By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: October 29, 2019 ~

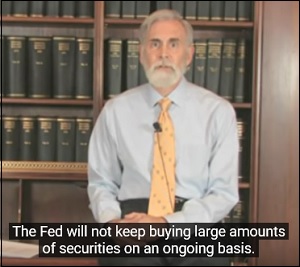

On January 19, 2011, the Federal Reserve released a video on YouTube to quell the public uproar over its unaccountable money creation operations. The spokesman for the Fed in the video was their Senior Adviser at the time, Steve Meyer, now an Adjunct Professor of Finance at The Wharton School. The Fed was in the middle of its second round of quantitative easing (QE2) and Meyer states this: “The Fed will not keep buying large amounts of securities on an ongoing basis.” The Fed was so intent on conveying the “temporary” nature of its unprecedented actions that it put that statement by Meyer on the screen. (See screen shot above.) Meyer then immediately adds this about the Fed: “Its purchases are a temporary measure to help the economy recover.”

But the Fed’s purchases were not temporary. On September 13, 2012 the Fed announced QE3, indicating it would be “purchasing additional agency mortgage-backed securities at a pace of $40 billion per month.” And on December 12, 2012 the Fed expanded QE3 with the announcement that it would “continue purchasing additional agency mortgage-backed securities at a pace of $40 billion per month” and would also “purchase longer-term Treasury securities…initially at a pace of $45 billion per month.”

By 2015, the Fed had increased its balance sheet to $4.5 trillion from the $800 billion it had been prior to the financial crisis. Despite all of the Fed’s promises to “normalize” its balance sheet, today its balance sheet stands at $4 trillion and on September 17 of this year it launched a new, massive money pumping operation on Wall Street’s behalf.

Today, the U.S. is supposedly still in an economic expansion with an unemployment rate of 3.5 percent, one of the lowest rates in the past half-century, and yet the Fed has reinstituted a massive money pumping operation to Wall Street. (See Fed Ups Its Wall Street Bailout to $690 Billion a Week as Media Snoozes.)

The Fed’s crisis-era quantitative easing programs had something in common with the Congressionally-approved Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). Both were shiny objects to distract the public from the obscenely giant money funnel that the Fed was secretly providing to Wall Street through a mish-mash of acronyms too numerous for anyone to keep track of. When the Levy Economics Institute tallied it all up, the tab came to $29 trillion in cumulative loans and other forms of relief to bail out Wall Street. See Table 16 at this link. (The $29 trillion includes $1.85 trillion in purchases of agency mortgage-backed securities that overlap with part of the Fed’s quantitative easing operations.)

In the Fed video, Steve Meyer also confronts the elephant in the room: where is the Fed getting all of this money to bail out Wall Street for its greedy excesses that led to it blowing itself up.

Meyer says this at 3:42 minutes on the video:

“You may wonder how the Fed pays for the bonds and other securities it buys. The Fed does not pay with paper money. Instead, the Fed pays the sellers’ bank using newly created electronic funds, and the bank adds those funds to the sellers’ account. The seller can spend the funds or can simply leave them in the bank. If the funds stay in the bank, then the bank can increase its lending, purchase more assets, or build up the reserves it holds on deposit at the Fed. More broadly, the Fed’s securities purchases increase the total amount of reserves that the banking system keeps at the Fed.

“Whether the Fed’s purchases lead to an increase in the amount of money circulating in the economy depends on what banks do with the new reserves and on what sellers do with the funds they receive.”

The big problem with this statement is the use of the word “bank.” Prior to 1999, banks were traditional depository institutions that took in federally-insured deposits from moms and pops and loaned that money out to credit-worthy businesses and consumers in order to grow the U.S. economy and keep the U.S. competitive on the world stage. But in 1999, after the Clinton administration repealed the Glass-Steagall Act, which had kept the U.S. financial system safe for 66 years by barring the combination of federally-insured deposit-taking banks with the high-risk investment casino banks on Wall Street, the word “bank” had lost its traditional meaning when it came to the new conglomerates on Wall Street.

The most striking example of what these mega “banks” had become was revealed in 2012 when JPMorgan Chase, the largest “bank” in the country, was exposed for having used hundreds of billions of dollars from its federally-insured “bank” to gamble in exotic derivatives in London, eventually losing at least $6.2 billion of its depositors’ money.

What this new banking model has also done is to allow these mega “banks” on Wall Street to create the greatest income and wealth inequality in the U.S. since the late 1920s (before the passage of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933) by using the super cheap money from the Fed to buy back their own stock, pump up their share prices, and then reward their top executives with millions of shares of inflated stock.

To make this situation even more of a Keystone Cops farce, Congress has yet to hold a hearing on the Fed’s latest interventions to bail out Wall Street. This follows Congress deciding in the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010, which was supposed to address the worst financial collapse since the Great Depression because of greed and corruption on Wall Street, to give the crony Fed the primary job of overseeing the biggest bank holding companies on Wall Street. That work is now supervised by the New York Fed, the same regional Fed bank that funneled the bulk of that $29 trillion to Wall Street during the financial crisis and the same Fed bank running today’s money spigot. (See Is the New York Fed Too Deeply Conflicted to Regulate Wall Street?)