By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: April 23, 2024 ~

Last Friday, the Federal Reserve released its semi-annual Financial Stability Report. In the prior five years, the spring edition of the Fed’s Financial Stability Report was released in May. This year, for reasons we can only guess at (nervously), the Fed released the spring edition early, in April.

Given that last spring the second, third and fourth largest bank failures in U.S. history occurred, handing over $30 billion in losses to the federal Deposit Insurance Fund, and one of those banks (Silicon Valley Bank) experienced the fastest run on its deposits in U.S. history, one particular item in the new report that caught our attention was this:

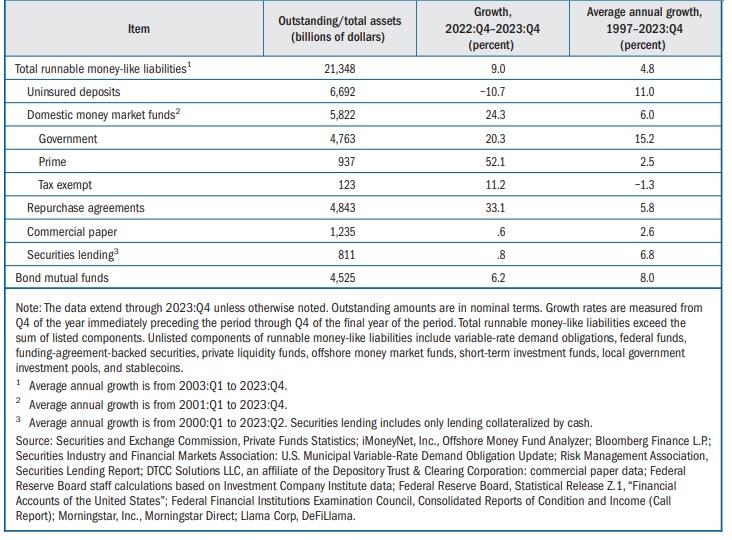

“Overall, estimated runnable money-like financial liabilities grew 8.8 percent to $21.3 trillion (75 percent of nominal GDP) over the past year, as a decline in uninsured deposits was more than offset by an increase in assets under management at MMFs [Money Market Mutual Funds]. As a share of GDP, runnable liabilities remained above their historical median.”

To our way of thinking, “runnable” is not a good word to be associated with banking. Americans look to banks for safety and soundness and big, secure vaults. The idea that things can be “running” out of banks like farm animals stampeding through a hole in the fence is not a comforting image. Add $21.3 trillion to that image in a country that is turning bank bailouts into an art form and you realize quickly that the Fed’s Financial Stability Report is little more than an exercise in CYA. It is, after all, the Fed that keeps bailing out these megabanks on Wall Street while ignoring the screaming need to reform them.

The graph the Fed posted below its statement on “runnables” is even more hair-raising. (See below.) It breaks down the components of the $21.3 trillion in runnables.

In simple terms, “runnables” are liabilities that the financial institution must pay on demand by the customer.

Let’s zoom in on the runnable component that the Fed has listed as $6.692 trillion of uninsured deposits. It was uninsured deposits at Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and to a lesser extent, First Republic Bank, that caused depositors to panic and run for the exits last spring. The FDIC insures deposits up to $250,000 per depositor, per bank. If there is negative news about a bank’s financial condition, depositors holding large amounts above the FDIC insurance limit will be the first to stampede toward the exits. In March of 2023, it took only a few negative social media posts to start an avalanche of digital deposit withdrawals at Silicon Valley Bank. In the span of just 24 hours, $42 billion in deposits had exited the bank with another $100 billion queued up to leave the next day – meaning it was possible for a federally-insured bank to lose 85 percent of its deposits in the span of 48 hours in the digital/social media age.

But what the Fed is not telling you in its new Financial Stability Report about these uninsured deposits is that the vast majority of these uninsured deposits are held by a handful of megabanks on Wall Street – the same ones that the Fed bailed out with trillions of dollars in secret loans during and after the Wall Street collapse of 2008. (See The Deposit Insurance Fund Has a Balance of $117 Billion to Protect Deposits at 4,622 Banks. But One of Those Banks Has $1.4 Trillion in Uninsured Deposits.)

In a report by the FDIC in May of last year on options for insurance reform, it reported the following:

“Uninsured deposits are disproportionally concentrated in the largest banks. At year-end 2022, banks in the top 1 percent of the asset size distribution held about 72 percent of deposits in domestic offices but about 77 percent of uninsured deposits in domestic offices….”

Another runnable listed by the Fed on its graph above is $5.8 trillion in Money Market Mutual Funds. These Funds had to be bailed out during the 2008 financial crisis and again during the COVID-19 pandemic. As we reported previously, “…just six Wall Street firms received 72 percent of the $162.9 billion in cumulative loans” made under the Fed’s money market bailout program during the pandemic. Four of those were Wall Street megabanks.