By Pam Martens: December 3, 2014

A JPMorgan Employee Uses a Photo of Oliver Twist to Joke in an Email About How His Group Is Manipulating Electric Markets in California.

On April 29, 2010 at 7:47 in the evening, Francis Dunleavy, the head of Principal Investing within the JPMorgan Commodities Group fired off a terse email to a colleague, Rob Cauthen. The email read: “Please get him in ASAP.”

The man that Dunleavy wanted to be interviewed “ASAP” was John Howard Bartholomew, a young man who had just obtained his law degree from George Washington University two years prior. But it wasn’t his law degree that Bartholomew decided to feature at the very top of the resume he sent to JPMorgan; it was the fact that while working at Southern California Edison in Power Procurement, he had “identified a flaw in the market mechanism Bid Cost Recovery that is causing the CAISO [the California grid operator] to misallocate millions of dollars.” Bartholomew goes on to brag in his resume that he had “showed how units in reliability areas can increase profits by 400%.”

The internal emails at JPMorgan and Bartholomew’s resume are now marked as Exhibit 76 in a two-year investigation conducted by the U.S. Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations into Wall Street’s vast ownership of physical commodities and rigging of commodity markets. Senator Carl Levin, the Chair of the Subcommittee, had this to say about the resume at a hearing conducted on November 21:

“There’s two things that I find incredible about this. First, that anyone would advertise in a resume that they know about a flaw in the system — signaling that they’re ready and willing to exploit that flaw. And, second, that somebody would hire the person sending that signal.”

JPMorgan not only hired Bartholomew, according to the Senate’s findings, but within three months from the date of the email to Dunleavy, “Bartholomew began to develop manipulative bidding strategies focused on CAISO’s make-whole mechanism, called Bid Cost Recovery or BCR payments.” By early September, the strategy to game the system was put into play. By October, the JPMorgan unit was estimating that the strategy “could produce profits of between $1.5 and $2 billion through 2018.”

The strategy of gaming the Bid Cost Recovery payments, or BCR, was producing such windfall profits that another JPMorgan employee sent an email on October 22, 2010 to his colleagues, joking about the success by featuring a photograph of Oliver Twist holding out an empty bowl with the subject line: “Please sir! mor BCR!!!!”

During the Senate hearing, Senator Levin commented on the email and the reference to Oliver Twist, stating:

“Now the BCR refers to the make-whole payments that JPMorgan was using to unfairly profit from the system. And I gotta tell you it’s mighty offensive to me that JPMorgan portrays its actions as a joke, comparing itself to a poor orphan needing charity when it was ripping off consumers.”

The legal entity that carried out the strategy on behalf of the Commodities Group was JPMorgan Ventures Energy Corporation or JPMVEC. The voluminous report that was released simultaneously with the Senate hearings, explains the method JPMorgan used to rig the market as follows:

“As part of the strategy, in the Day Ahead market, JPMVEC submitted the lowest bid allowed under CAISO rate schedules. The bid was generally at the rate of -$30 per megawatt hour, which meant that JPMVEC was offering a negative bid and was willing to pay the buyer to take the electricity, despite the costs involved in producing it. Its bids were reviewed by electronic software, which did not grasp the intent behind JPMVEC’s below-cost bids. JPMVEC’s -$30 bids were well below where the Day Ahead Market actually settled, which was typically in the positive range of $30 – $35 per megawatt hour, so the bids routinely secured Day Ahead awards from CAISO. JPMVEC was then given a Day Ahead award at the prevailing market price regardless of its initial low bid price. In addition, its traders knew that if JPMVEC won a Day Ahead award, JPMVEC could also qualify for a BCR payment on its minimum load equal to twice its costs, resulting in a total payment well in excess of market prices.

“In essence, JP Morgan sold high priced electricity to CAISO, received a BCR payment equal to twice its costs, and also received a payment at the prevailing marketplace price for the electricity provided – in effect, it was paid three times for the same electricity.”

After CAISO and MISO, the Midwest grid operator, began to file complaints with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), an investigation commenced and was eventually settled on July 30, 2013 with JPMorgan agreeing to pay a total of $410 million in penalties and disgorgements, a small pittance for a Wall Street bank that had $18 billion in profits in 2013.

The FERC settlement document notes that: “During the relevant period, Dunleavy was one of eight direct reports to Blythe Masters, the head of JP Morgan’s Global Commodities Group. Starting in 2010, Dunleavy supervised Andrew Kittell and John Bartholomew, including with respect to bids developed by Principal Investments into CAISO and MISO.” To this day, none of the JPMorgan employees who engaged in the strategy have been charged by regulators or prosecutors. Dunleavy retired in 2013; Masters no longer works for JPMorgan. The status of Kittell and Bartholomew is unknown.

Senator Levin also brought out during the hearing that while JPMorgan was being investigated, it continued to engage in other manipulative electricity schemes, a total of 11 in all. The Senate report noted that FERC officials told the Subcommittee “that in the years since Congress gave FERC enhanced anti-manipulation authority in the Energy Policy Act of 2005, the CAISO and MISO regulators had never before witnessed the degree of blatant rule manipulation and gaming strategies that JPMorgan used to win electricity awards and elicit make-whole payments.”

The two-year Senate investigation was multi-faceted. It looked at the heretofore vast secret holdings of physical industrial commodities, power plants, pipelines, oil storage terminals and aluminum warehouses owned variously by JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley; at how related commodity markets have been rigged or could potentially be rigged by owning these assets while making massive trades in financial instruments related to them; and why the Federal Reserve, charged with ensuring the safety and soundness of banks, had not seen the potential for catastrophic bank losses from pipeline ruptures or tanker oil spills or power plant explosions.

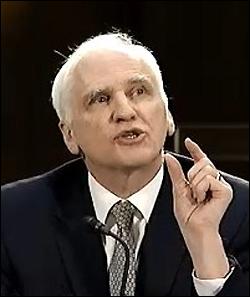

Daniel Tarullo, Member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Testifying at a November 21, 2014 Senate Hearing

Daniel Tarullo, a member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, testified at the second day of Senate hearings. Tarullo said the Federal Reserve has put the issue out for public comment. His written testimony said that the request for public comment has thus far elicited 16,900 form letters and 184 unique responses. Tarullo further indicated that the issue of the potential for catastrophic losses is being carefully looked at by the Federal Reserve.

According to the Senate report, at one point in 2010, JPMorgan “owned or had rights to the energy output of 31 power plants across the country.” The Senate report also found that when JPMorgan acquired its power plants, it did not have authority to own or operate them. The Federal Reserve eventually authorized JPMorgan “to enter into tolling agreements, energy management contracts, and long-term supply contracts with power plants,” but it did not authorize JPMorgan to outright own power plants. In response, JPMorgan asserted that it could retain direct ownership of three power plants under its merchant banking authority.

The Senate report quotes from a Federal Reserve examination document that criticizes JPMorgan’s position. It states: “JPM has pressed on the boundaries of permissible activities including integrating merchant banking investments into trading activities and pursuing activity that may appear ‘commercial in nature,’ as well as pushed regulatory limits and their interpretation.”

The Subcommittee also noted regarding the three power plants that JPMorgan continues to own that “U.S. federal law attaches liability for catastrophic environmental events to both owners and operators. By choosing to become the direct owner of the three power plants, instead of holding tolling agreements with them as permitted under its complementary authority, JPMorgan has increased the financial holding company’s liability for damages, should disaster strike. Even well–run power plants carry catastrophic event risks. If the worst case scenario should occur, JPMorgan should be prepared to cover the potential losses, without U.S. taxpayer assistance.”