Deutsche Bank Trading Chart from February 14 through March 5 Versus AIG, Ameriprise Financial (AMP), Prudential Financial (PRU), Lincoln National (LNC), JPMorgan Chase (JPM), Bank of America (BAC), Morgan Stanley (MS), Goldman Sachs (GS) and Citigroup (C).

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: March 6, 2020 ~

Yesterday, the Dow Jones Industrial Average of 30 large cap companies closed with a loss of 969.5 points or 3.58 percent. That was bad enough but the losses among the biggest Wall Street banks outpaced the Dow losses by a significant margin. Typically, JPMorgan Chase is one of the better performers among the Wall Street banks in the midst of a big selloff. But not yesterday. It closed with a loss of 4.91 percent – a loss larger than Goldman Sachs (- 4.77 percent), which has a large criminal fine hanging over its head. The news that Jamie Dimon, Chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase, had heart surgery on Thursday was not reported until after the stock market had closed.

The losses among the other mega banks on Wall Street yesterday were equally unsettling. Morgan Stanley lost 5.86 percent; Citigroup closed down 5.79 percent, while Bank of America shed 5.07 percent.

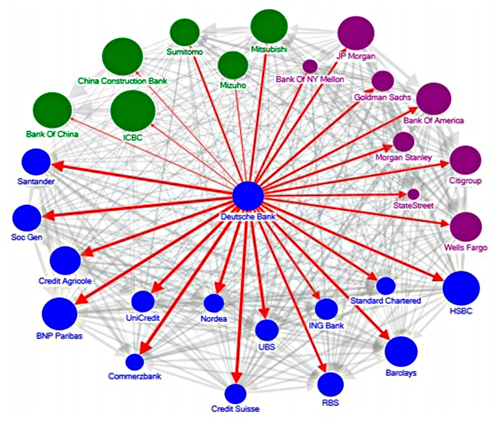

All of these banks have one thing in common: they each are exposed to tens of trillions of dollars in derivatives. And according to a 2016 report from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the German mega bank, Deutsche Bank, is heavily interconnected via derivatives to each of these Wall Street banks. (See chart below.) Deutsche Bank’s stock lost 5.49 percent yesterday, bringing its losses to 30 percent in just the past 15 trading sessions. That’s common equity capital that Deutsche Bank can’t afford to lose: its shares have lost 75 percent of their common equity value in the past five years. The IMF concluded that Deutsche Bank posed a greater threat to global financial stability than any other bank as a result of these interconnections – and that was when its market capitalization was tens of billions of dollars larger than it is today.

On July 21, 2011, when the Government Accountability Office (GAO) released its audit of the Federal Reserve’s secret $16.1 trillion in bank bailout loans during the financial crisis, the bank that ranked number 9 on the list for the largest amount of loans wasn’t even a U.S. bank – it was Deutsche Bank. The Fed had funneled a cumulative $354 billion in revolving loans to Deutsche Bank. Two other foreign banks had received even more in Fed loans than Deutsche Bank: the U.K. bank, Barclays, had received $868 billion while the Royal Bank of Scotland Group PLC, also of the U.K., had received $541 billion from the Fed.

This inexplicable largesse from the Fed to foreign banks (while millions of American homeowners did not get a bailout and lost their homes to foreclosure) came into sharper perspective when the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission released this chart. The chart shows Goldman Sachs’ derivative counterparties as of June 2008 and the dollar amount of that exposure. Between Deutsche Bank, Barclays, and the Royal Bank of Scotland, Goldman had a cumulative derivatives’ exposure to just those three foreign banks of $7.2 trillion notional (face amount).

Factor in the derivatives exposure at that time to these foreign banks by Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch and one can begin to understand why the Federal Reserve wanted to keep its $16.1 trillion in revolving loans to both domestic and foreign banks a big secret from the American people. (The GAO audit of the Fed only came about as a result of Senator Bernie Sanders attaching an amendment to the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation in 2010.)

To help convince the public that the Wall Street banks were safe and sound again after the financial crisis of 2008 (despite the fact that they continued to have these astronomical sums of derivative exposure), the Fed began to make a big show out of its annual stress tests of the mega banks. But in 2016, when researchers at the Office of Financial Research looked at how the Fed was conducting these stress tests, they concluded that the Fed was not drilling down to the critically important data.

The OFR researchers who conducted the study, Jill Cetina, Mark Paddrik, and Sriram Rajan, concluded that the Fed’s stress tests are measuring counterparty risk for the trillions of dollars in derivatives held by the largest banks on a bank by bank basis. The real issue, wrote the researchers, is the contagion that could spread rapidly if one big bank’s counterparty was also a key counterparty to other systemically important Wall Street banks. The researchers wrote:

“A BHC [bank holding company] may be able to manage the failure of its largest counterparty when other BHCs do not concurrently realize losses from the same counterparty’s failure. However, when a shared counterparty fails, banks may experience additional stress. The financial system is much more concentrated to (and firms’ risk management is less prepared for) the failure of the system’s largest counterparty. Thus, the impact of a material counterparty’s failure could affect the core banking system in a manner that CCAR [one of the Fed’s stress tests] may not fully capture.”

The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, the official government body that examined the underpinnings of the 2008 implosion on Wall Street, said this about the role of derivatives in the crisis: “the existence of millions of derivatives contracts of all types between systemically important financial institutions—unseen and unknown in this unregulated market—added to uncertainty and escalated panic, helping to precipitate government assistance to those institutions.”

But foreign banks are not the only counterparties to Wall Street mega banks’ derivatives. As we reported on February 25, U.S. insurers are also significant counterparties to Wall Street’s derivatives. As the chart above indicates, the insurer, Lincoln National, which has derivative ties to Wall Street banks, has been trading in a notably close correlation to Deutsche Bank, losing 33 percent in the past 15 trading sessions. Other insurers with derivative counterparty exposure to Wall Street, such as AIG, Ameriprise Financial, and Prudential Financial have also experienced losses that outpace the broader averages.

Systemic Risk Among Deutsche Bank and Global Systemically Important Banks (Source: IMF — “The blue, purple and green nodes denote European, US and Asian banks, respectively. The thickness of the arrows capture total linkages (both inward and outward), and the arrow captures the direction of net spillover. The size of the nodes reflects asset size.”)