By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: June 25, 2015

Remember when the Department of Homeland Security was issuing those color-coded terrorist alerts? Well, they don’t do that anymore. They’re back to using plain ole black-and-white words to describe threats.

Remember when the Department of Homeland Security was issuing those color-coded terrorist alerts? Well, they don’t do that anymore. They’re back to using plain ole black-and-white words to describe threats.

Apparently, however, the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Financial Research (OFR) thought it was such a cool idea that they’ve started color-coding threats to our financial security from the denizens on Wall Street: the gang that brought our country to its knees in 2008 while the most expensive military in the world was hunting down robed cave-dwellers in the Middle East.

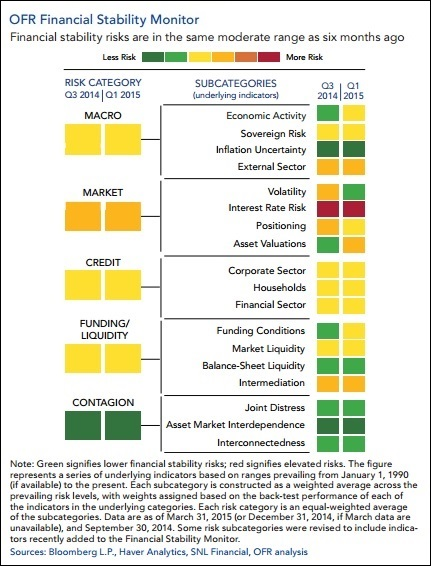

OFR’s color-threat alert is called the Financial Stability Monitor. The monitor is based on approximately 60 indicators and organized as a heat map: The closer an indicator is to the red end, the more elevated the risks; the closer an indicator is to the green end of the spectrum, the lower the risks. The Monitor, released yesterday, says that “financial stability risks remain moderate.” Unfortunately, when we studied the accompanying chart, we found that it’s based on first quarter data, meaning it’s almost three months old. (Imagine Homeland Security issuing a terrorist alert, then telling you it might not be all that reliable because it’s based on stale intelligence.)

Nonetheless, there’s some very interesting takeaways from the Monitor. First, even though the OFR has characterized the financial stability threat as “moderate,” a close reading of the report suggests a heightened threat. These are some key points from the report:

- Financial and economic risks have further decoupled, with financial risk-taking occurring against the backdrop of a tepid growth recovery.

- Global monetary policies and economic growth continue to diverge. Central banks in some advanced economies, led by the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan, are conducting highly expansionary monetary policies, while in the United States, the Federal Reserve is closer to embarking on a tightening cycle.

- Foreign risks have increased, including intensified government financing risks in Greece and weakening economic fundamentals in key emerging markets.

- After a lengthy period of unusually low yields, long-term government bond yields in advanced economies have risen abruptly since April. The speed and volatility of the correction have been significant, demonstrating the fragility of market liquidity and the vulnerability of markets to shocks during periods of low volatility and extended bond duration…

- Although low volatility previously contributed to excessive risk-taking, the recent increase in volatility has not been accompanied by a proportionate decline in risk-taking.

- The migration of risks from banks to less-regulated sectors is a continuing concern. For example, non-bank institutions continue to increase their share of highly leveraged syndicated loans.

- Some market liquidity measures — the ability of market participants to sell assets with limited price impact and low transaction costs — signal a deterioration in liquidity. These changes have occurred along with a decline in the provision of liquidity by primary dealers, which could potentially reduce their willingness to buffer intense selling pressure.

Reduced liquidity, migration of risks from banks to less-regulated sectors, and rising interest rates sound to us like the perfect financial storm potentially in the making.

Indeed, the one area flashing red on the chart is interest rate risk. Gary Cohn, President and COO of Goldman Sachs, took to the radio last week to share his two cents on what’s likely to happen when the Federal Reserve finally hikes interest rates (after talking about it since what feels like the Paleozoic era).

Jake Siewert, global head of Corporate Communications at Goldman Sachs asks Cohn, in regard to a Fed rate hike: “Do you think markets have fully priced in the risks?” Cohn responds:

“We’re probably less ready than people think. It always is uniquely interesting how it comes as a surprise to everyone when something happens that we’ve been talking about for a long period of time…The reality of something happening is always different than the dialogue of it’s obviously going to happen. And when it does happen, it’s usually not the first derivative event that people are caught off guard by. They’re caught off guard by the second, third and fourth derivative events.”

We believe Cohn is referring to exogenous events as opposed to actual derivatives like credit default swaps. But, of course, derivatives do have a nasty habit of blowing up at inopportune times.

One area of significant financial risk to the U.S. financial system which the OFR can’t color-code because it’s hiding in a black hole is the capital relief trades that major U.S. banks and their foreign counterparts are conducting with unknown counterparties that could, potentially, teeter under market stresses caused by a Fed interest rate hike or simply rising rates.

As we reported last week, these so-called capital relief trades are being conducted by the banks, with hedge funds and private equity funds as counterparties, to dress up the appearance of stronger capital while keeping the deteriorating assets on their books. On June 11, OFR released a report on these trades, noting: “Banks have significant incentives to reduce their required regulatory capital by transferring credit risk to third parties. But public data needed to analyze such activities are scant.”

If we can’t quantify the amount of these trades; if we have no transparency on the credit-worthiness of the counterparties, is OFR really on solid ground with its color-coded warnings?

When it comes to Wall Street, without the restraint imposed by the repealed Glass-Steagall Act, it’s always a red alert day for investors.