By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: May 9, 2018 ~

Three years ago this month the U.S. Department of Justice brought felony charges against two of the largest Wall Street banks, JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup, for their involvement in rigging foreign currency markets. On the same date, two foreign banks, Barclays PLC and the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), were charged with felonies in the same matter. A fifth bank, UBS, was charged with a felony for its role in rigging the interest rate benchmark known as Libor. All five banks pleaded guilty to the charges.

Three years ago this month the U.S. Department of Justice brought felony charges against two of the largest Wall Street banks, JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup, for their involvement in rigging foreign currency markets. On the same date, two foreign banks, Barclays PLC and the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), were charged with felonies in the same matter. A fifth bank, UBS, was charged with a felony for its role in rigging the interest rate benchmark known as Libor. All five banks pleaded guilty to the charges.

Citigroup was fined $925 million by the Justice Department for its foreign currency conduct that ran from as early as December 2007 until at least January 2013, roughly five years. JPMorgan was fined $550 million for rigging activity that ran from as early as July 2010 to January 2013, about two and a half years. The offenses the banks were charged with pertained to their foreign currency traders engaging in chat rooms with traders from competitor banks, sharing confidential customer order information in order to rig foreign currency markets and boost profits for their firms.

Somehow, Goldman Sachs slipped through the Justice Department’s net. It was never charged with a felony by the Justice Department. Now, three years later, the Federal Reserve and the New York State Department of Financial Services (DFS) have imposed a combined modest fine of $109.5 million against Goldman Sachs for essentially the very same conduct that resulted in Citigroup and JPMorgan Chase becoming felons and paying much steeper fines.

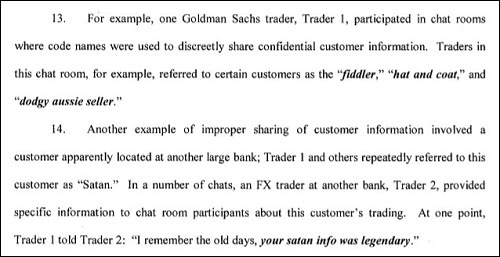

The Fed’s consent order with Goldman Sachs is slim on details but the DFS consent order describes dozens of instances where Goldman traders shared customer information and/or overtly attempted to manipulate the foreign currency market over a period of about 5 years from 2008 to early 2013. (Read the explicit examples here.)

The press release from the DFS sounds extremely similar to the charges leveled by the Justice Department against Citigroup and JPMorgan on May 20, 2015. The DFS stated:

“The DFS investigation found that from 2008 to early 2013, Goldman foreign exchange traders participated in multi-party electronic chat rooms, where traders, sometimes using code names to discreetly share confidential customer information, discussed potentially coordinating trading activity and other efforts that could improperly affect currency prices or disadvantage customers. This improper activity sought to enable banks and the involved traders to achieve higher profits from execution of foreign exchange trades, sometimes at customers’ expense…

“Although a senior member of Goldman Sachs’ Global Foreign Exchange Sales Division raised concerns about the sharing of customer information, there is no evidence the supervisor took any steps to escalate to Goldman Sachs’ compliance function any of these serious concerns.”

Why was the foreign exchange case against Goldman relegated to the Federal Reserve (the U.S. central bank that is known for its coziness with Wall Street) and the DFS, a state agency, instead of being handled by the Justice Department’s criminal enforcement division that has the power to level felonies? This is just one more of those mysteries that habitually enshrine a fog around the meting out of justice on Wall Street. But there is one previous case that comes to mind where Goldman Sachs made out very well under the Kindly Uncle treatment of the Federal Reserve.

Carmen Segarra was a bank examiner with a law degree at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Segarra charged in a Federal lawsuit filed in October 2013 that she was told to change her negative examination of Goldman Sachs by her colleagues at the New York Fed, who she says also obstructed and interfered with her investigation. When Segarra refused to alter her findings, she was terminated in retaliation and escorted from the Fed premises according to her lawsuit. The folks telling her to change her opinion at the New York Fed are called “relationship managers.” They manage the “relationships” with big, powerful Wall Street firms like Goldman Sachs who are called “primary dealers.” This is how the New York Fed explains its interactions with “primary dealers”:

“Primary dealers serve as trading counterparties of the New York Fed in its implementation of monetary policy. This role includes the obligations to: (i) participate consistently in open market operations to carry out U.S. monetary policy pursuant to the direction of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC); and (ii) provide the New York Fed’s trading desk with market information and analysis helpful in the formulation and implementation of monetary policy. Primary dealers are also required to participate in all auctions of U.S. government debt and to make reasonable markets for the New York Fed when it transacts on behalf of its foreign official account-holders.”

That sounds like a very incestuous relationship for an entity that is also a Wall Street bank regulator and bank examiner.

Segarra’s Federal lawsuit was filed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. Her Judge was Ronnie Abrams, wife of Greg Andres, a partner at law firm Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP. The case was before the court from October 2013 until April 3, 2014 when Judge Abrams scheduled a telephone conference with both sides to advise that “it had just come to her attention that her husband…was representing Goldman Sachs in an advisory capacity.”

Neither side asked for the Judge’s recusal at this point but a week later Segarra’s attorney, Linda Stengle, asked for “a more complete disclosure of both Judge Abrams’s husband’s relationship with Goldman Sachs and Judge Abrams’s prior working relationship with defense attorney Thomas Noone.” (Noone was the lawyer representing the New York Fed). Stengle wanted the “commencement date of Husband’s present work for Goldman Sachs” and “historical relationship, if any, between Husband and Goldman Sachs.”

According to footnotes in the decision, Noone, the attorney for the New York Fed, also previously worked for the Davis Polk & Wardwell law firm, as did the Judge previously.

Less than three weeks after the Judge revealed her husband’s advisory work for Goldman Sachs, she threw out Segarra’s case while refusing to provide any further details on her husband’s involvement with Goldman Sachs. What she did instead was an eye-opener: Judge Abrams attempted to tar the reputation of Segarra’s attorney, accusing her of “judge-shopping” when all she had actually done was to ask for a modicum of transparency.

At the time this all went down at the Fed, William (Bill) Dudley was its President. (Dudley is set to retire from the New York Fed on June 17.) Prior to joining the Fed, Dudley worked at Goldman Sachs from 1986 to 2007 in senior positions.