By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: June 6, 2023 ~

As we reported yesterday, Silicon Valley Bank was not even on the “Problem Bank List” maintained by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) when it imploded in a span of 48 hours in March. According to testimony by the Federal Reserve’s Vice Chairman for Supervision, Michael Barr, on March 28 before the Senate Banking Committee, depositors had yanked $42 billion of their deposits from the bank on March 9 and had queued up to grab another $100 billion on March 10 when it was abruptly put into FDIC receivership. Had the FDIC not stepped in, Silicon Valley Bank would have lost 85 percent of its deposits in a two-day stretch.

Two of the key internal problems at Silicon Valley Bank were its large amount of uninsured deposits (which pose a flight risk in times of banking turmoil) and Silicon Valley Bank’s decision to classify 43 percent of its assets to the Held-to-Maturity (HTM) category. Under a highly controversial accounting rule, HTM debt instruments are not marked to market or shown on the balance sheet at fair value, but are instead listed at amortized cost – effectively what was paid for the debt instrument at the time of its purchase.

The HTM accounting treatment is allowing banks to create an illusion on their balance sheet as to what their assets are worth during the fastest rate increases by the Federal Reserve in 40 years. The bigger the dollar amounts held as HTM investment securities, the bigger the illusion. (While fair value for HTM securities and unrealized losses are provided in supplemental charts in SEC filings, the fair value is not reflected in the asset value on the balance sheet itself – leaving the average shareholder clueless as to what the bank’s assets are actually valued at by the market.)

Because a large portion of the debt instruments held as HTM were purchased with a fixed rate of interest when interest rates were much lower, the current market prices of these debt instruments may have declined anywhere from 10 to 25 percent.

It now turns out that two of the largest federally-insured banks in the U.S. – and potentially others that we have yet to explore – are holding hundreds of billions of dollars of debt securities in the HTM category.

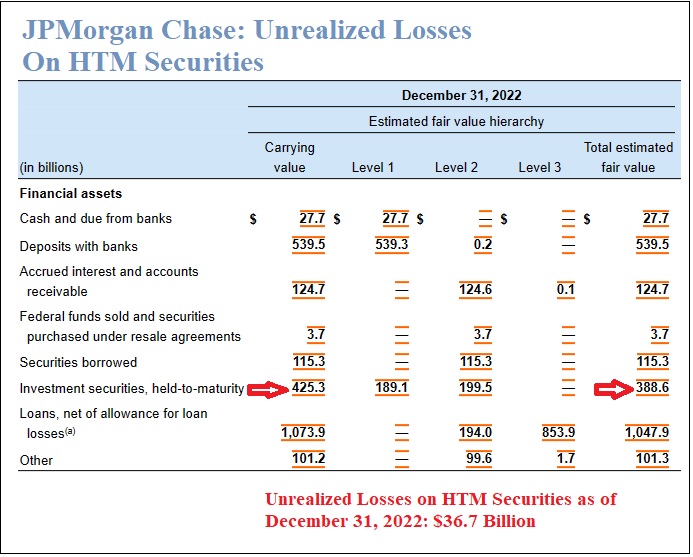

As the charts below from the 2022 10-K (Annual Report) filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission indicate, JPMorgan Chase is holding $425.3 billion in HTM securities, which actually have a fair market value of just $388.6 billion or an unrealized loss of $36.7 billion.

Making the situation even more questionable for JPMorgan Chase, as we reported on May 30, most of these debt instruments were not designated as HTM at time of purchase, but were transferred to that category in 2020, 2021, and 2022. (See our report: JPMorgan Chase Transferred $347 Billion in Debt Securities Over the Last 3 Years to Inflate Its Capital Using a Controversial Maneuver.)

JPMorgan Chase has admitted to five felony counts since 2014, including two for its dicey handling of the business bank account of the biggest Ponzi schemer in U.S. history (Bernie Madoff); and three separate counts for rigging the foreign exchange, precious metals and U.S. Treasury market. (Not to put too fine a point on it, but the U.S. Treasury market is how the United States pays its bills.) The deeply conflicted Board at JPMorgan Chase has kept Jamie Dimon as its Chairman and CEO throughout this crime wave.

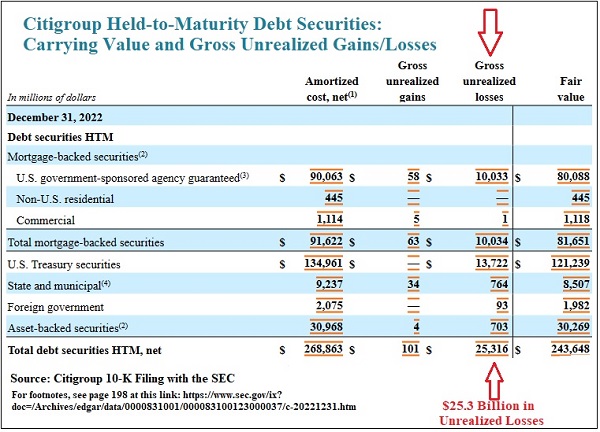

Citigroup’s 10-K for 2022 shows $268.9 billion in HTM securities, which have a fair market value of just $243.6 billion, or an unrealized loss of $25.3 billion.

Citigroup teetered near collapse in 2008; its stock price went to 99 cents in the spring of 2009; and it received over $2.5 trillion in secret, cumulative loans from the Federal Reserve from December 2007 to at least July of 2010 to keep it from total collapse, according to the audit released in 2011 by the Government Accountability Office (GAO). (See page 131 of the GAO report.) For additional insights into the role that accounting played in Citigroup losing almost all of its market value in 2008 and 2009, see accounting expert and Citigroup whistleblower Richard Bowen’s May 15 report.

After the financial crisis of 2008 to 2010 and the exposure of accounting maneuvers that played a role in enabling it, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) attempted to require fair value accounting for most financial instruments. The proposal had wide support but was shot down as a result of heavy pressure from the banking industry.

The CFA Institute, the not-for-profit association of investment professionals that awards the CFA (Certified Financial Analyst) and CIPM (Certificate in Investment Performance Measurement) designations, submitted an exhaustive written response to the FASB’s proposal, including a 29-page Appendix that provided an in-depth analysis of why fair value reporting was necessary for both transparency and the integrity of financial reports.

An argument in the CFA Institute’s letter was as follows:

“Based upon the market experience of our members and the relevant academic research, there is strong evidence that financial institution share prices incorporate the fair value of their financial instruments. The question for standard setters is whether the financial statements should likewise reflect financial instrument values in an attempt to mitigate the economic disconnect between book value and share price. We believe this is important to ensure financial statements are relevant for all investors in making investment decisions. What standard setters need to consider is whether all investors, not just some professional analysts or investors, can perform such analysis and valuation themselves and whether financial statements should assist all users and investors in the determination of the value of the enterprise. Decision-useful financial information such as the fair value of financial instruments, which represent nearly all assets and liabilities of a financial institution, should not bypass the basic financial statements.”

JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup also have exposure to large amounts of uninsured deposits. (See our report: At Year End, 4,127 U.S. Banks Held $7.7 Trillion in Uninsured Deposits; JPMorgan Chase, BofA, Wells Fargo and Citi Accounted for 43 Percent of That.)