By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: June 27, 2018 ~

Despite President Donald Trump’s leanings toward authoritarianism, he is likely to learn a hard truth this year and next – that the Federal Reserve can make or break his presidency by delivering up to three different gut punches to the markets, which are very likely to spill over into the economy. And without a good economy, even Trump’s most fervent supporters may begin to doubt his omnipotence.

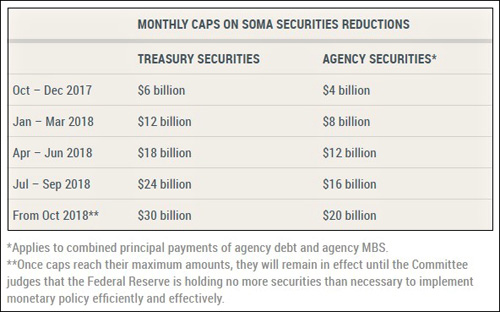

For starters, next Monday the Federal Reserve is scheduled to shrink its purchases of U.S. Treasury securities and Federal agency debt and mortgage-backed securities by another $10 billion a month, from a shrinkage of $30 billion to $40 billion. And by October 1 of this year, the Fed will move from draining $40 billion a month from the markets to draining $50 billion, according to its previously announced schedule. (See chart below.) At the rate of $50 billion a month, that’s $600 billion less in market accommodation from the Fed.

The Fed policy is part of its so-called normalization process to move away from the actions it took to stave off a collapse of the financial system as Wall Street banks cratered in 2008. As a result of its massive bond buying programs known as Quantitative Easing (QE1, QE2 and QE3) the Fed’s balance sheet swelled from $914.8 billion at the end of 2007 to $4.5 trillion in 2014. Its unwinding of its bond-buying program, which began in October 2017, has yet to make much of a dent in reducing its balance sheet, which stood at $4.393 trillion as of its financial report for February 28, 2018.

During his press conference on June 13, the new Fed Chair Jerome Powell mentioned the normalization schedule, stating: “…our program for reducing our balance sheet, which began in October, is proceeding smoothly. Barring a material and unexpected weakening in the outlook, this program will proceed on schedule, and our balance sheet will continue to shrink.”

Powell also mentioned during the press conference how close the U.S. had come to a complete financial meltdown in 2008. He stated:

“…and if I can just take this opportunity to say, you know, the financial system all but failed 10 years ago. We went to work for 10 years to strengthen it—stronger capital, stronger liquidity, stress testing, resolution planning. We want to keep all that stuff. We want to make it, you know, even more effective and certainly more efficient. We want to tailor those regulations for institutions. We want the strongest provisions to apply to the most systemically important institutions. And so we’re committed to preserving and enhancing that structure.”

Unfortunately for Powell, the most systemically important institutions are the big Wall Street banks like JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America and Morgan Stanley who are collectively sitting on hundreds of trillions of dollars in derivatives – a good chunk of which are the credit default swaps that played a major role in bringing down the financial system in 2008. The Fed will announce tomorrow whether it is going to allow these banks (and others) to continue to bleed cash (or take on more debt) through massive stock buybacks and dividend boosts for shareholders. The annual announcement is known as the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) and is the second leg of the Fed’s stress testing process for banks.

Stock buybacks by the mega banks have come under intense criticism. On July 31 of last year, Thomas Hoenig, the Vice Chair of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) that backstops with Federal insurance the trillions of dollars in deposits held by these mega banks, sent a warning letter about buybacks to the Chair and Ranking Member of the U.S. Senate Banking Committee.

Hoenig stated in his letter that the ten largest banks in the country “will distribute, in aggregate, 99 percent of their net income on an annualized basis,” by buying back excessive amounts of their own stock and paying dividends to their shareholders. Hoenig said that if those 10 banks had retained a larger share of the earnings they earmarked for dividends and share buybacks in 2017, they would have been able “to increase loans by more than $1 trillion, which is greater than 5 percent of annual U.S. GDP.”

Earlier this month, Washington Post business and economics columnist Steven Pearlstein wrote a detailed article on the role that stock buybacks is playing in retarding future economic growth in the U.S. as well as contributing to the next debt implosion, since a large part of the buybacks are financed with debt. Pearlstein said the end result is that “Corporate America, in effect, has transformed itself into one giant leveraged buyout.”

Another alarm bell on buybacks was sounded this month by Robert J. Jackson, Jr., a recently appointed SEC Commissioner who filled an empty Democratic seat on the SEC. Speaking at the Center for American Progress, Jackson warned that “there is clear evidence that a substantial number of corporate executives today use buybacks as a chance to cash out the shares of the company they received as executive pay,” adding that “in the years leading up to the financial crisis, top executives at Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers personally cashed out $2.4 billion in stock before the firms collapsed.” Jackson provided the data to back up his current assertions.

We’ll find out tomorrow if the Fed will rein in this dodgy practice of stock buybacks at the big banks (potential gut punch number two) or if it will continue the laissez-faire practices of former Fed Chair Janet Yellen.

Gut punch number three would come from further rate hikes by the Fed. Thus far, the Fed has raised rates seven times since the first rate hike on December 16, 2015. At his June 13 press conference, which included the announcement of another ¼ point rate hike, Powell took a question from Associated Press Economics Writer Martin Crutsinger. The exchange went like this:

CRUTSINGER: Marty Crutsinger, Associated Press. At this meeting, you hiked your — the funds rate, you changed the dot plot to move from 3 to 4 for this year, and you took out a sentence that you’d been using for years about how long rates might stay low. But you say that none of this signals a change in policy views. But shouldn’t we see from this combination of things that the Fed is moving to tighter policy?

POWELL: I think what you should see is that the economy is continuing to make progress. The economy has strengthened so much since I joined the Fed, you know, in 2012 and even over the last couple of years. The economy is in a very different place. We — unemployment was 10 percent at the height of the crisis. It’s 3.8 percent now and moving lower. So really what you — the decision you see today is another sign that the U.S. economy is in great shape. Growth is strong, labor markets are strong, inflation is close to target, and that’s what you’re seeing. For many years, as I mentioned — many years — we had interest rates held low to support economic activity. And it’s been clear that as we’ve gotten closer to our statutory goals, we should normalize policy, and that’s really what we’ve been consistently doing for some years now.

Translation: there’s no better time than the present to continue rate hikes so that when the next economic downturn hits we’ll be at an adequate level of interest rates in order to deploy rate cuts to stimulate the economy.