By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: August 30, 2022 ~

According to YCharts (give the chart time to load) since January 1, 2017 through December 31, 2021 – a span of five years – JPMorgan Chase has spent a total of $84.312 billion buying back its own stock. In eight of those quarters, it spent more than $5 billion buying back its own shares.

In the three quarters when JPMorgan Chase was on a secret feeding tube from the Fed via the Fed’s emergency repo loans and other emergency programs, the bank bought back the most stock in its history according to YCharts: $6.949 billion for the quarter ending September 30, 2019; $6.751 billion for the quarter ending December 31, 2019; and $6.517 billion for the quarter ending March 31, 2020.

Now, the unthinkable has happened. The Fed has actually put JPMorgan Chase on a leash. As a result, the bank is currently unable to buy back its stock and, as a result, the bank’s shares are down 28 percent year-to-date.

JPMorgan Chase is the largest bank by assets in the United States with $3.48 trillion in assets as of March 31, 2022 according to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. Its peer banks are Bank of America with $2.5 trillion in assets as of the end of the first quarter; Wells Fargo with $1.76 trillion in assets on the same date; and Citigroup’s Citibank with $1.72 trillion in assets at the end of the first quarter.

As the chart below indicates, JPMorgan Chase is the worst performing stock among its peer banks as of the close of trading yesterday.

Why did the Fed put JPMorgan Chase on a leash regarding buybacks? According to the bank’s most recent quarterly report (10-Q) filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, the answer is as follows:

“As a result of the expected increase in the SCB [Stress Capital Buffer] in the fourth quarter of 2022 and GSIB [Global Systemically Important Bank] surcharge in the first quarter of 2023, the Firm has temporarily suspended share repurchases.”

There is also this nugget of information in the 10Q:

“As directed by the Federal Reserve, total net repurchases and common stock dividends in the first and second quarter of 2021 were restricted and could not exceed the average of the Firm’s net income for the four preceding calendar quarters.”

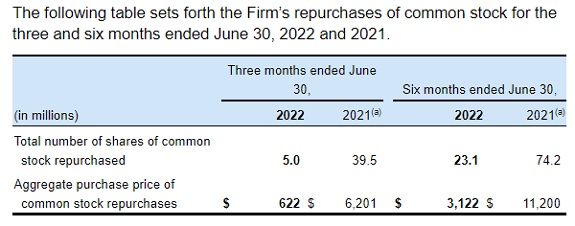

According to the table below that was inserted into JPMorgan Chase’s 10-Q for the quarter ending June 30, 2022, it spent $3.122 billion in the first six months of 2022 buying back its own stock versus $11.2 billion for the same period in 2021 – a shrinkage of 72 percent.

In July of 2017, Thomas Hoenig, then Vice Chair of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), sent a letter to the U.S. Senate Banking Committee. He made these points in his letter regarding banks using their capital to buy back their own stock and paying generous dividends to shareholders:

“[If] the 10 largest U.S. Bank Holding Companies [BHCs] were to retain a greater share of their earnings earmarked for dividends and share buybacks in 2017 they would be able to increase loans by more than $1 trillion, which is greater than 5 percent of annual U.S. GDP.

“Four of the 10 BHCs will distribute more than 100 percent of their current year’s earnings, which alone could support approximately $537 billion in new loans to Main Street.

“If share buybacks of $83 billion, representing 72 percent of total payouts for these 10 BHCs in 2017, were instead retained, they could, under current capital rules, increase small business loans by three quarters of a trillion dollars or mortgage loans by almost one and a half trillion dollars.”

What exactly do share buybacks do for the corporation? According to an analysis by Lenore Palladino for the Roosevelt Institute, buybacks work like this:

“Open-market share repurchases, often known informally as ‘stock buybacks,’ occur when companies purchase back their own stock from shareholders on the open market. When a share of stock is bought back, the company reabsorbs that portion of its ownership that was previously distributed among other investors. This reduces the amount of outstanding shares in the market, resulting in an increase in the price per share. The logic is that of supply and demand: when there are fewer supplies available to purchase, then an upward demand will increase share prices. In essence, then, stock buybacks raise share prices artificially. The value of the stock goes up as a result of a stock buyback, but without making the kinds of changes that would improve the actual value of the company—through more efficient production, new products, or better customer experience…”

Artificial inflation of JPMorgan Chase’s share price through buybacks might explain why the stock market has shrugged off five felony counts brought by the Justice Department against the bank since 2014 as its Board kept the same Chairman and CEO, Jamie Dimon, in place throughout the crime spree.

The Roosevelt Institute’s Palladino has some additional thoughts on exactly who is benefiting from this market manipulation of share prices. She writes:

“One of the major problems with stock buybacks is that corporate executives often hold large amounts of stock themselves, and their compensation is often tied to an increase in the company’s earnings per share (EPS) metric. That gives executives a personal incentive to time buybacks so that they can profit off of a rising share price. Usually a majority of corporate executives’ pay is from ‘performance-based pay,’ which is either directly paid in stock or compensation based on rising EPS metrics (Larckar and Tayan). That means that the decision of whether and when to execute a stock buyback can affect his or her compensation by tens of millions of dollars. Despite these facts—that stocks constitute a substantial proportion of executives’ pay, and that stock buybacks provide a way for executives to raise their pay by millions of dollars—the rules that govern how the company authorizes stock buyback programs fail to account for this significant conflict of interest. The decision to authorize a new stock buyback program is made by the board of directors, including interested directors (those who hold significant shares of stock). The actual execution of buybacks is left to the executives and financial professionals inside the companies, with no board oversight as to the timing or amount of such buybacks, as long as the buybacks stay within the limit previously authorized. As long as directors are using their best ‘business judgment’ to authorize programs, there is no recourse to hold directors accountable for extremely high repurchase programs….”

Last Monday we reported on a $1.8 billion loan in which JPMorgan Chase was involved to finance the largest ski resort deal in history. The family business of an 18-year member of JPMorgan Chase’s Board of Directors, James Crown, was a key participant in the deal. But the loan details were never disclosed in the bank’s public filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

JPMorgan Chase refers to James Crown as an “independent” Director. The bank writes in its proxy filing with the SEC that all of its non-management Board members had only “immaterial relationships with JPMorgan Chase,” thus they can be called independent. But $1.8 billion does not sound “immaterial” to us.

Equally of note, James Crown has directly benefited from the bank’s stock buyback binge. According to JPMorgan’s proxy filing this year, Crown is the beneficial owner of 12,282,729 shares of JPMorgan Chase stock. As of yesterday’s close, those shares had a market value of $1.4 billion. Dimon has the second largest holding of shares among Board Members, with a beneficial ownership of 8,487,173 shares, valued at $970.8 million as of yesterday’s close.

The $84 billion that the bank spent buying back its own stock from 2017 to 2021 directly benefited these two Board members (as well as other Board members with sizeable holdings of the stock).

Despite the clearcut evidence that stock buybacks by the largest depository banks in the U.S. enrich the 1 percent while depriving the U.S. economy of necessary capital, Congress has failed to outlaw the practice. Instead, Congress included a wimpy 1 percent excise tax on share buybacks when it recently passed the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. The bill was signed into law on August 16, 2022 by President Biden.