The New York Times Fawns Over Charles E. Mitchell, Head of National City Bank, for His Gobbling Up of Other Banks (September 29, 1929)

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: September 13, 2018 ~

For more than a century, the New York Times has championed some of the most despised men on Wall Street in their power grabs of other banks. The resulting mega bank concentration has crippled competition, crippled democracy in the U.S. and led to unprecedented wealth and income inequality in our nation. And yet, to many Americans, the New York Times is considered a progressive newspaper.

It is notable that the New York Times was founded with big bank money. Adolph S. Ochs purchased the New York Times in 1896 for $75,000. John Pierpont Morgan Sr. of the powerful Wall Street bank, JPMorgan, provided $25,000 of that money. When the Times celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1996, it noted that the Pierpont Morgan Library was exhibiting “the original letter Ochs wrote to his wife, Effie, describing a meeting he had with J. Pierpont Morgan asking for help in financing the purchase of the paper.” In the letter Ochs said: “It took me just 15 minutes to secure Mr. Morgan’s signature for $25,000, and I walked out on air with his signature in my inside pocket.”

That friendship worked out well for John Pierpont Morgan Sr. During and after the Wall Street panic of 1907, the New York Times lionized Morgan as the man who saved the day. Morgan was also defended by the Times in 1912 during the Pujo Congressional hearings into the money trusts that ruled Wall Street and the nation’s finances.

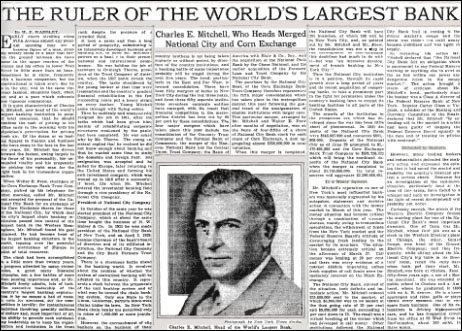

Another despised character, Charles E. Mitchell, who headed National City Bank (the precursor to today’s Citigroup) in the leadup to the 1929 Wall Street crash also found great affection at the New York Times for his gobbling up of competitors. In a nauseatingly adoring “news article” that ran on Sunday, September 29, 1929 under the headline “The Ruler of the World’s Largest Bank,” the Times portrayed Mitchell as something akin to a super action hero:

“Of the dozen or so leading figures in finance and business who have come to the fore in the last few years, Mr. Mitchell has driven forward the fastest, owing largely to the force of his personality, his unbounded vitality and his propensity for picking the right man for the right task in his tremendous organization.” The Times also felt it was important to share this with its readers: “He is a keen sportsman and rides, golfs or plays tennis every moment that he can spare from business. One of his relaxations is driving high-powered cars…”

The article was celebrating another takeover by National City, writing as follows:

“Thus the National City institution is in a position, through its rapid growth over a long period of years and its recent acquisition of competing banks, to take a prominent part in the fight for permission under the country’s banking laws to extend its banking facilities to all parts of the United States.”

The article bragged further that National City’s deposit base had expanded from $649 million in 1921 to $1.47 billion as of June 1929.

With no commentary at all on the crippling of competition these buyouts were causing, the Times article simply noted in passing that “There have been fifty merger of banks in New York City during the last three years, and from these fifty separate institutions, seventeen corporate entities have emerged, with the result that financial competition in the metropolitan district has been cut by 65 per cent by these consolidations.”

Exactly one month after this article appeared in the Times, the stock market began the worst crash in history, losing 90 percent of its value over the next three years. It would not regain the level it had set in 1929 until 25 years later. The Pecora Senate hearings on the crash pegged Mitchell as one of the most vile actors in the leadup to the crash, speculating in his own bank securities, making illegal trades and engaging in income tax evasion. One of the key Senators involved in the investigation, Senator Carter Glass, said of him: “Mitchell more than any 50 men is responsible for this stock crash.”

The Senate investigation proved that greedy Wall Street men could not be trusted with savings deposits. In 1933 Congress enacted the Glass-Steagall Act which permanently barred Wall Street firms underwriting securities from merging with banks holding deposits. Those deposits also became Federally insured under the Glass-Steagall Act. That legislation kept the U.S. financial system safe for the next 66 years until its repeal, aided by the New York Times, in 1999.

The Times began to overtly cheerlead for the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1988, writing:

“Few economic historians now find the logic behind Glass-Steagall persuasive. Banks did lose some money in the crash, but largely through defaults of loans secured by stock. Restrictions on investors’ ability to buy stock on credit would have helped to protect the banks, but not the Glass-Steagall prohibitions on selling or underwriting securities.”

That statement stands as a complete contradiction of the findings of the 3-year Senate investigation into the causes of the 1929-1932 crash. Investigators found that the Wall Street banks that were underwriting securities were also creating “pool operations” where they coordinated pumping up share prices until they could sell at a big profit. This created an artificially inflated market and undermined the safety and soundness of their banks, which also held savings deposits.

In 1990 the Times again attacked the Glass-Steagall Act, writing:

“The Glass-Steagall Act was passed in part to settle a turf war between competing interests in U.S. financial markets. But it also reflected a belief, fueled by the 1929 crash on Wall Street and the subsequent cascade of bank failures, that banks and stocks were a dangerous mixture.

“Whether that belief made sense 50 years ago is a matter of dispute among economists. But it makes little sense now…”

Smelling victory in the push to repeal Glass-Steagall, on April 8, 1998 the New York Times said this on its editorial page:

“Congress dithers, so John Reed of Citicorp and Sanford Weill of Travelers Group grandly propose to modernize financial markets on their own. They have announced a $70 billion merger — the biggest in history — that would create the largest financial services company in the world, worth more than $140 billion… In one stroke, Mr. Reed and Mr. Weill will have temporarily demolished the increasingly unnecessary walls built during the Depression to separate commercial banks from investment banks and insurance companies.”

The merger went through and one year later, in 1999, the Bill Clinton administration repealed the Glass-Steagall Act. Just nine years later, Wall Street collapsed in the same epic fashion as 1929, leaving the U.S. economy in shambles.

Citigroup, the successor to Charles E. Mitchell’s National City Bank, became a penny stock, trading at 99 cents during the crash. Its shareholders lost 90 percent of their money. Citigroup also received the largest taxpayer bailout in U.S. history. Mitchell’s modern-day successor at the bank, Sanford (Sandy) Weill, walked away a billionaire from his obscene stock awards while the bank was flying high.