By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: May 16, 2016

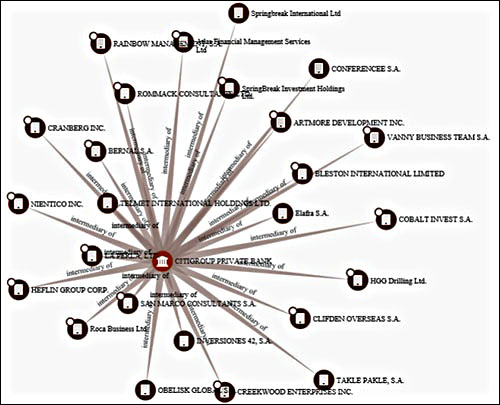

The Citigroup Private Bank at 201 South Biscayne Blvd. in Miami is located in a 34-story building in downtown Miami with breathtaking views of Biscayne Bay. It’s also the address for dozens of offshore companies whose agent is Mossack Fonseca, the law firm at the center of the Panama Papers scandal. The graph below shows just some of those companies, a number of which were incorporated as recently as 2013 through 2015. (Some companies indicate they are no longer active.) This new information comes from a search of the public database made available by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), which received more than 11.5 million leaked files from the Panama-based law firm, Mossack Fonseca, which ICIJ calls “one of the world’s top creators of hard-to-trace companies, trusts and foundations.” The full cache of records has yet to be made public and is being investigated by journalists around the world.

To fully appreciate Citigroup’s links to the Panama Papers scandal, a bit of history is in order. Citigroup was publicly thrashed by Senators Susan Collins and Carl Levin, Chair and Ranking Member, respectively, of the Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations following an in-depth investigation in 1999 of its facilitation of moving hundreds of millions of dollars of looted wealth by heads of state or their relatives from struggling countries to secret accounts in offshore havens. Senator Levin explained how private banks work at the November 9, 1999 hearing:

“Once a person becomes a client of a private bank, the bank’s primary goal generally has been to service that client, and servicing a private bank client almost always means using services that are also the tools of money laundering: secret trusts, offshore accounts, secret name accounts, and shell companies called private investment corporations. These private investment corporations, or PICs, are designed for the purpose of holding and hiding a person’s assets. The assets could be real property, money, stock, art, or other valuables. The nominal officers, trustees, and shareholders of these shell corporations are often themselves shell corporations controlled by the private bank. The PIC then becomes the holder of the various bank and investment accounts, and the ownership of the private bank’s client is buried in the records of so-called secrecy jurisdictions, such as the Cayman Islands.

“Private banks keep prepackaged PICs on the shelf, awaiting activation when a private bank client wants one. Shell companies in secrecy jurisdictions managed by shell corporations which serve as directors, officers, and shareholders—shells within shells within shells, like Russian Matryoshka dolls, which in the end can become impenetrable to legal process. Private bankers specialize in secrecy. Even if a client doesn’t ask for secrecy, a private banker often encourages it.

“In the brochure for Citibank’s Private Bank on their international trust services, in the table of contents, it lists the attractiveness of secrecy jurisdictions this way: ‘The Bahamas, the Cayman Islands, Jersey, and Switzerland, the best of all worlds.’ This brochure also advertises the advantages of using a PIC. One advantage it lists is this one: ‘PIC assets are registered in the name of the PIC, and your ownership of the PIC need not appear in any public registry.’ Secrecy is such a priority that private bankers have at times been told by their superiors not to keep any record in the United States disclosing who owns the offshore PIC established by the private bank.”

The second thing you need to know about Citigroup is that it is currently under investigation by the Justice Department for questionable money-laundering controls at its Banamex USA unit.

The final thing you need to know is that instead of yanking the bank charter from this serially malfeasant corporation, the U.S. government provided Citigroup with the largest taxpayer bailout in the history of modern finance after it collapsed under the weight of its own hubris in 2008.

According to Citigroup’s own 10K filing with the SEC for 2008, this is the extent to which the U.S. government went to prop up this bank:

“During 2008, the Company benefited from substantial U.S. government financial involvement, including (i) raising an aggregate $45 billion in capital [from the] U.S. Department of the Treasury (UST), (ii) entering into a loss-sharing agreement with various U.S. government entities covering $301 billion of Company assets, and (iii) issuing $5.75 billion of senior unsecured debt guaranteed by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) (in addition to $26.0 billion of commercial paper and interbank deposits of Citigroup’s subsidiaries guaranteed by the FDIC outstanding as of December 31, 2008)…”

This was the part of the bailout the public was allowed to see at the time. What the public could not see initially was the more than $2 trillion in cumulative, below-market rate, emergency loans that the Federal Reserve was making to Citigroup from 2008 to at least 2010 to keep it from sinking. The Fed fought a multi-year court battle to keep that information secret, losing at both the District and Appellate Court.

Back in 2006, Citigroup reported this list of more than 1600 subsidiaries with over five dozen companies located in secrecy jurisdictions like the Cayman Islands, Jersey and Luxembourg. As Citigroup has fallen under increasing scrutiny from the Justice Department, the list of subsidiaries that it is officially reporting to the SEC has been whittled down dramatically.

How did the Miami office of Citigroup become involved with companies connected to Mossack Fonseca, the law firm causing an uproar around the globe? The Miami Herald, owned by McClatchy newspapers, which has been participating in the Panama Papers investigation since the beginning, offers one possible link.

On April 4 of this year, Nicholas Nehamas reported at the Miami Herald that Olga Santini is the “Miami representative for Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca,” working out of a condo at the Palace on Brickell Avenue in Miami. We measured the distance from that condo to the Citigroup building. It’s 1.2 miles.

Nehamas writes further:

“Hundreds of shell companies — many of them registered in the British Virgin Islands and other jurisdictions that profit by allowing corporate owners to hide their names — can be traced back to Santini’s condo.

“The leaked records offer little evidence that Santini and MF questioned the backgrounds or business activities of people who wanted offshore companies — what the industry calls due diligence…

“Many of the people coming to Santini and her firm were Brazilian politicians, judges and politically connected businessmen. Several had been accused of corruption — but were still able to set up offshores through Mossack Fonseca.

“Others who benefited from the firm’s services were later charged with criminal activity, often allegedly carried out through their MF offshores.”

The Citigroup ties to the Panama Papers is more bad news for Hillary and Bill Clinton, whose political and charitable careers have been infused with Citigroup money. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, Citigroup ranks second for lifetime contributions to Hillary’s political campaigns. Citigroup has also committed $5.5 million to the Clinton Global Initiative, part of a charity run by the Clintons. According to PolitiFact, Citigroup provided a $1.995 million mortgage to allow the Clintons to buy their Washington, D.C. residence in 2000 – a time when Hillary Clinton says they were “dead broke.”

What has Citigroup’s money bought in return in Washington? Senator Elizabeth Warren recapped Citigroup’s outsized influence during the 2014 Senate confirmation hearing of Stanley Fischer for Vice Chairman of the Federal Reserve. (Fischer was another high-paid former employee of Citigroup, as is the current U.S. Treasury Secretary, Jack Lew, whose Citigroup past included an offshore account and a $940,000 bonus for getting a job in the Federal government, a condition of his employment agreement.) Senator Warren stated to Fischer at the hearing:

“Many big banks are well represented in Washington but the connection between Citigroup and Democratic administrations really sticks out. Three of the last four Democratic Treasury Secretaries have Citigroup ties; the fourth was offered but turned down the CEO position at Citigroup. Former Directors of the National Economic Council and the Office of Management and Budget at the White House and our current U.S. Trade Representative also have Citigroup ties. You once served as President of Citigroup International and are now in line to be number two at the Federal Reserve…”

As voters head to the final primaries to choose between Hillary Clinton and Senator Bernie Sanders to be the Democratic Presidential candidate in November, the relationship between the Clintons and Citigroup might well be worthy of factoring into the debate.