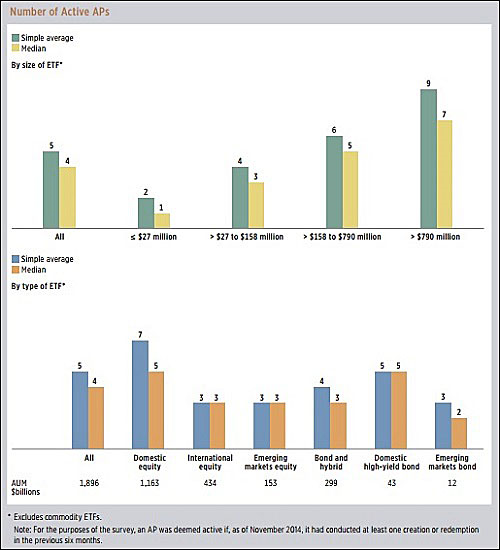

Number of Active Authorized Participants in Exchange Traded Funds (Source: Investment Company Institute)

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: December 15, 2015

The selloff in junk bonds has rattled the markets and is raising questions about just who it is that is providing liquidity to the junk bond Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) — which have magically redeemed billions of dollars in withdrawals from retail investors while the underlying bonds in their portfolio are under severe stress in the broader marketplace. (Both a junk bond mutual fund and a separate hedge fund were forced to freeze investor withdrawals of their cash last week due to illiquidity in the junk bond market.)

Unknown to most retail investors is that there is an entity called an “Authorized Participant” hiding behind the curtain of ETFs that is making that liquidity possible.

According to an August 8, 2014 written question and answer exchange between the National Association of Insurance Commissioners and BlackRock and State Street – two large sponsors of ETFs — the most active Authorized Participants for corporate bond ETFs include “Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley and Cantor Fitzgerald.”

Let’s pause for a moment and think about that. JPMorgan Chase is the largest insured depository bank in the United States. Merrill Lynch was teetering toward failure during the crash of 2008 and was taken over by Bank of America, also one of the top four largest insured depository banks in the U.S. Both Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley became bank holding companies during the 2008 crash and now have access to the Fed’s discount window for emergency borrowing.

It seems pretty obvious why these so called “Authorized Participants” are hiding behind that esoteric title. Their liquidity to ETFs is actually being backstopped by their too-big-to-fail status which is actually backstopped by the U.S. taxpayer.

As Senator Elizabeth Warren told a Senate hearing on March 3 of this year:

“During the financial crisis, Congress bailed out the big banks with hundreds of billions of dollars in taxpayer money; and that’s a lot of money. But the biggest money for the biggest banks was never voted on by Congress. Instead, between 2007 and 2009, the Fed provided over $13 trillion in emergency lending to just a handful of large financial institutions. That’s nearly 20 times the amount authorized in the TARP bailout.

“Now, let’s be clear, those Fed loans were a bailout too. Nearly all the money went to too-big-to-fail institutions. For example, in one emergency lending program, the Fed put out $9 trillion and over two-thirds of the money went to just three institutions: Citigroup, Morgan Stanley and Merrill Lynch.

“Those loans were made available at rock bottom interest rates – in many cases under 1 percent. And the loans could be continuously rolled over so they were effectively available for an average of about two years.”

So what exactly is the role of these Authorized Participants? According to the Investment Company Institute, an industry group whose members are mutual funds, ETFs, closed-end funds and unit investment trusts, it goes like this:

“ETF shares are created when an ‘authorized participant’ deposits a daily ‘creation basket’ (or cash) with the ETF. So let’s get the definitions straight.

“What is an authorized participant? An authorized participant is typically a large institutional investor, such as a broker-dealer, that enters into a contract with an ETF to allow it to create or redeem shares directly with the fund. The authorized participant does not receive compensation from the ETF or the ETF sponsor for creating or redeeming ETF shares.

“What is a creation basket? A creation basket is a specific list of names and quantities of securities or other assets that may be exchanged for shares of the ETF. The creation basket typically either mirrors the ETF’s portfolio or contains a representative sample of the ETF’s portfolio. The contents of the creation basket are made publicly available on a daily basis.

“In return for the creation basket or cash (or both), the ETF issues to the authorized participant a ‘creation unit,’ a large block of ETF shares (generally 25,000 to 200,000 shares). The authorized participant can either keep these ETF shares or sell some or all of them on a stock exchange. ETF shares are listed on a number of stock exchanges, where investors can purchase them as they would shares of a publicly traded company.”

Comparing this process to trading shares of a publicly traded company on a stock exchange is like comparing the Byzantine Empire to Hoboken, New Jersey.

What could possibly go wrong in this trading model? According to the Investment Company Institute, here’s one possibility:

“Citigroup, a major AP [Authorized Participant], temporarily ceased transmitting redemption orders to various ETFs that had foreign underlying securities on June 20, 2013, because it had reached an internal net capital ceiling imposed by its corporate banking parent. According to press reports, Citigroup made the business decision to no longer post collateral in connection with redemption activity in these ETFs. Although fewer APs can quickly step into the international space…one large AP that was active in these ETFs was able to process the redemption requests without any problems. In addition, investors could have turned to the secondary market, which was functioning normally and not showing signs of stress, to sell their ETF shares.”

So what happens when Authorized Participants back away and the secondary market is also under unprecedented stress? Like everything else on Wall Street, there doesn’t seem to be a carefully considered or constructed backup plan.