By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: July 8, 2015

It’s starting to feel like we never actually emerged from the 2008 crisis: the U.S. government and the Federal Reserve simply threw $13 trillion at the crisis and walked away, hoping that an endless zero-interest-rate-policy (Zirp) would patch over the cracks in the global financial system. What we seem to have now is an endless series of rolling crises instead of one big global crisis. The rolling crises, from Puerto Rico to Greece to China’s stock market, all have one thing in common – the unraveling of too much debt. That could rapidly turn into a full-fledged global crisis if policymakers misdiagnose what’s happening, treating the problems as isolated crises instead of a interconnected debt hangover from the go-go years.

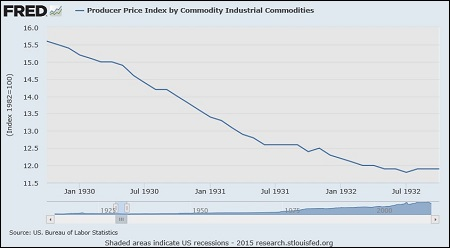

The plunging price action in industrial commodities this week strongly suggests that debt was not sufficiently purged in the 2008-2009 economic meltdown and debt liquidation is back with a vengeance.

The China stock market, the second largest in the world after the U.S., locked down 72 percent of its stocks on Wednesday, according to Bloomberg, with “at least 1,331 companies halted on mainland exchanges and another 747 falling by the 10 percent daily limit.” This has effectively frozen $2.6 trillion of stock from trading, according to Bloomberg.

The Shanghai Composite, which clearly would have fallen by a much greater amount if all stocks had been trading, fell 5.9 percent at the close, bringing its loss to 32 percent from its peak set less than a month ago. The Shenzhen Composite Index, consisting of smaller companies and tech stocks, has plunged 40 percent from its peak this year.

The Chinese government has thrown everything but the kitchen sink at this market and still cannot stem the slide. China has created a clone of the U.S. stock market in 1929: panicky retail investors that are new to the stock market who are heavily margined on borrowed debt and no ability to meet margin calls, forcing them to sell at any price. The Financial Times estimates that 80 to 90 percent of investors in China are retail clients, rather than institutions.

The price action in China spilled over into Japan with the Nikkei dropping 638.95 points or 3.14 percent. After twenty-three minutes of trading this morning, the Dow Jones Industrial Average is down by 182 points.

The price action in China’s stock market is perceived by veteran market watchers as an indicator of a deeper economic malaise in China than the government is willing to admit. This perception is now driving industrial commodity prices deeply into the red. China is a major importer of industrial commodities and its contracting manufacturing base suggests there is more pain ahead in commodities.

Copper is off by 9 percent since Friday with Iron Ore off 11 percent since the beginning of the week and down over 20 percent since June. Bloomberg’s Commodity Index dropped to its lowest closing level since late 2001.

The deflationary trends that had global central banks so worried last year, seem to be back. The idea that the U.S. Federal Reserve would hike rates in the midst of this crisis, pushing up the U.S. dollar and thus accelerating a further decline in commodity prices, is viewed as a highly unlikely outcome.

To put the present situation in sharp focus, Greece has not only closed its banks but its stock market remains shuttered; China has effectively shuttered the bulk of its stock market; industrial commodities, a barometer of the economic health of the world, have resumed their plunge. There is nothing normal about this situation.

As Wall Street On Parade has regularly opined, the core problem is income and wealth inequality, which can only be remedied by restructuring the financial system from that of a predatory wealth transfer mechanism to its proper role as an efficient allocator of capital.

It’s the same problem the U.S. experienced in the 1930s, as explained at the time by President Franklin D. Roosevelt:

“…our basic trouble was not an insufficiency of capital. It was an insufficient distribution of buying power coupled with an over-sufficient speculation in production. While wages rose in many of our industries, they did not as a whole rise proportionately to the reward to capital, and at the same time the purchasing power of other great groups of our population was permitted to shrink. We accumulated such a superabundance of capital that our great bankers were vying with each other, some of them employing questionable methods, in their efforts to lend this capital at home and abroad. I believe that we are at the threshold of a fundamental change in our popular economic thought, that in the future we are going to think less about the producer and more about the consumer. Do what we may have to do to inject life into our ailing economic order, we cannot make it endure for long unless we can bring about a wiser, more equitable distribution of the national income.”