By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: January 18, 2018

Photo of the Trading Floor at the New York Fed (Obtained by Wall Street On Parade from an Educational Video Despite Stonewalling by the New York Fed)

To understand how the U.S. central bank, known as the Federal Reserve, is influencing the froth of the stock market, you need to take a few moments to understand the interaction of bond yields with stock prices. Sophisticated investors who predominate in the markets compare the yield on bonds to the cash dividend yield on stocks to determine which is a better value. Following the financial crash of 2008, the Federal Reserve began buying up Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed bonds in the marketplace to the overall tune of more than $3 trillion. This has driven down bond yields and provided an artificial boost to the stock market.

The Fed’s assets swelled from $914.8 billion at the end of 2007 to $4.5 trillion in 2014 from its bond buying program. In just the single year of 2013 the Fed’s assets mushroomed by a staggering $1 trillion — from $2.9 trillion at the end of 2012 to $4 trillion at the end of 2013, according to the audited financial statement of the Fed’s books. As of October 25, 2017, its assets remain in the $4.5 trillion arena, at $4.461 trillion.

The Fed’s active involvement in messing with the stock market as a fair stock pricing mechanism through its massive purchases of bonds was quaintly called Quantitative Easing (QE) and the public was treated to three doses of it: QE1, QE2 and QE3.

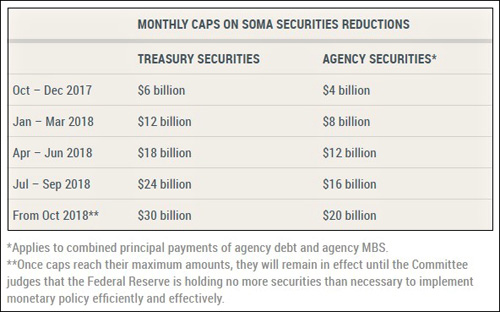

Since 2011, the Fed has been jawboning about how it was going to normalize its balance sheet back to something resembling pre-crisis days. It actually began to cut back its bond purchases by shrinking the amount of its maturing bonds that it will roll over into new bond purchases in October of 2017. But its scheduled cuts are so small and gradual that we are not seeing any material shrinkage in its assets.

During Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s September 17, 2014 press conference, in response to a question from Ylan Mui of the Washington Post, Yellen said: “If we were only to shrink our balance sheet by ceasing reinvestments, it would probably take—to get back to levels of reserve balances that we had before the crisis—I’m not sure we will go that low, but we’ve said that we will try to shrink our balance sheet to the lowest levels consistent with the efficient and effective implementation of policy—it could take to the end of the decade to achieve those levels.”

In 2014, the end of the decade would have been 2020. It’s now 2018 and we’re looking at another half decade before the Fed’s balance sheet would normalize under the current schedule. That’s a very, very long time to provide spiked punch to a tipsy stock market.

The Goldman Sachs overlords who have so thoroughly infused themselves into the Donald Trump administration (the Presidential candidate who promised a draining of the Washington swamp) have figured out a way to get another round of cheap money. Instead of calling it QE4 and getting it from the Fed, it’s being called a corporate tax cut and its coming from the American public who will be squeezed in other areas to pay for it. Jamie Dimon, the Chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase, quickly recognized it for what it was, stating “think of it as a QE4” at an Axios event in Ann Arbor, Michigan in December.

Republicans have been peddling the tax cut as a boon to the economy. That’s not what’s going to happen. U.S. corporations and, particularly, the biggest Wall Street banks are going to use the extra money to continue buying back their own company’s stock, boosting the bank CEOs’ own stock options and enriching their shareholders to the detriment of business and job creation.

On July 31 of last year, Thomas Hoenig, the Vice Chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), sent a stunning letter to the Chair and Ranking Member of the U.S. Senate Banking Committee. Hoenig explained that the 10 largest banks in the country “will distribute, in aggregate, 99 percent of their net income on an annualized basis,” by paying out dividends to shareholders and buying back excessive amounts of their own stock. If those 10 banks had retained a larger share of the earnings they earmarked for dividends and share buybacks in 2017, said Hoenig, they would have been able “to increase loans by more than $1 trillion, which is greater than 5 percent of annual U.S. GDP.”

Hoenig included a chart showing payouts on a bank-by-bank basis. Highlighted in yellow on Hoenig’s chart is the fact that four of the big Wall Street banks are set to pay out more than 100 percent of earnings: Citigroup 127 percent; Bank of New York Mellon 108 percent; JPMorgan Chase 107 percent and Morgan Stanley 103 percent.

Hoenig adds that if just the share buybacks were retained by the banks instead of being paid out, the banks could “increase small business loans by three quarters of a trillion dollars or mortgage loans by almost one and a half trillion dollars.”

Stock buybacks also perform another magic trick for Wall Street bank CEOs like Jamie Dimon whose compensation is based on overall performance. By shrinking the number of shares outstanding through buybacks, it makes the bank’s per share earnings look more robust because they are spread over a smaller number of shares.

According to JPMorgan Chase’s 2017 proxy statement, “Based on Mr. Dimon’s performance, the Board increased his annual compensation to $28 million [in 2016] (from $27 million in 2015).” Notably, according to the proxy, the portion of Dimon’s compensation that was in stock awards was $20.5 million for 2015 and $21.5 million for 2016. Thus, Wall Street CEOs are highly incentivized to keep those stock prices aloft.