By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: February 22, 2016

Fourteen years before Wall Street blew itself up in 2008, the General Accounting Office (now called the Government Accountability Office), warned Congress that Wall Street was on a dangerous path that could put the taxpayer at risk of bailouts as a result of trillions of dollars of derivatives being held by a handful of interconnected firms. These dangers were heightened according to the GAO by shoddy accounting practices for derivatives, inadequate regulatory reporting, and high leverage.

Despite the fact that almost every single warning that the GAO called out in 1994 was ignored by the U.S. Congress, leading to the greatest financial collapse since the Great Depression in 2008, Congress has still not attended to the most dangerous elements highlighted in the report.

Back in 1994, the GAO found that: “U.S. bank regulatory data indicate that the top seven domestic bank derivatives dealers by notional/contract amounts accounted for more than 90 percent of all U.S. bank derivatives activity as of December 1992. SEC data show a similar concentration of activity among U.S. securities derivatives dealers. The top five by notional/contract amounts accounted for about 87 percent of total derivatives activity for all U.S. securities firms as of their fiscal year-end 1992.”

GAO envisioned precisely what transpired in 2008, writing:

“Because the same relatively few major OTC derivatives dealers accounted for a large portion of trading in a number of markets, regulators and market participants feared that the abrupt failure or withdrawal from trading of one of these dealers could undermine stability in several markets simultaneously. This could lead to a chain of market withdrawals, or possibly firm failures, and a systemic crisis.”

GAO also correctly foresaw what happened to AIG in 2008, the big insurance company whose affiliate had sold credit default swaps in the billions of dollars to Wall Street firms and required a $182 billion taxpayer rescue because it could not make good on those swaps, creating a backdoor bailout to firms like Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch and Citigroup. GAO warned in the 1994 report: “Insurance companies’ OTC derivatives affiliates are subject to limited state regulation and have no federal oversight. Yet OTC derivatives affiliates of securities and insurance firms constitute a rapidly growing component of the derivatives markets.”

Rather than defusing the dangers of concentrated risk, the banks and securities firms the GAO was so worried about in 1994 were subsequently allowed to merge (even during the midst of the crisis in 2008) creating ever larger amounts of concentrated risk today. One chart in the GAO study shows that in 1992, Citicorp held derivatives equal to more than 200 percent of its equity capital and loans equal to more than 1200 percent. Citicorp was allowed to merge with Salomon Smith Barney, the investment bank, and Travelers, the insurance company, in 1998 to become Citigroup. During the crash, its stock went to 99 cents a share, requiring the largest taxpayer bailout of a bank in U.S. history.

The same 1992 chart also shows JPMorgan holding over 200 percent of its equity capital in derivatives and over 300 percent in loans. Chase Manhattan was holding over 300 percent of its equity capital in derivatives and over 900 percent in loans. In 2000, Chase bought JPMorgan, becoming JPMorgan Chase. During the crash of 2008, JPMorgan Chase became exponentially more dangerous, taking over the failed Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual.

The GAO report almost perfectly envisioned what was ahead at JPMorgan Chase when it stated: “The issue is one of striking a proper balance between (1) allowing the U.S. financial services industry to grow and innovate and (2) protecting the safety and soundness of the nation’s financial system.”

In 2013, JPMorgan Chase was fined $920 million by four of its regulators for gambling in exotic derivatives in London (London Whale saga) using not its own capital but the deposits of its FDIC-insured bank. Its losses amounted to at least $6.2 billion. JPMorgan’s settlement with one of the regulators of national banks, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), specifically flagged the safety and soundness issue. The OCC had this to say:

“The credit derivatives trading activity constituted recklessly unsafe and unsound practices, was part of a pattern of misconduct and resulted in more than minimal loss, all within the meaning of 12 U.S.C. § 1818(i)(2)(B).”

But even after the epic financial collapse in 2008 and JPMorgan’s epic gambles with bank depositors’ money a few years later, Congress has left this derivatives ticking time bomb ticking away.

According to a report from the OCC, as of September 30, 2015, insured U.S. commercial banks and savings associations had exposure to $192.2 trillion notional (face amount) of derivatives. The report notes that only four banks hold 90.8 percent of all derivatives: Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs and Bank of America. (See the equally troublesome derivatives holdings of Morgan Stanley here.)

In other words, since the early 90s, instead of reducing systemic risk, Congress has allowed it to dramatically expand. Back then, seven banks represented 90 percent of derivatives activity. Today, just four banks hold 90.8 percent of all derivatives and the dollar amount of those derivatives has exploded.

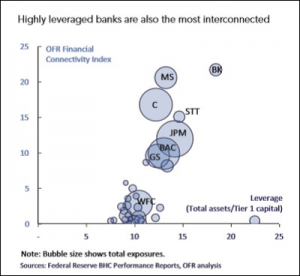

In February of last year, the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Financial Research (OFR) released a new study showing seismic levels of interconnected risk among the largest Wall Street banks.

The OFR report was authored by Meraj Allahrakha, Paul Glasserman, and H. Peyton Young. It found that five U.S. banks had high contagion index values — Citigroup, JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, and Goldman Sachs. (What do those banks all have in common – unfathomable levels of derivatives.)

The OFR authors write:

“…the default of a bank with a higher connectivity index would have a greater impact on the rest of the banking system because its shortfall would spill over onto other financial institutions, creating a cascade that could lead to further defaults. High leverage, measured as the ratio of total assets to Tier 1 capital, tends to be associated with high financial connectivity and many of the largest institutions are high on both dimensions…The larger the bank, the greater the potential spillover if it defaults; the higher its leverage, the more prone it is to default under stress; and the greater its connectivity index, the greater is the share of the default that cascades onto the banking system. The product of these three factors provides an overall measure of the contagion risk that the bank poses for the financial system.”

The words in the OFR report are slightly different than those of the 1994 GAO report but the message is the same: the U.S. financial system is not so much a financial system as it is a giant fireworks factory with a history of lax oversight of its explosive inventory.

That the President who promised hope and change allows this situation to persist, after the greatest Wall Street blowup since 1929, is nothing short of a national scandal.