By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: May 30, 2023 ~

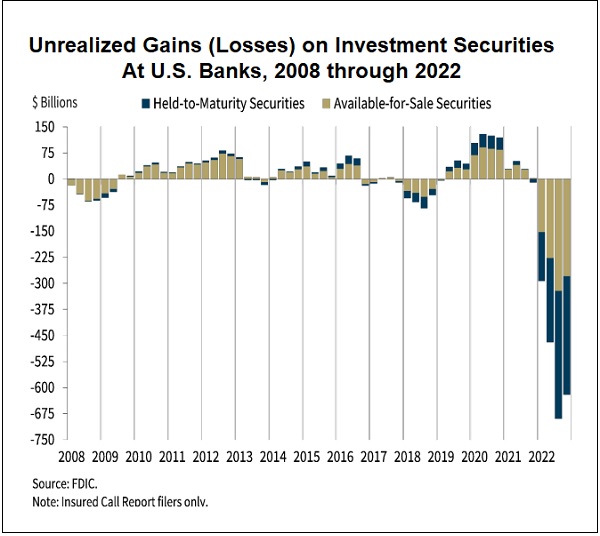

Wall Street mega banks, as well as others, are moving vast amounts of their debt securities from one accounting category to another accounting category in order to stretch out unrealized losses over the life of the instrument. As the FDIC chart above indicates, as of December 31, 2022 unrealized losses on investment securities at U.S. banks stood at more than $600 billion.

According to JPMorgan Chase’s 10-K (Annual Report) filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission, over the past three years it has moved a total of $347 billion (yes, “billion” with a “b”) of investment securities from the accounting category called “Available-for-Sale” (AFS) to the accounting category called “Held-to-Maturity” (HTM).

JPMorgan Chase’s 2022 10-K advises as follows: “During 2022 and 2021, the Firm transferred $78.3 billion and $104.5 billion of investment securities, respectively, from AFS to HTM for capital management purposes.”

JPMorgan Chase’s 2020 10-K adds this: “During 2020, the Firm transferred $164.2 billion of investment securities from AFS to HTM for capital management purposes.”

Add up the three years of transfers and you’re looking at a cool $347 billion that went from one accounting category to another. The reason? JPMorgan refers to its motivation as “capital management.” But let’s take a deeper dive.

The Kansas City Fed explains the difference between AFS and HTM accounting treatment as follows:

“Investment securities are designated on the balance sheet as either ‘held to maturity’ (HTM) or ‘available for sale’ (AFS). As the name suggests, HTM securities are those the bank does not intend to sell but instead expects to hold until they fully mature. AFS securities, on the other hand, are securities that the bank intends to hold for some time but may sell before maturity. HTM securities are reported at amortized cost on the balance sheet, and changes in their market value do not affect total assets or book equity. Instead, the reported value of HTM securities changes as their underlying discount or premium amortizes over time. AFS securities, on the other hand, are reported at market value. Changes in the market value of AFS securities—that is unrealized gains or losses—are reported in book equity as part of the accumulated other comprehensive income (AOCI) account. Therefore, as the market value of AFS securities rises (falls), assets and book equity also rise (fall).”

The Federal Home Loan Bank of Chicago explains the motivation to be shuffling investment securities from AFS to HTM as follows:

“The final option to explore to curb investment portfolio losses, especially in anticipation of yet higher interest rates in the near term, is to transfer AFS securities into the HTM category. In accordance with ASC 320-10-35-10B, an institution is permitted to reclassify and transfer a security to the HTM category at its amortized cost basis, if the entity has positive intent and ability to hold these securities until maturity. Any unrealized loss may be amortized over the remaining life of the security as an adjustment of yield in a manner consistent with the amortization of any purchased premium or discount.” (Italics added.)

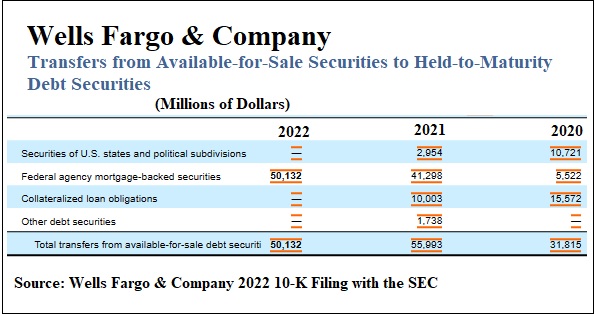

Wells Fargo is a peer bank to JPMorgan Chase. According to a chart included in its 2022 10-K filing with the SEC (see chart below), it transferred $137.94 billion in investment securities, over the same three-year time span, from AFS to HTM. That’s just 40 percent of the amount transferred by JPMorgan Chase.

On March 15, Thomson Reuters ran an article quoting Kurt Gee, Assistant Professor of Accounting at Pennsylvania State University. Gee provided additional insight into how HTM accounting works, stating:

“The way we account for held-to-maturity bonds is based on the original interest rate when the bond was issued, which we call ‘amortized cost’ on the balance sheet.

“And because that bond’s interest rate is fixed and contractually specified, if the real world’s interest rate changes we ignore those changes in accounting and they are not reflected on the balance sheet. So when interest rates have increased dramatically relative to when the bonds were issued, the bonds the bank holds are worth less to potential buyers. And if the bank suddenly needs capital to be able to repay depositors and they have to sell those bonds, the price they sell them at will be less than the price recorded on the balance sheet. That can be a problem when there’s a liquidity issue and banks need to access funds, because they’re going to have to sell at a much lower price than investors think they’re worth based on the balance sheet.”

CPA/CFA Sandy Peters posted the following at the CFA Institute website, along with an historical overview of how these accounting maneuvers survived after the financial crisis in 2008. Peters writes:

“What that means is that the financial statement carrying value of those financial instruments held-to-maturity is reflected at amortized cost, or what management paid for the asset sometime in the past plus amortization of the discount or premium from the face value. The fair value is only disclosed on the face of the financial statement and in the footnotes. Any unrealized loss is ‘hidden in plain sight.’

“But management intent and business model do not change the value of financial instruments. The HTM classification only makes it harder for investors and depositors to see.”

Peters then explains how this played out at the now collapsed Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), which went into receivership at the FDIC on March 10, creating billions of dollars in losses for the FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund and a contagion effect of other banks’ share prices collapsing:

“This is what SVB did. At 12/31/2022, SVB reflected $91.3 billion of HTM financial instruments, 43.1% of its balance sheet, at amortized cost. Their fair value was only $76.2 billion, or $15.1 billion less than their carrying value. With only $16.3 billion in book equity, this loss would have reduced equity, assuming the losses had no tax benefit, to $1.2 billion. Even with a tax benefit — if SVB could recoup all the tax benefit — this would amount to a $11.9 billion reduction in book equity…”

Peters calls this “Hide-‘til-Maturity” accounting. We agree.