S. reached new peaks.