By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: June 21, 2016

At 10 a.m. this morning, Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen will take her seat before the U.S. Senate Banking Committee to deliver her semi-annual testimony on monetary policy. She’ll perform the same task tomorrow before what is likely to be a far more hostile House Financial Services Committee, based on the fireworks that were flying in her last testimony there in February.

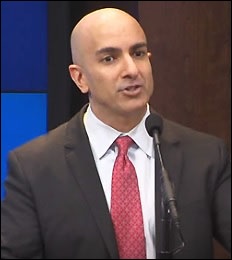

There will be a shadow wafting over Yellen at both hearings. The shadow is being cast by Neel Kashkari, who took the reins as President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis this past January and has effectively transferred the debate on too-big-to-fail banks from the hands of Yellen to his own regional institution. Kashkari has been conducting symposiums and delivering speeches on the issue and has promised a formalized plan to deal with the problem by the end of this year.

Just yesterday, Kashkari spoke at the Peterson Institute in Washington, D.C. and shot full of holes Yellen’s plan to shore up big bank capital with convertible debt (the so-called Total Loss-Absorbing Capacity or TLAC plan). Kashkari, who worked at the U.S. Treasury during the 2008 financial crisis and oversaw the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), offered this critique yesterday on why the convertible debt plan will not prevent more taxpayer bailouts of the mega banks:

“Do we really believe that in the middle of economic distress when the public is looking for safety that the government will start imposing losses on debt holders, potentially increasing fear and panic among investors? Policymakers didn’t do that in 2008. There is no evidence that their response in a future crisis will be any different….

“A policy analyst recently asked me if we really could resolve a large bank during a crisis. I responded by asking him if he thought we could dismantle an aircraft carrier in the middle of a hurricane. It’s not a perfect analogy, but he got my point…

“I object to this approach for two reasons. First, it immediately reinforces my concern about complexity. Second, this approach assumes that all-knowing, well-intentioned regulators, seizing a bank earlier, will somehow reduce the total losses the bank ultimately faces. I vividly remember the collapse of Bear Stearns in March 2008. In a couple of weeks, Bear Stearns went from normal operations to insolvency.”

The only quibble we have with Kashkari on the above point is that he had a much more powerful bank meltdown to offer. Citigroup, a banking monster compared to the diminutive Bear Stearns, melted away in one week, not a couple of weeks. Here’s how we reported the vaporization of Citigroup in the midst of the 2008 financial crash:

“Citigroup’s five-day death spiral last week was surreal. I know 20-something newlyweds who have better financial backup plans than this global banking giant. On Monday came the Town Hall meeting with employees to announce the sacking of 52,000 workers. (Aren’t Town Hall meetings supposed to instill confidence?) On Tuesday came the announcement of Citigroup losing 53 percent of an internal hedge fund’s money in a month and bringing $17 billion of assets that had been hiding out in the Cayman Islands back onto its balance sheet. Wednesday brought the cheery news that a law firm was alleging that Citigroup peddled something called the MAT Five Fund as ‘safe’ and ‘secure’ only to watch it lose 80 percent of its value. On Thursday, Saudi Prince Walid bin Talal, from that visionary country that won’t let women drive cars [Saudi Arabia], stepped forward to reassure us that Citigroup is ‘undervalued’ and he was buying more shares. Not having any Princes of our own, we tend to associate them with fairytales. The next day the stock dropped another 20 percent with 1.02 billion shares changing hands. It closed at $3.77.

“Altogether, the stock lost 60 per cent last week and 87 percent this year. The company’s market value has now fallen from more than $250 billion in 2006 to $20.5 billion on Friday, November 21, 2008. That’s $4.5 billion less than Citigroup owes taxpayers from the U.S. Treasury’s bailout program.”

Here’s what it took eventually from taxpayer to shore up this serially mismanaged mega bank: $45 billion in equity infusions, over $300 billion in asset guarantees, and more than $2 trillion in secret, cumulative revolving loans from the Federal Reserve at below market interest rates.

By one Reuters analysis, Citigroup had an astronomical 280x leverage ratio at the peak of the crisis in 2008, $2 trillion in assets on its books, and $1.2 trillion off its books, despite the fact that it was overseen by five Federal regulators at the time.

Kashkari’s rolling symposiums and refrain that Dodd-Frank did not end too-big-to-fail are getting a lot of angry pushback from the big Wall Street banks. Kashkari stated in his speech yesterday that “not surprisingly, we have received significant criticism from big banks and their lobbyists who would like to discredit this important initiative.”

The one concern about Kashkari is that in an earlier incarnation he worked at Goldman Sachs, which transformed itself into a bank holding company during the 2008 crash in order to get its share of taxpayer bailouts and cheap loans from the Fed. Goldman Sachs is predominantly an investment bank and has only a small presence in commercial banking. Kashkari has also floated the idea of capping a bank’s asset size. That would tend to help Goldman Sachs compete better against the much larger Wall Street banks that own massive commercial banks as well as investment banks and retail brokerage firms.

What Kashkari isn’t pounding the table for is the restoration of the Glass-Steagall Act which would entirely separate the commercial banks holding taxpayer-backstopped insured deposits from the high-risk-taking investment banks and brokerage firms. Until Kashkari opens that debate for a full airing, it would be wise to remain skeptical about his agenda.