By Pam Martens: March 22, 2013

One year ago this week, Ina Drew, head of the Chief Investment Office at JPMorgan which oversaw the synthetic credit derivatives portfolio that eventually blew up $6.2 billion of depositors’ money, told her traders “phones down,” signaling that she was halting all trading in those instruments. What Drew should have much earlier told her traders was: “unplug algorithms; plug in brains.”

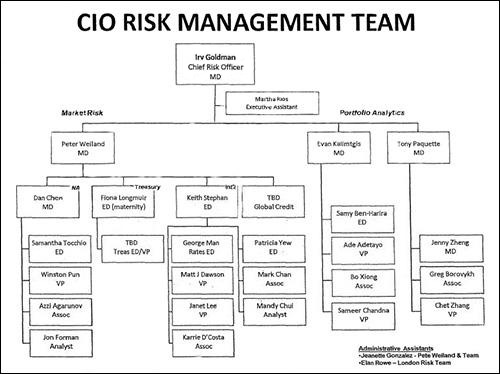

Despite a multitude of formulas for measuring risk, multiple layers of oversight management, 28 members of a risk management team with titles like Managing Director, Executive Director, and Vice President, it somehow didn’t occur to any of these folks that the number one criteria for a trading investment is that you need to be able to get out of it.

London Whale was the nickname given to the JPMorgan trader, Bruno Iksil, as a result of the outsized bets he was making on one particular illiquid credit default swap index known as the 10-year Markit CDX North America Investment Grade Index Series 9 or in trader lingo, the IG9. Throughout the documents released by the Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations are references to the traders needing to “defend our position.”

What “defend our position” actually meant was: we need to get more exposure to this losing trade to prop up the price of the losing trade so that when we price the total position (mark to market) we won’t have even bigger losses to show our bosses. An “unplug algorithms; plug in brains” analysis of this theory for managing depositors’ life savings is: we will be taking on more risk in the position we can’t get out of so that we really, really can’t get out of it.

One of the first, inviolate rules that a rookie stockbroker learns is “cut your losses short.” Also expressed as “don’t get married to the trade.” The JPMorgan traders broke the most basic of all investment rules and the easiest one to understand. The purpose of cutting losses short is to “defend the principal” so that it will be there to participate in profit-making trades in the future. “Defend our position” was an exercise of “defend our ego”; refusing to admit that what the traders originally thought was a brilliant trading strategy was now a position capable of losing $415 million in just one day and $6.2 billion (that we know of) in the aggregate. JPMorgan has stopped reporting losses on the position.

So what can the average American learn from this. One overarching message is to understand what is and is not a liquid investment and how to align one’s liquidity needs with appropriate investments.

For example, let’s say an individual has $25,000 to invest but will need it in 3 years for a child’s college tuition and can’t afford to lose any of this money. Appropriate investments would be a 3-year FDIC insured Certificate of Deposit or a U.S. Treasury security maturing in 3 years. If the individual has no other liquid funds for an emergency event, an appropriate amount of the $25,000 should remain in a liquid, insured money market account.

An investment strategy similar to what was done at JPMorgan would be to take the full $25,000 and use it as a down payment on a home for flipping in 3 years in an area of heavy foreclosures.

When JPMorgan’s Chairman and CEO, Jamie Dimon, testified before Congress last year, he said that JPMorgan makes loans to some of the biggest corporations in the world. As a result, it needs to maintain liquidity because at any time a large corporation could ask for a huge loan. Given that reality, what happened in the Chief Investment Office makes even less sense.

JPMorgan's Risk Management Team for the Chief Investment Office. Released by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee On Investigations

Pam Martens, the Editor of Wall Street On Parade, managed the life savings of average Americans for 21 years on Wall Street. Her personal finance columns seek to help the public better understand the jargon, complexities, and conflicts of Wall Street. The information that appears on this site cannot, and does not, take into account your particular investment goals, your unique financial situation or income needs and is not intended to be recommendations appropriate for you. When it comes to making your own investment decisions, you should always consult in advance with your financial advisor and accountant.

At times, Wall Street On Parade links to news or opinion on other sites which we believe to be in the public interest. These web sites may also contain investment advice or investment advertising. We receive no remuneration for these links, provide them purely in the public interest, and are not endorsing or recommending any investment information that may appear on the site.