By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: December 14, 2023 ~

Quietly, on December 1, the New York Fed published the following statement on its website: “The Norinchukin Bank, New York Branch, has been added to the list of Standing Repo Facility Counterparties, effective December 1, 2023.”

The Standing Repo Facility (SRF) is a permanent $500 billion bailout facility created by the Federal Reserve and operated by the New York Fed – the private regional Fed bank where multi-trillion dollar Wall Street bank bailouts have become a regular feature of its operations.

Without any action from the U.S. legislative branch (otherwise known as Congress), the Fed has unilaterally decided to become lender of last resort to Wall Street trading houses (whom the Fed prefers to call its “primary dealers”) and deposit-taking banks, including the uninsured New York branches of foreign banks like Norinchukin Bank.

If you have never heard of Norinchukin Bank, don’t feel badly. Neither have we and we’ve been monitoring global banks for decades. According to Norinchukin Bank’s financial statement for its fiscal year ending March 31, 2023, it had $708 billion in assets. If it were a U.S. bank, it would be the fifth largest by assets, just behind JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo and Citibank.

The notice from the New York Fed about adding Norinchukin Bank to its bailout facility grabbed our attention for two reasons. First, it came out on a Friday, which is typically when financial entities dump bad news they hope will disappear over the weekend. And also because the Standing Repo Facility was the successor to the trillions of dollars in still unexplained emergency repo loans the Fed had to pump into Wall Street in the fourth quarter of 2019.

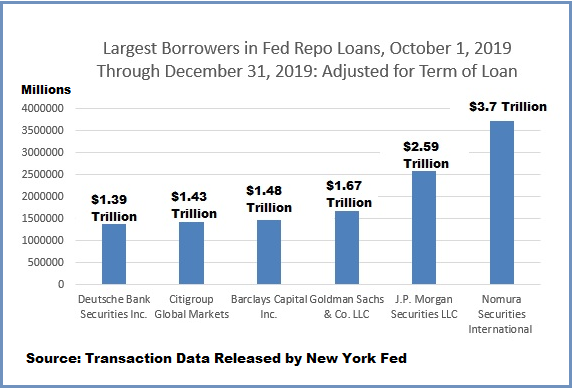

As indicated on the chart below, a unit of another Japanese bank, Nomura, was the largest recipient of Fed bailout largesse in the last quarter of 2019. Nomura borrowed $3.7 trillion cumulatively under the Fed’s emergency repo loan program, topping the amount borrowed by JPMorgan Chase by $1.11 trillion. The loan amounts on the chart come directly from the emergency repo loan data released quarterly by the New York Fed, adjusted for the term of the loan. (Reverse repo amounts have to be deleted from the data released by the Fed.)

The Fed swung into emergency mode on September 17, 2019 when the rate on overnight repo loans suddenly spiked from around 2.25 percent to as high as 10 percent at one point, strongly suggesting that Wall Street banks were backing away from questionable borrowers. The Fed set up its own repo facility to make tens of billions of dollars in loans available to trading houses on Wall Street on a daily basis, and at very cheap interest rates that did not reflect the credit risk of the individual trading houses. (Repos, short for Repurchase Agreements, are a short-term form of borrowing where corporations, banks, brokerage firms and hedge funds secure loans, typically for one day, by providing safe forms of collateral such as Treasury notes.) The Fed hadn’t made these emergency repo loans since the financial crisis of 2008.

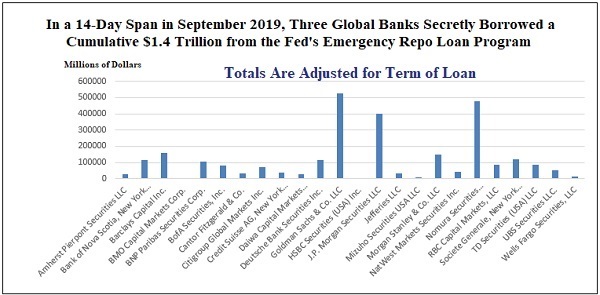

Instead of making just the typical overnight repo loans in 2019, the New York Fed extended some of these repo loans to 14-day, 28-day, and 42-day term loans, further suggesting some banks were in dire need of long-term liquidity.

The distress being experienced by Nomura likely came from its large derivatives exposure. The fact that JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs were, from the get-go, also borrowing heavily from the Fed, suggests that the three firms were counterparties to each other’s derivatives. (See 14-day chart below beginning when the Fed first launched its emergency repo loan bailouts in September 2019.)

Celebrating 100 years of existence this year, Norinchukin Bank describes itself as a wholesome outfit on its website:

“It is a cooperative private financial institution with a clear mission to ‘contribute to the development of the nation’s economy by supporting the advancement of Japan’s agriculture, fishery and forestry industries by providing financial services for the members of the agricultural, fishery and forestry cooperative system.’ ”

Helping the agricultural, fishery and forestry industries in Japan, unfortunately, has somehow morphed into this:

“Under the policy of reinforcing our asset management business, we transferred our credit and alternative investment functions to Norinchukin Zenkyoren Asset Management (NZAM), an affiliated company of the Bank, in fiscal 2021. In addition, we newly established Norinchukin Capital (NCCAP), for private equity investment and Nochu-JAML Investment Advisors (NJIA), for managing domestic real estate private REITs.

“NZAM now offers a full lineup of products according to economic cycles and launched its credit flagship fund in August 2022. NJIA has begun managing a domestic real estate private REIT, in which the Bank also has a stake, offering prime yen-denominated investment opportunities. We will continue to ensure the effective use of our management experience to meet diversified customer needs (including ESG investment products).”

This sounds like some serious mission creep to us. Instead of its “clear mission” to support the “advancement of Japan’s agriculture, fishery and forestry industries,” Norinchukin Bank sounds like it is attempting to remake itself into a cross between Blackstone and Blackrock.

According to its most recent financial statement, Norinchukin Bank does not appear to be heavily involved in derivatives. However, it has been heavily involved in CLOs – Collateralized Loan Obligations, which frequently include high risk debt.

In February of 2020, Reuters reported this: “Norinchukin, the world’s largest CLO investor, ceased its buying in the second half of 2019. Its December holdings were ¥8trn (US$72bn), the same level as in June last year, according to the bank’s latest result released early this month.”

The Fed may have another particular interest in making sure Norinchukin Bank has ample access to liquidity. The bank has typically been a large buyer of U.S. Treasury securities.

In a NikkeiAsia.com interview in March of this year, Norinchukin Bank’s Chief Investment Officer, Hiroshi Yuda, said this:

“We were hit with unrealized losses, largely in U.S. government bonds. We actually started reshuffling our bond holdings in 2021 to prepare for rates to rise, but we rushed to unload in response to the jump in 2022. We sold around 12 trillion yen in securities, mainly U.S. government bonds, in the April-September half. We have continued to sell since October.”

At today’s conversion rate, dumping 12 trillion yen in U.S. government bonds amounts to dumping $84.6 billion. When U.S. government bonds are sold in large quantities, it puts downward pressure on the price of the bond in the secondary trading market, resulting in higher yields. Higher yields, in turn, raise the debt service cost to the U.S. government.

Like mega banks in the U.S., Norinchukin Bank is also grappling with heavy unrealized losses on the government debt securities it has not dumped into the market but is maintaining on its balance sheet. According to its fiscal year-end financial statement linked above, at fiscal year-end (March 31, 2023) it had unrealized losses on investment securities of $20 billion, which netted out to a loss of $10.76 billion after adjustments for reclassification and tax effects.

The bottom line is this: what kind of a Faustian bargain has the Fed ensnarled itself in by becoming the lender of last resort to sprawling trading operations around the globe? And how long will Americans continue to allow the privately-owned New York Fed to usurp power from the elected members of the legislative branch of the United States?

Related Articles: