By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: September 10, 2014

Sparks were flying yesterday in what is typically a snooze-worthy Senate session. It felt like alien body snatchers had decided to remove the zombies and return the real U.S. Senators to their chairs on the Senate Banking Committee. Senators, right and left, asked tough, probing questions of the nation’s banking regulators, leaving many squirming in their chairs.

The session was so unusual that Senator Elizabeth Warren, a Democrat from Massachusetts, and Senator Richard Shelby, a Republican from Alabama, closed out the session in complete agreement that there is something seriously broken about the justice system in America.

Senator Warren told the hearing that in the past year, three of the nation’s largest banks — JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup and Bank of America — have admitted breaking the law and settled the claims for $35 billion. The Senator continued:

“As Judge Rakoff of the Southern District of New York has noted, the law on this is clear. No corporation can break the law unless an individual within that corporation broke the law. Yet, despite the misconduct at these banks that generated tens of billions of dollars in settlement payments by the companies, not a single senior executive at these banks has been criminally prosecuted. Now, I know that your agencies can’t bring prosecutions directly, but you’re supposed to refer cases to the Justice Department when you think individuals should be prosecuted. So, can you tell me how many senior executives at these three banks you have referred to the Justice Department for prosecution?”

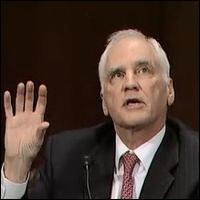

Federal Reserve Governor Daniel Tarullo Has No Knowledge About Whether the Fed Has Made a Single Criminal Referral to the Justice Department

Fed Governor Daniel Tarullo said he didn’t know the answer to the question. Senator Warren leaned forward in her chair to stare at Tarullo, incredulous at his answer. Warren then described the stark difference between this era and what happened after the savings and loan crisis, stating:

“After the savings and loan crisis in the 1970s and 1980s, the government brought over a thousand criminal prosecutions and got over 800 convictions. The FBI opened nearly 5,500 criminal investigations because of referrals from banking investigators and regulators.”

Warren, a former Harvard Law School professor, continued:

“The main reason we punish illegal behavior is for deterrence; to make sure that the next banker who’s thinking about breaking the law remembers that a guy down the hall was hauled out of here in handcuffs when he did that. These civil settlements don’t provide deterrence. The shareholders for the company pay the settlement; senior management doesn’t pay a dime. And, in fact, if you’re like Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JPMorgan Chase, you might even get an $8.5 million raise for negotiating such a great settlement when your company breaks the law. So, without criminal prosecution, the message to every Wall Street banker is loud and clear: if you break the law you are not going to jail, but you might end up with a much bigger paycheck. No one should be above the law. If you steal a hundred bucks on Main Street, you’re probably going to jail. If you steal a billion bucks on Wall Street, you darn well better go to jail too.”

When Senator Richard Shelby’s turn to speak came next, a former prosecutor himself in Alabama, he picked up on the same thread, stating:

“I realize that you’re regulators. You’re not prosecutors. But if there’s $35 billion more or less in fines and settlements because of criminal conduct, and there’s no justice – justice is important for the big and the small. Something’s wrong with the justice department. People shouldn’t be able – whoever they are, not just financial institutions – shouldn’t be able to buy their way out for culpability, especially when it’s so strong it defies rationality. I agree with her [Warren] on that.”

Senator Chuck Schumer, Democrat from New York, was livid over the Fed’s nonsensical move last week to move corporate bonds into the category of “high quality liquid assets” for big banks to hold on their balance sheets in case of emergency liquidity needs while dumping municipal bonds from the category. (Every rookie broker in America is taught as part of his licensing exam that direct obligations of the states are second in safety only to issues of the U.S. government – because both are backed by taxing authority. Why rookie brokers know more than Federal regulators is cause for concern.)

Schumer told the regulators:

“By excluding municipal bonds from being considered high quality liquid assets, Federal regulators have run the risk of limiting the scope of financial institutions willing to take on investment grade municipal securities, which we know are the life blood of development in this country. My city and state, New York City and state, rely on this financing to pave roads, bridges and start construction in new schools. But it’s not just New York. Any city or state that has made tough decisions to protect their credit ratings – Chicago, Philadelphia, California – are susceptible to the impact of this rule.”

Schumer went on to cite examples from the last crisis in 2008 and 2009, stating:

“I’ve not yet heard a convincing argument why, for instance, corporate debt can be considered a high quality liquid asset but investment grade municipal securities cannot. Investment grade municipal bonds have comparable — if not better — trade, volume and price volatility and they performed well through the financial crisis. In fact, in 2008 and 2009, price declines on triple-A corporate bonds were greater than the price declines on both double-A general obligation bonds and revenue bonds.”

Schumer said mayors, finance directors and governors were “howling” about this rule and he asked the regulators if they were reconsidering including municipal bonds. Tarullo said the Fed was looking at the issue right now and some categories of municipal bonds might be added based on the outcome of their studies.

Senator Robert Menendez, Democrat of New Jersey, grilled SEC Chair Mary Jo White on why she hasn’t taken any action on forcing corporations to reveal their campaign spending. Menendez said:

“This summer, the SEC received its record one-millionth public comment supporting a rule to require public issuer companies to disclose their political campaign spending to investors. Supporters include leading academics in the field of corporate governance, Vanguard founder John Bogle, investment managers and advisors and the investing public. Without disclosure, corporate insiders may be spending company funds to support candidates or causes that are directly adverse to shareholders’ interests, without shareholders having any knowledge of it.”

SEC Chair White said the SEC was focused on rulemaking in the area of Dodd-Frank and the Jobs Act and had no current plans to address rules on campaign spending on the part of corporations.

Menendez countered that the Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United “which opened the floodgates for corporate election spending” presumed that shareholders would have transparency in order to enforce accountability over executives. Menendez asked how shareholders could have transparency if they can’t even get basic information about what is being spent.