By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: June 26, 2020 ~

Yesterday the Federal Reserve released its highly awaited stress tests on the biggest and most dangerous banks in America. The stress test results fill an 83-page document with dozens of charts showing what would happen to the banks under a hypothetical “severely adverse scenario.”

This scenario, unfortunately, was previously prepared and pales in comparison to the actual economic damage rendered by the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the severely adverse scenario for this year’s stress tests imagined the U.S. unemployment rate climbing to a peak of 10 percent in the third quarter of 2021. The unemployment rate is currently 13.3 percent. But far more frightening, the Fed’s severely adverse scenario for GDP imagined a decline of “8½ percent from its pre-recession peak, reaching a trough in the third quarter of 2021.”

As of yesterday, June 25, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow estimate was for U.S. GDP to decline by a staggering 46.6 percent in the second quarter. In a feeble attempt to compensate for the fact that its “severely adverse scenario” now looks like a cake walk compared to the reality on the ground in the U.S., the Fed added what it calls a “sensitivity analysis.” That analysis assessed how the big banks would perform under three downside scenarios resulting from the coronavirus pandemic: a V-shaped recession; a slower, U-shaped recession; and a more severe W-shaped, double-dip recession.

The Fed summarized those three scenarios as follows: “Under the U- and W-shaped scenarios, most firms remain well capitalized but several would approach minimum capital levels.”

The Fed, however, did not provide individual bank results for those scenarios. It provided individual bank results only for its previously announced criteria for the “severely adverse scenario” that imagined unemployment at 10 percent and a GDP decline of 8.5 percent. Under that scenario, the Fed projected $552 billion in losses in the aggregate for the 33 banks it reviewed, over nine quarters.

We looked at where those projected losses were concentrated and, sure enough, they were concentrated at the biggest Wall Street banks. The breakdown was as follows: JPMorgan Chase, hypothetical losses of $64.4 billion; Citigroup, $47.7 billion; Wells Fargo, $47.4 billion; and Bank of America, $47.2 billion. In other words, the tally for just those four banks comes to $206.7 billion or 37 percent of the losses for all 33 banks.

The Fed really lost credibility, however, with these loss estimates for Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, showing hypothetical losses of $9.8 billion and $5.3 billion, respectively, in the hypothetical “severely adverse scenario.” During the last financial crisis, one trader alone at Morgan Stanley, Howie Hubler, racked up $9 billion in losses.

The Fed’s Vice Chair for Supervision, Randal Quarles, released this statement along with the stress test results:

“The banking system has been a source of strength during this crisis and the results of our sensitivity analyses show that our banks can remain strong in the face of even the harshest shocks.”

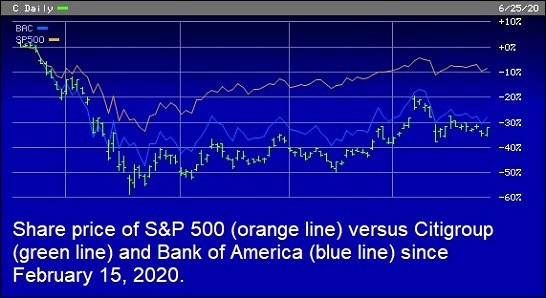

But the trading patterns of these bank stocks tell a very different story. The chart above shows how two of the biggest bank stocks, Citigroup and Bank of America, have fared since February 15 versus the Standard and Poor’s 500 broader market average. The losses on the share prices of the bank stocks have dramatically outpaced the broader market.

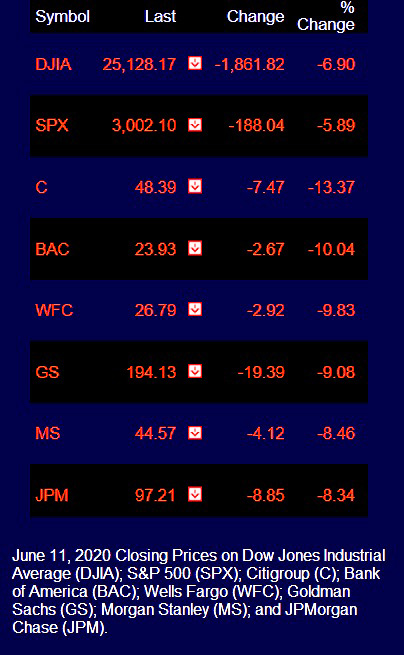

Then there is the fact that when the stock market experiences a sharp selloff, all of the biggest Wall Street bank stocks sell off far in excess of the broader market. That’s decidedly not how these bank stocks should be behaving if they are indeed a “source of strength.” Take June 11 of this year for example, as shown in the chart below. The S&P 500 experienced a decline of 5.89 percent while Citigroup lost 13.37 percent. Bank of America tanked by 10.04 percent while the largest bank in the country, JPMorgan Chase, which is under a criminal probe for allowing its precious metals desk to be reengineered into a racketeering enterprise, according to the U.S. Department of Justice, fell by 8.34 percent.

We are simply not persuaded that the biggest banks on Wall Street, which account for the bulk of the $202 trillion notional in derivatives, are going to provide the strength the U.S. needs to weather this unprecedented storm.

Another skeptic is Federal Reserve Board Governor Lael Brainard, who released her own dissenting opinion on the Fed allowing these banks to continue making dividend payouts. Brainard wrote the following in that regard:

“[The Fed] vote allows distributions to continue to be paid out, despite the material change in financial conditions. It implements a novel approach by authorizing third quarter dividends at a level equal to average net income over the prior four quarters—even though that past net income and more was already paid out in the prior quarters. The payouts will amount to a depletion of loss absorbing capital. This is inconsistent with the purpose of the stress tests, which is to be forward looking by preserving resilience, not backward looking by authorizing payouts based on net income from past quarters that had already been paid out.”