By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: January 19, 2016

The conventional wisdom was that the Fed’s rate hike on December 16 of last year was going to help big bank stocks by boosting their ability to charge heftier interest rates on loans. That theory has pretty much been relegated to the dust bin of financial fairy tales along with the Fed’s prediction that the slump in oil prices would be “transitory.” Bank stocks have been cratering like it’s early 2008 all over again and oil prices can’t find a floor, having broken through $60, $50, $40 and now $30 a barrel over the past 12 months.

The conventional wisdom was that the Fed’s rate hike on December 16 of last year was going to help big bank stocks by boosting their ability to charge heftier interest rates on loans. That theory has pretty much been relegated to the dust bin of financial fairy tales along with the Fed’s prediction that the slump in oil prices would be “transitory.” Bank stocks have been cratering like it’s early 2008 all over again and oil prices can’t find a floor, having broken through $60, $50, $40 and now $30 a barrel over the past 12 months.

On top of the oil rout, which may spell corporate credit downgrades, bankruptcies, higher loan loss reserves – none of which are good for bank stocks – there are other bank risks not on the public’s radar screen.

Among big U.S. bank stocks, Citigroup has taken the worst drubbing. Even after reporting what were perceived to be fairly good earnings last Friday, its share price fell by 6.41 percent by the close of trading. That brings its stock losses to 30 percent from its July 2015 high. That’s not the sort of behavior one wants to see from one of the country’s largest banks and a stock that lost 60 percent of its market value in one week in 2008 (the week of November 17) and proceeded to receive the largest taxpayer bailout in U.S. history.

The Wall Street Journal expressed this theory on Citigroup’s travails last Friday:

“Doubts about emerging-market growth, for example, sting Citigroup more than its peers given its global exposure. In fact, many investors view its shares as a proxy for expectations about non-U.S. economic growth. A portfolio manager looking to limit exposure to the impact of lower oil or a Chinese slowdown is a natural seller of Citi…The saving grace in all this? The selloff isn’t about worries of banks blowing up. It is more investors throwing in the towel on the idea that things will be getting meaningfully better for them soon.”

The minute U.S. corporate media tells you that “the selloff isn’t about worries of banks blowing up,” you know the worries are about banks blowing up.

There’s three major elements tied to the worry about U.S. mega banks – derivatives, interconnectedness and what investors can’t see until the bank blows up. Even though Morgan Stanley has much smaller foreign exposure than Citigroup according to the Office of Financial Research, its stock has lost 37 percent since its July high, 7 percent more than Citigroup.

Goldman Sachs has lost 29 percent in market value since June; Bank of America is off 22 percent from July and JPMorgan is down by 19 percent in the same period.

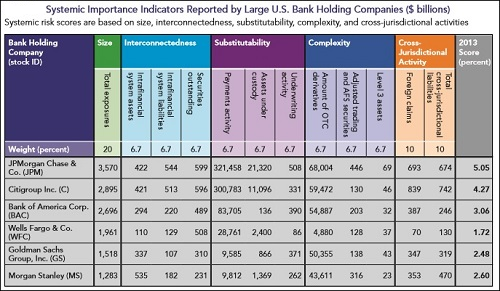

What these five mega Wall Street banks have in common, according to a February 2015 report from the Office of Financial Research (OFR), a unit of the U.S. Treasury Department, is mega intrafinancial system assets and liabilities – in other words, they’re on the hook to each other. The data used by the OFR was as of December 31, 2013. (Wells Fargo, which is a huge bank but not as interconnected, is down just 17 percent since its July 12-month high.)

The OFR report notes the following about the connectivity problem on Wall Street:

“…the default of a bank with a higher connectivity index would have a greater impact on the rest of the banking system because its shortfall would spill over onto other financial institutions, creating a cascade that could lead to further defaults. High leverage, measured as the ratio of total assets to Tier 1 capital, tends to be associated with high financial connectivity and many of the largest institutions are high on both dimensions…The larger the bank, the greater the potential spillover if it defaults; the higher its leverage, the more prone it is to default under stress; and the greater its connectivity index, the greater is the share of the default that cascades onto the banking system. The product of these three factors provides an overall measure of the contagion risk that the bank poses for the financial system.”

Given that the U.S. financial system experienced the largest collapse since the Great Depression just seven years ago; that both the debt of the U.S. government and the Federal Reserve has exploded as a result; and that regulators have repeatedly assured the public that they’ve gotten the risky situation at the big banks under control – we should not be currently witnessing bank stocks melting away like the Wicked Witch of the West. Unless, of course, as Senator Bernie Sanders and the chart below suggest, they actually are the Wicked Witches of the West.