By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: August 20, 2024 ~

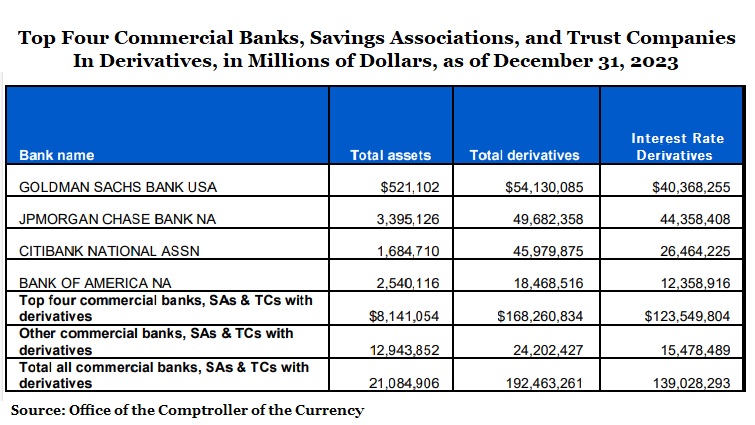

As indicated on the above graph, as of December 31, 2023, Goldman Sachs Bank USA, JPMorgan Chase Bank N.A., Citigroup’s Citibank and Bank of America held a staggering total of $168.26 trillion in derivatives out of a total of $192.46 trillion at all federally-insured U.S. banks, savings associations and trust companies. That’s just four banks holding 87 percent of all derivatives at all 4,587 federally-insured financial institutions in the U.S. that existed as of December 31, 2023.

As indicated on the above graph, as of December 31, 2023, Goldman Sachs Bank USA, JPMorgan Chase Bank N.A., Citigroup’s Citibank and Bank of America held a staggering total of $168.26 trillion in derivatives out of a total of $192.46 trillion at all federally-insured U.S. banks, savings associations and trust companies. That’s just four banks holding 87 percent of all derivatives at all 4,587 federally-insured financial institutions in the U.S. that existed as of December 31, 2023.

You might be asking yourself the very valid question as to why the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010, that followed the Wall Street financial quake of 2008, didn’t correct the derivatives gambling that played a central role in crashing the U.S. financial system. For why the threat of derivatives never actually went away, see our report: Meet the Two Congressmen Who Facilitated Today’s Derivatives Nightmare at Wall Street’s Mega Banks.

As one example of the insane level of leverage concentrated in a handful of megabanks, look at the entry in the above chart for Goldman Sachs Bank USA. That federally-insured bank, part of the international trading conglomerate known as Goldman Sachs Group, is allowed by its federal regulators to have $521 billion in assets but $54 trillion in derivatives.

But don’t worry. Under U.S. accounting rules, these derivatives can be whittled down under the magic known as “netting,” and conveniently moved out-of-sight/out-of-mind off the balance sheet.

When the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission released their final forensic report on the causes of the 2007 to 2010 financial collapse – the worst crisis since the 1929-1932 collapse and Great Depression that followed – it pointed to hidden leverage in off-balance sheet entities at the megabanks on Wall Street as a key driver of the crisis. It wrote:

“From 2000 to 2007, large banks and thrifts generally had $16 to $22 in assets for each dollar of capital, for leverage ratios between 16:1 and 22:1. For some banks, leverage remained roughly constant. JP Morgan’s reported leverage was between 20:1 and 22:1. Wells Fargo’s generally ranged between 16:1 and 17:1. Other banks upped their leverage. Bank of America’s rose from 18:1 in 2000 to 27:1 in 2007. Citigroup’s increased from 18:1 to 22:1, then shot up to 32:1 by the end of 2007, when Citi brought off-balance sheet assets onto the balance sheet. More than other banks, Citigroup held assets off of its balance sheet, in part to hold down capital requirements. In 2007, even after bringing $80 billion worth of assets on balance sheet, substantial assets remained off. If those had been included, leverage in 2007 would have been 48:1, or about 53% higher. In comparison, at Wells Fargo and Bank of America, including off-balance-sheet assets would have raised the 2007 leverage ratios 17% and 28%, respectively.”

Citigroup, of course, blew itself up in 2008 and received the largest bailouts in global banking history. By March of 2009, its stock was trading at 99 cents. By July 2010, it had received $2.5 trillion in secret revolving loans from the Fed over the span of 2-1/2 years, according to the 2011 audit of the Fed’s emergency bailout programs that was released by the Government Accountability Office.

Today, JPMorgan Chase is creating unfathomable risk transfer vehicles and placing them off its balance sheet. What could possibly go wrong?

In January, Anat Admati, Professor of Finance and Economics at Stanford Graduate School of Business, and German economist Martin Hellwig, released an updated and expanded version of their 2013 book The Bankers’ New Clothes: What’s Wrong with Banking and What to Do about It. In it, the authors write:

“Some of the risks that make JPMorgan Chase dangerous cannot actually be seen by looking at its balance sheet because the positions that give rise to them are not included there. These are risks from business units that JPMorgan Chase might own in part or that it sponsors, and to which it has provided guarantees to serve as a backstop if they should have funding problems. These units might be full-flown subsidiaries, or they might be mere ‘letterhead firms,’ vehicles without any drivers, that are established for legal or tax reasons only. The bank’s commitments to these units amount to almost a trillion dollars, but these potential liabilities of the bank are left off the bank’s balance sheet. Yet they are quite relevant to the financial health of JPMorgan Chase.”

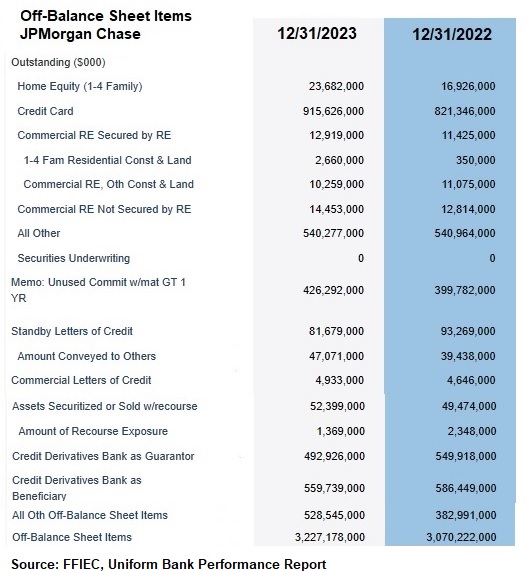

According to financial data at the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), as of December 31, 2023, JPMorgan Chase held $3.227 trillion off-balance sheet.

In JPMorgan Chase’s 10-K public filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission for the period ending December 31, 2023, it reported total assets on its balance sheet of $3.875 trillion. (See page 46 at this link.) That’s versus the FFIEC data showing it has another $3.227 trillion off-balance sheet.

The chart below shows the stunning breakdown of the $3.2 trillion JPMorgan Chase is holding off-balance sheet according to data at the FFIEC. (See this link; check the box “Off-Balance Sheet Items,” then click the hyperlink for “Off-Balance Sheet Items.”)

JPMorgan Chase’s off-balance sheet hubris goes a long way in explaining why the bank’s federal regulators are demanding that it increase its capital by 25 percent. The bank’s response to that was to go on the offensive through its lobbying groups and threaten to sue its federal bank regulators. On Saturday, Bloomberg News reported that Dimon and other megabank CEOs had huddled in private with Jerome Powell, Chair of the Federal Reserve, on July 19 in an effort to weaken the proposed increases in the capital rule.

Because Wall Street megabanks have honed to perfection a century-old bag of tricks that enable them to get their way by intimidating their regulators, game accounting rules with impunity, and put personal greed above the good of the country – the only means of restoring sanity and stability to the U.S. financial system is for Congress to restore the Glass-Steagall Act, which would permanently separate federally-insured banks from the trading casinos on Wall Street.

The seminal book on the critical and urgent need to restore the Glass-Steagall Act is Taming the Megabanks: Why We Need a New Glass-Steagall Act, by Arthur E. Wilmarth. Engaged and concerned Americans owe it to themselves and their families to read this book, understand how the U.S. financial system has morphed into an institutionalized wealth-transfer system, moving wealth from the middle class to the pockets of the denizens of Wall Street. (See, for example, PBS Drops Another Bombshell: Wall Street Is Gobbling Up Two-Thirds of Your 401(k).)