By Pam Martens: January 12, 2015

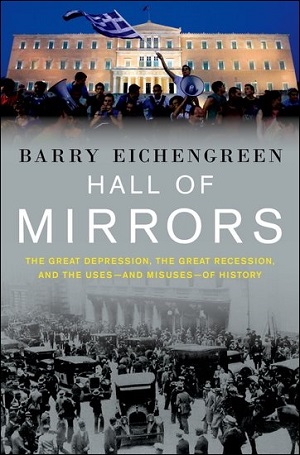

Barry Eichengreen, Professor of Economics and Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley, has written an essential tome contrasting the Great Depression of the 1930s with the Great Recession that began in late 2007 and deepened with the collapse of iconic Wall Street firms in 2008. Aptly titled Hall of Mirrors: The Great Depression, the Great Recession, and the Uses and Misuses of History, the book walks us through ongoing events in the U.S. and Europe during both periods.

Barry Eichengreen, Professor of Economics and Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley, has written an essential tome contrasting the Great Depression of the 1930s with the Great Recession that began in late 2007 and deepened with the collapse of iconic Wall Street firms in 2008. Aptly titled Hall of Mirrors: The Great Depression, the Great Recession, and the Uses and Misuses of History, the book walks us through ongoing events in the U.S. and Europe during both periods.

Professor Eichengreen’s book is well worth reading for the mining of nuggets such as this: “Between 1933 and 1937, real GDP in the United States grew at an annual rate of 8 percent, even though government did only passably well at these tasks. Between 2010 and 2013, by comparison, GDP growth averaged just 2 percent.”

In just two sentences the Professor has encapsulated the timidity of the fiscal response to the crisis and why the word “deflation” is now, six years after the peak of the crisis, gathering steam in headlines.

Amazon.com has the book listed as the number 1 bestseller in public policy. The book is published by Oxford University Press, which wants you to know that it’s a department at the University of Oxford, furthering the University’s “objective of excellence in research…” Professor Eichengreen thanks no less than 39 academics whom he consulted on the manuscript or were helpful in some other way to his writing.

Sadly, neither Professor Eichengreen nor his fellow academics caught this fatal flaw in the book:

“Lehman was not a commercial bank; it did not take deposits. It was thus possible to imagine that its failure might not precipitate a run on other banks like the runs triggered by Henry Ford’s Guardian Group of banks in 1933.”

Lehman owned two FDIC insured banks. It did take FDIC insured deposits and it massively sold FDIC-insured Certificates of Deposit to moms and pops around the country through other broker-dealers, frequently seducing customers with a little higher yield than its competitors in the brokered-CD market.

The gravitas of the Lehman Lie is that it has now traveled from the pages of the New York Times to the President of the United States to the pen of Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman. The Lehman Lie matters greatly because it is the primary argument against reinstating the Glass-Steagall Act – the only means of saving the country from a repeat of 2008; an eventuality that is edging closer by the day.

When Andrew Ross Sorkin of the New York Times first published the Lehman Lie in May 2012, we wrote to the Public Editor, Managing Editor, Business Editor and Publisher, putting the facts before them. Later, we wrote again to the Public Editor. Not one word of correction has been published in all this time.

This is how Sorkin presented the Lehman Lie and how we countered it in 2012, both in print at Wall Street On Parade and in emails to the editors of the New York Times:

Sorkin writes at the New York Times:

“Let’s look at the facts of the financial crisis in the context of Glass-Steagall.

“The first domino to nearly topple over in the financial crisis was Bear Stearns, an investment bank that had nothing to do with commercial banking. Glass-Steagall would have been irrelevant. Then came Lehman Brothers; it too was an investment bank with no commercial banking business and therefore wouldn’t have been covered by Glass-Steagall either. After them, Merrill Lynch was next — and yep, it too was an investment bank that had nothing to do with Glass-Steagall.

“Next in line was the American International Group, an insurance company that was also unrelated to Glass-Steagall.”

Wall Street On Parade:

“There are four companies mentioned in those five sentences and in every case, the information is spectacularly false. Lehman Brothers owned two FDIC insured banks, Lehman Brothers Bank, FSB and Lehman Brothers Commercial Bank. Together, they held $17.2 billion in assets as of June 30, 2008, 75 days before Lehman went belly up. Lehman Brothers Banks FSB is where Lehman handled its mortgage loan originations. When the FDIC approved the Lehman Brothers Commercial Bank application in 2005, it specifically noted that the FDIC insured bank ‘anticipates acting as a derivatives intermediary, engaged in matched trading of interest rate products, primarily interest rate swaps, as well as forward purchase agreements and options contracts.’

“Merrill Lynch also owned three FDIC insured banks. At an FDIC symposium held at the National Press Club in 2003, Merrill Senior VP, John Qua, explained the banking side of Merrill as follows:

“ ‘Merrill Lynch conducts banking in the United States through two depository institutions – Merrill Lynch Bank USA, a Utah industrial loan corporation; and Merrill Lynch Bank and Trust, a New Jersey state non-member bank. We also own a federal savings bank that offers personal trust services to our clients. And we conduct significant banking activities outside the United States through banks in London, Dublin, Switzerland, and elsewhere. The combined balance sheet of our global banks is approximately $100 billion.’

“Bear Stearns owned Bear Stearns Bank Ireland, which is now part of JPMorgan and called JPMorgan Bank (Dublin) PLC. According to JPMorgan, ‘It is the only EU passported bank in the non-bank chain of JPMorgan and provides the firm with direct access to the European Central Bank repo window. It has also been added to the JPMorgan Jumbo issuance programs to issue structured securities for distribution outside the United States.’

“As for the statement that AIG was ‘an insurance company that was also unrelated to Glass-Steagall,’ one has the initial reaction to cancel one’s subscription to the New York Times. AIG owned, in 2008 at the time of the crisis, the FDIC insured AIG Federal Savings Bank. On June 30, 2008, it held $1 billion in assets. AIG also owned 71 U.S.-based insurance entities and 176 other financial services companies throughout the world, including AIG Financial Products which blew up the whole company selling credit default derivatives. What this has to do with Glass-Steagall is that the same deregulation legislation, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act that gutted Glass-Steagall in 1999, also gutted the 1956 Bank Holding Company Act and allowed insurance companies and securities firms to be housed under the same umbrella in financial holding companies.

“AIG’s annuities are owned by moms and pops all over this country and around the world. In many cases, they represent a significant source of income to retirees. Had AIG been allowed to fail, state guaranty funds for insurance products could have been wiped out and the taint of buying insurance products would have damaged legitimate businesses for a lifetime.

“For ongoing evidence as to why insured deposit banks cannot be under the same roof with speculating Wall Street firms, one need only look at what the largest banks in the U.S. are holding today. According to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency which oversees national banks, as of December 31, 2011, inside the insured banks – not their broker-dealer components – were the following derivative holdings: $70.1 trillion at JPMorgan Chase; $52.1 trillion at Citibank; $50.1 trillion at Bank of America; $44.2 trillion at Goldman Sachs Bank USA.”

Barry Eichengreen, Professor of Economics and Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley

The Lehman Lie matters more than ever today because Citigroup has just gotten away with slipping language into the $1.1 trillion spending bill, allowing Wall Street mega banks like itself to hold their trillions of dollars in dangerous derivatives at their FDIC-insured bank.

Let us hope that Professor Eichengreen will have more integrity about the matter than the New York Times and issue a prominently placed correction and clarification. Hall of Mirrors is too important a book to be saddled with Andrew Ross Sorkin’s lie.