By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: October 11, 2021 ~

Regulation U is a 1936 Federal Reserve rule, that is still in force today, that allows federally-insured, taxpayer backstopped commercial banks to make margin loans for speculating in stocks. Unlike 1936, however, Wall Street trading houses are today allowed to own their own federally-insured, taxpayer backstopped commercial banks. That has allowed a lot of mischief to occur in the making of margin loans for speculating in the stock market. We’ll get to the details of all that in a few moments, but first some necessary background.

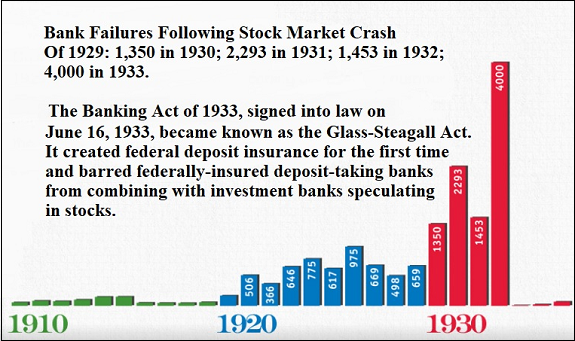

Following the 1929 stock market crash, 9,096 banks that were holding deposits for average Americans failed as a result of insolvency between 1930 and 1933. (See chart above.)

The 1930s banking crisis came to a head on March 6, 1933, just one day after President Franklin D. Roosevelt was inaugurated. Following a month-long run on the banks, Roosevelt declared a nationwide banking holiday that closed all banks in the United States. On March 9, 1933, Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act which allowed regulators to evaluate each bank before it was permitted to reopen. Thousands of banks were deemed insolvent and permanently closed.

There was no federal deposit insurance on bank deposits at that time, meaning that depositors lost all of their money in many cases or were paid just pennies on the dollar.

To restore the public’s confidence in the U.S. banking system, President Roosevelt signed into law the Banking Act of 1933, more popularly known as the Glass-Steagall Act after its authors Senator Carter Glass, a Democrat from Virginia, and House Rep Henry Steagall, a Democrat from Alabama. The legislation created federal deposit insurance for bank accounts for the first time in the U.S. while also banning these federally-insured banks from speculating in, or underwriting, stocks.

This separation of insured banking from the casino culture of Wall Street was not controversial at the time. Years of Senate Banking hearings following the ’29 crash had informed the Congress of that era, as well as the public through bold newspaper headlines, that it was Wall Street speculators gambling with depositors’ money that had caused the stock market crash and insolvency of the banks.

The Glass-Steagall Act protected the U.S. banking system for 66 years until its repeal during the Wall Street-friendly Bill Clinton administration in 1999. The momentum for its repeal came from the announcement in 1998 that Sandy Weill wanted to merge his trading firms, Salomon Brothers and Smith Barney (under the Travelers Group umbrella), with Citicorp, parent of the federally-insured Citibank commercial bank.

Weill had a self-confessed personal motive for this merger, which created the so-called “universal bank,” Citigroup. Weill told his merger partner, John Reed of Citibank, that his motivation for the deal was: “We could be so rich,” according to Reed in an interview with Bill Moyers.

The New York Times Editorial Board, shamelessly, became a sycophant for Wall Street in the push to repeal Glass-Steagall. On March 12, 1988, the New York Times published an editorial titled: “Dispel This Banking Myth.” It regurgitated false propaganda straight from Wall Street lobbyists. One paragraph read:

“The Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 was intended to prevent another market crash by prohibiting banks from selling and underwriting securities. But in practice it merely built a wall around banking, a barrier that reduced competition and raised fees in the closely related securities industry without adding to financial stability.”

In another editorial on September 22, 1990, the New York Times lauded “The Fed’s Sensible Bank Experiment.” It wrote:

“The Glass-Steagall Act was passed in part to settle a turf war between competing interests in U.S. financial markets. But it also reflected a belief, fueled by the 1929 crash on Wall Street and the subsequent cascade of bank failures, that banks and stocks were a dangerous mixture.

“Whether that belief made sense 50 years ago is a matter of dispute among economists. But it makes little sense now. In a recent study of Glass-Steagall, George Benston, a professor of finance at Emory University, provides compelling evidence that cutting off banks from stocks and bonds makes them more risky: a bank reduces risk by diversifying its investments.”

On April 8, 1998, the Times editorial writers effectively saluted John Reed and Sandy Weill for putting together a mega bank merger that was illegal at the time. They wrote:

“Congress dithers, so John Reed of Citicorp and Sanford Weill of Travelers Group grandly propose to modernize financial markets on their own. They have announced a $70 billion merger — the biggest in history — that would create the largest financial services company in the world, worth more than $140 billion… In one stroke, Mr. Reed and Mr. Weill will have temporarily demolished the increasingly unnecessary walls built during the Depression to separate commercial banks from investment banks and insurance companies.”

With the New York Times acting as a publicist for the repeal, President Bill Clinton signed into law the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act on November 12, 1999, which repealed the Glass-Steagall Act and its critical provisions for the separation of federally-insured banks from the Wall Street casino.

Just nine years later, Citigroup collapsed and was propped up with the largest taxpayer and Federal Reserve bailout in history. By March 2009, Citigroup was a 99-cent stock.

The immediate effect of the repeal of Glass-Steagall was that trading houses across Wall Street could now own federally-insured commercial banks and use the banks’ hundreds of billions of dollars in insured deposits to speculate in stocks and derivatives. Every major Wall Street trading house either bought a federally-insured bank or created one.

What Weill meant by “We could be so rich” was this: If the trading bets won big, the bank CEOs became obscenely rich on stock-option-based performance pay. When the bets lost big, the government and the Federal Reserve would be forced to do a bailout rather than allow a giant, interconnected, federally-insured bank to fail.

In 2008, just nine years after the repeal of Glass-Steagall, century-old, iconic Wall Street banks blew themselves up in a replay of 1929. In addition to the widely publicized government bailout known as TARP, the Federal Reserve, which was supposed to be the supervisor of these mega bank holding companies and prevent this kind of a banking crisis, went into stealth mode and began funneling astronomical sums to prop up the banks and its own reputation. Without one vote in Congress, the Fed secretly funneled $29 trillion in cumulative loans to bail out the Wall Street banks, their trading operations in London, their foreign bank derivative counterparties, and foreign central banks through dollar swap lines. The media had to engage in a multi-year court battle to finally obtain the hideous details of the Fed’s loans.

The Fed correctly knew that once the size of the loans was revealed, its abject failure as a supervisor of the mega banks would also be revealed. Despite this, however, Congress gave the Fed enhanced powers to supervise the same mega banks under the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010 – which has left the United States with a perilous banking system today.

Both Weill and Reed did, indeed, become obscenely rich (see here and here) while millions of Americans lost their jobs and their homes to foreclosure during the Great Recession that followed the 2008 crash.

One of the key culprits to the 1929 crash and the market devastation that followed over the next four years (the stock market lost 89 percent of its value from 1929 to 1933) was the lack of controls and oversight of margin loans for stock speculation.

On June 6, 1934, the Senate Banking Committee released a detailed report summarizing its findings on the causes of the crash from its years of hearings, which were known variously as the Pecora Hearings or the “Stock Exchange Practices” hearings.

The Senate Banking report noted that because the Wall Street trading houses were “Excited by the vision of quick profits, they assumed margin positions which they had no adequate resources to protect, and when the storm broke they stood helplessly by while securities and savings were washed away in a flood of liquidation.”

The report more specifically outlined the dangerous impact of margin loans as follows:

“Brokers obtain funds to finance their own and their customers’ margin transactions chiefly by borrowing from banking institutions. Banks, in turn, make these loans on their own behalf or act as agents in lending the funds of nonbanking corporations, individuals, and investment trusts, commonly designated as ‘others.’ Brokers also borrow in large volume from nonbanking corporations having available cash, without the intervention of banks.

“When the volume of brokers’ loans piles up to the heights reached in recent years, the situation is fraught with peril. In the event of unfavorable developments in the financial world, such loans are promptly called, the borrowers are forced to sell securities on a vast scale, and a decline in security values is precipitated. With the drop in market prices, margin accounts become under-margined, resulting in further involuntary liquidation, which accelerates the decline. The shrinkage in security prices not only demoralizes the margin trader, but impairs the security of collateral loans made by the banks and the value of securities held in their own portfolios. Thus, the lending institutions suffer loss because of the decline in security values occasioned by swift contraction of the volume of brokers’ loans.”

If you are an American citizen, endowed with a sound mind and intellect, you are likely thinking that there is no way that the Congress of the United States would have created federal-deposit insurance in 1933, backstopped by the U.S. taxpayer, while continuing to allow these federally-insured banks to provide margin loans to the Wall Street casino.

Actually, Congress did worse than that in 1934. It passed the buck to the Federal Reserve to implement margin rules. The Senate Banking report explains it this way:

“The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 subjects all speculative credit to the central control of the Federal Reserve Board as the most experienced and best-equipped credit agency of the Government…These provisions are intended to protect the margin purchaser by making it impossible for him to buy securities on too thin a margin, and to vest the Government credit agency with power to reduce the aggregate amount of the Nation’s credit resources which can be directed by speculation into the stock market and away from commerce and industry.”

For why the Federal Reserve is a captured regulator that perpetually resorts to bailing out the banks instead of actually supervising them, see our report: These Are the Banks that Own the New York Fed and Its Money Button.

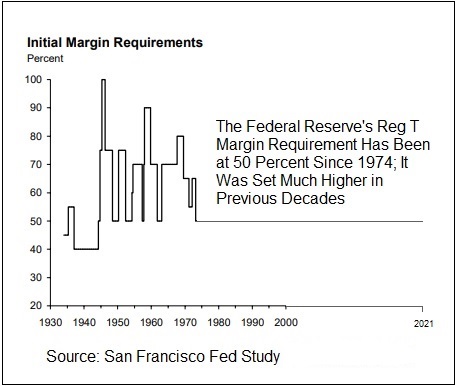

The Federal Reserve’s margin regulation for broker-dealers providing credit to customers on Wall Street is Regulation T. Prior to January 3, 1974, Reg T’s initial margin requirement went as high as 80, 90 and 100 percent. Since January 3, 1974, Reg T’s initial margin requirement has been set at 50 percent.

Which brings us back to Regulation U – the dangers of which the Senate Banking Committee has ignored for at least the last two decades. The Federal Reserve’s Regulation U covers extending credit secured with margined stock by federally-insured commercial banks, savings and loan associations, federal savings banks, credit unions, production credit associations, insurance companies, and companies that have employee stock option plans. Reg U currently carries the same 50 percent margin requirement as Reg T – but Reg U has a myriad of exceptions and exemptions that Wall Street can, and does, easily maneuver around.

The call reports that the federally-insured banks file with regulators are supposed to capture the size of their Reg U margin loans on Schedule RC-C, part I, item 9.b. We took a close look at those reports for the most recently filed quarter ending on June 30, 2021. The line item is titled: “Loans for purchasing or carrying securities (secured and unsecured).” Among the mega banks, Bank of America has the largest amount of loans extended, at $17.96 billion. JPMorgan Chase was next, at $12.8 billion. State Street Bank and Trust was third in line at $9.73 billion, followed by Bank of New York Mellon at $8.6 billion.

The trading powerhouse, Morgan Stanley, is allowed to own two federally-insured banking institutions as a result of the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act. The Morgan Stanley Private Bank National Association has extended $3.07 billion in margin loans while the Morgan Stanley National Association has extended $2.09 billion.

We did not have the time to go through the call reports for the approximate 5,000 federally-insured banks in the United States to see how much credit they have extended for stock speculation with margin loans, but we did stumble on one piece of unsettling data. The Northern Trust Company has only $53 billion in deposits, unlike a JPMorgan Chase or Bank of America which have over $2 trillion and $1.87 trillion, respectively, in deposits. And yet, the Northern Trust Company shows that it had made $4.03 billion in margin loans as of June 30. That suggests that 7.55 percent of its deposits are going to market speculation instead of for loans to help the real economy recover from the worst pandemic in a century.

But the dollar amount of margin loans appearing on Schedule RC-C, part I, item 9.b. is just the tiny tip of the iceberg in terms of explaining today’s unprecedented stock market bubble.

According to the bank instructions for preparing Schedule RC-C, “Loans to holding companies of depository institutions” go on a separate line, part I, item 9.a. Every major Wall Street bank is part of a bank holding company. The loans on line 9.a. are, in all cases, exponentially larger than line 9.b.

Another, as yet unexamined, threat to the U.S. banking system is the undefined dollar amount of margin loans that are masquerading as total return swaps – effectively loaning out the balance sheets of the federally-insured banks to hedge funds.

The public learned in March of this year that a family office hedge fund, Archegos Capital Management, was not anywhere on bank regulators’ radar screens when it blew up, causing total losses of more than $10 billion to a group of mega banks that included Credit Suisse, Morgan Stanley, UBS, Nomura and others. In some cases, only 15 percent margin was provided by Archegos with banks providing 85 percent credit. See our report Archegos: Wall Street Was Effectively Giving 85 Percent Margin Loans on Concentrated Stock Positions – Thwarting the Fed’s Reg T and Its Own Margin Rules.

There hasn’t been a peep provided to the American people by bank regulators since the Archegos blowup to indicate just how widespread this swap/margin loan deception is at the banks. Wall Street insiders say it is very widespread and has been going on for at least 15 years.

Just how much of the life savings of moms and pops across America, that were deposited into federally-insured banks for safety, not to finance hedge funds insatiable greed, have been diverted away from the real economy into some manner of margin loans? No bank regulator actually knows, or if they do, they’re not talking.

On September 23 the Federal Reserve released its Z.1 statistical release on the Financial Accounts of the United States. The section on “Corporate Equities” shows that at the end of 2019, the market value of all publicly-traded equities (stocks) in the U.S. stood at $38.47 trillion. By the end of the second quarter of 2021, in the midst of an ongoing National Emergency and the worst health crisis in more than a century, the market value of all publicly-traded equities had surged to $54.768 trillion, an increase of 42 percent in a year and a half. (See page 130, Line 29 at this link.)

The U.S. stock market, at $54.768 trillion, is larger than the combined GDP of the United States, China, Japan, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and the U.K. according to GDP data from the World Bank.

It’s long past the time for the Senate Banking Committee to hold hearings, take testimony under oath, subpoena documents and get to the bottom of this dangerous Wall Street/Banking/Federal Reserve explosive cocktail.