By Pam Martens: November 13, 2014

On November 6, Bloomberg News reporter, Matthew Boesler, set off a flurry of comments with an article headlined: “Fed Concern With Repeat of 1937 Blunder Echoed by Markets.”

The reference to 1937 relates to the fact that as the U.S. economy was showing signs of improvement from the conditions of the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Federal government and the Federal Reserve overreacted to inflationary concerns with contractive measures in 1937, sending the economy into a sharp slump in late 1937 and 1938.

The chief worrier at the Fed about it making the same mistake today is Charles Evans, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Evans’ background is that of a long-term researcher. Prior to becoming President of the Chicago Fed, he served as its Director of Research, and earlier, its Senior Economist in charge of the Macroeconomics Research Group.

In four speeches beginning on September 24, Evans has been effectively telling Fed Chair Janet Yellen and the Federal Open Market Committee of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors not to crash the economy again by ignoring the lessons of 1937 and 1938. Evans’ most pointed warnings came in the September 24 speech with direct references to 1937:

“Past experience with the zero lower bound also counsels patience. History has not looked kindly on attempts to prematurely remove monetary accommodation from economies that are in or near a liquidity trap. The U.S. experience during the Great Depression — in particular, in 1937 — is a classic example for monetary historians: In response to the positive growth and reinflation that occurred after devaluation and suspension of gold convertibility, the Fed raised reserve requirements, the Treasury sterilized gold inflows, and there was a fiscal contraction. Subsequently, the economy dropped back into recession and deflation. During this time, interest rates remained very low. The discount rate was lower after 1937 than before, and Treasury bill rates were less than 1 percent. By many economic accounts, it took the big fiscal expansion associated with World War II to exit the Great Depression.”

Thanks to the outstanding historical archives on the Great Depression maintained by the St. Louis Fed, we can go back and actually observe exactly what did go wrong in 1937 once the Fed tightened policy. To put it bluntly, the economy fell off a cliff.

The November 1937 Survey of Current Business released by the Commerce Department summed up the stock market fallout as follows:

“In the fluctuations of October 19, industrial, railroad, and utility share prices fell to the lowest points since May 1935. At the bottom of the movement, the New York Times’ index of 50 stocks was down 40 percent from the March high.”

Thanks to the ill-conceived notion of chaining today’s worker and his or her confidence level to the rise and fall of the stock market by replacing corporate pensions with 401(k) plans, a 40 percent drop in the stock market triggered by Fed tightening next year would instantly translate into lowered levels of confidence and consumer spending.

The Federal Reserve Bulletin dated December 1937 shows just how dramatically and precipitously things fell apart:

“The volume of industrial production has declined sharply during the last three months, and the Board’s adjusted index, which, during the first eight months of the year, averaged 116 percent of the 1923-1925 average, is expected to be below 95 for November…

“Output of nondurable manufactures declined by about 15 percent from the spring of this year to October…

“Iron and steel production has shown the most pronounced decline. Activity in this industry, which in the first half of the year was the greatest since 1929, has decreased steadily since August and at the end of November output of steel ingots was estimated at 30 percent of capacity, as compared with an average rate of 85 percent in August…”

On September 24, 2014, the same day that Chicago Fed President Charles Evans was delivering his sobering speech on parallels to 1937, Wall Street On Parade reported the following:

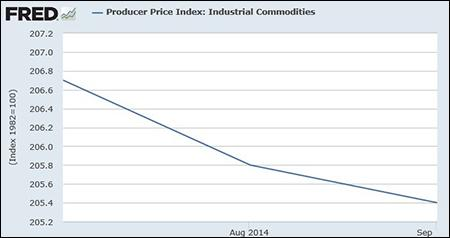

“The serious downward draft in commodity prices is also flashing another warning signal. Deflating commodity prices are not compatible with a global economic growth story that would sustain a legitimate bull market in corporate stock prices.

“Iron ore has now slumped 41 percent this year, marking a five-year low. In just the third quarter the price is off by 15 percent, suggesting the trend remains in place. This week the price broke $80 a dry ton for the first time since 2009.

“Agricultural commodity prices are also confirming the trend with corn off 22 percent since June and wheat down 16 percent in the same period. Soybean prices are down 28 percent this year to the lowest in four years.

“Deflationary winds blowing in from Europe, cooling economic growth in China, together with the question of just how disfigured the stock market has become as a result of $1.09 trillion propping up the S&P 500 through corporate buybacks in the last 18 months, all signal one word for the average investor: caution.”

This morning, the price of Brent crude oil is trading below $80 per barrel, a fresh four-year low with no bottom in sight.

The Fed has already been effectively tightening by cutting back its bond purchases (QE-3) since January and ended further purchases last month on the basis that the economy is improving. It has also signaled that it believes the economy will be strong enough to hike rates at some point next year.

But if you look at the declining yields on U.S. Treasury notes that have accompanied the Fed’s tapering and the decline in commodity prices, what the markets are telling the Fed is that it may already be too late to avert another 1937-style slump.