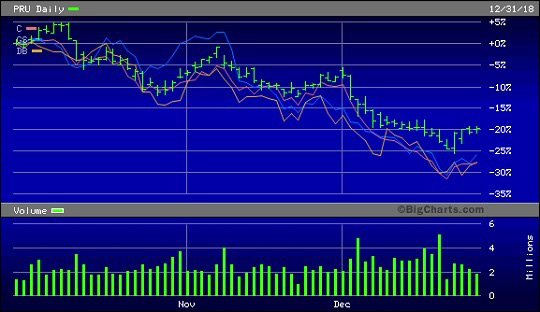

Prudential Financial Traded as a Clone to the Big Wall Street Banks from October to December of Last Year. Prudential, green line, versus Citi, Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank.

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: June 3, 2019 ~

U.S. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin (a/k/a the former foreclosure king) has been attempting to dismantle regulatory restraints on Wall Street’s worst instincts since he took office. Making Mnuchin even more dangerous is the fact that, under statute, he simultaneously sits as head of the Financial Stability Oversight Council (F-SOC) even as he appears to be attempting to undermine financial stability in the U.S.

One of Mnuchin’s most alarming actions on behalf of F-SOC came last October 17 when the Council announced that it was removing the designation of Prudential Financial as a SIFI – a Systemically Important Financial Institution that required enhanced supervision and prudential standards. Mnuchin stated at the time: “The Council’s decision today follows extensive engagement with the company and a detailed analysis showing that there is not a significant risk that the company could pose a threat to financial stability.”

The chart above shows what happened to Prudential from the date of Mnuchin’s statement to the end of 2018. Its stock started sinking like a rock in a pattern that was so close to the trading pattern of Citigroup, Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank that they could have been clones of one another. What does Prudential have in common with those three banks? Like them, it’s a major derivatives counterparty and on the hook for billions of dollars if derivatives blow up Wall Street again as they did in 2008.

Jeremy Kress, an Assistant Professor of business law at the University of Michigan Ross School of Business and a former attorney in the Banking Regulation & Policy Group of the Federal Reserve, had warned against taking this action in March of 2018. Writing for the American Banker, Kress explained that while other SIFIs that had been removed from the list (AIG, GE Capital and Met Life) had taken steps to shrink their systemic footprint, Prudential had actually grown larger and more systemic. Kress wrote:

“…Prudential has grown by more than $100 billion since its designation. Meanwhile, Prudential’s interconnectedness with other financial companies has increased: Its notional derivatives exposures and repurchase agreements have each swelled by more than 30% since its designation. In sum, Prudential’s financial data certainly do not suggest that it has become less systemically important…”

Kress followed his article in the American Banker with a more detailed paper in the Stanford Law Review in December of 2018, after FSOC’s formal action was taken. He detailed further how Prudential had become even more dangerous since its original SIFI designation, writing:

“Prudential increased its asset size and its involvement in risky activities like repurchase agreements, securities lending, and derivatives. Prudential apparently calculated that it could escape its SIFI label simply by waiting until deregulatory policymakers controlled FSOC.”

Kress also explained where Prudential ranked in terms of its systemic footprint:

“FSOC not only relies on misleading empirical analyses, it also inappropriately disregards well-respected metrics of Prudential’s systemic importance. For example, Prudential ranks third among all U.S. financial companies in SRISK, one of the most commonly cited measures of a firm’s systemic footprint. SRISK measures a firm’s expected capital shortfall given a severe market decline, based on its size, leverage, and risk. Prudential’s SRISK is roughly comparable to Morgan Stanley’s, and it ranks behind only Citigroup’s and Goldman Sachs’.”

But Mnuchin wasn’t done greasing the wheels for the next train wreck on Wall Street. On March 13 of this year, F-SOC proposed a complete rewrite of rules governing how a financial institution might find itself designated as systemically important and subject to heightened supervision. In vague language, Mnuchin and F-SOC proposed to focus all decisions going forward on an “activities-based approach,” writing as follows:

“The Dodd-Frank Act gives the Council broad discretion to determine how to respond to potential threats to U.S. financial stability. As part of its activities-based approach, the Council will examine a diverse range of financial products, activities, and practices that could pose risks to financial stability. The types of activities the Council will evaluate are often identified in the Council’s annual reports, and include activities related to the extension of credit, maturity and liquidity transformation, market making and trading, and other key functions critical to support the functioning of financial markets.”

The proposal was so off-the-wall that the two former Federal Reserve Chairs, Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen, and the two former U.S. Treasury Secretaries, Tim Geithner and Jack Lew, jointly filed a public comment letter comparing the plan to imposing regulatory discipline on a nuclear power plant after it’s entered a nuclear meltdown. The foursome wrote:

“It’s helpful to consider an analogy to nuclear power plants. We certainly don’t impose stringent safety guidelines only on those plants that appear to be on the verge of a meltdown – it doesn’t do much good at that point. Such an event would be catastrophic, so we impose stringent safety guidelines on healthy operations to prevent such a facility from experiencing distress and to ensure that if distress occurs it is manageable. As with nuclear power plants, if we wait until failure is reasonably likely at a firm, it’s too late to do much about it. For this reason, the Dodd-Frank Act clearly requires that we assume the material financial distress of a firm and determine whether a firm in the midst of such distress could pose a threat to financial stability.”

The non-profit watchdog, Better Markets, also filed a public comment letter pointing out the absurdities of the proposal and concluding that it was so “misguided and dangerous” that it should be withdrawn “in its entirety.” Better Markets explained:

“The sum total of the Proposal is that, if it is finalized in its current form, FSOC is unlikely to ever again designate any nonbank financial firm as systemically significant regardless of the systemic threat it actually poses, and that threat, like those posed by AIG, Lehman Brothers, and so many other systemically significant nonbanks, will not be detected or addressed until it is too late. That unacceptable outcome will needlessly increase the likelihood and severity of another devastating financial crisis.”

So who is it that actually benefits from this proposal? The biggest Wall Street banks benefit because they need compromised, or greedy, or gullible counterparties in order to continue to run their cash-cow operations known as derivatives. Wall Street prefers to saddle commercial banks or insurance companies with these derivatives because they typically have good credit ratings, thus allowing the banks to convince their own regulators that they have hedged their risk with a solid counterparty. But as happened with the $185 billion blowup and bailout of the giant insurer AIG during the financial crisis, the systemic dangers were hidden in a little division of AIG called AIG Financial Products, which had escaped regulatory detection until it blew up. More than half of the bailout money that went in the front door of AIG ended up going out the backdoor to the major Wall Street banks and their global counterparts to pay for their derivative bets and securities lending, the very activities that Professor Kress says that Prudential Financial is engaged in currently.

Mnuchin’s history should have disqualified him from being confirmed as U.S. Treasury Secretary – which would have prevented him from sitting atop F-SOC and pushing through his outlandish proposals to deregulate Wall Street. (See Boycotting Mnuchin for Treasury: Democrats Had Strong Grounds.) But Wall Street saw him as an obliging bureaucrat and had their way with Republicans, who voted him into office.

Now, thanks to that vote and the gutting of safeguards on Wall Street, the nation is once again put in financial peril.

Related Articles:

Wall Street Has Placed a Derivatives Noose Around the U.S. Insurance Industry

Wall Street Banks Are Trading as a Herd Because They are Highly Interconnected