By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: May 31, 2023 ~

Last Friday, at the start of Memorial Day weekend, researchers at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) released an analysis of where they think the U.S. economy is headed and the headwinds (read gale force winds) that can, potentially, be expected along the way.

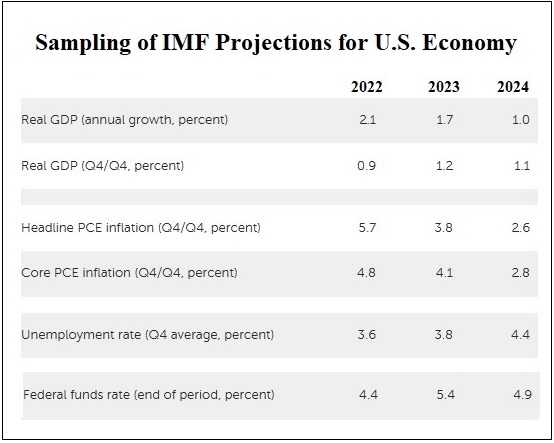

Folks on Wall Street who were hoping that the Fed was at the end of its rate-hiking cycle, with a more dovish Fed juicing stock market returns later this year, likely had their holiday weekend ruined with this projection from the IMF:

“Achieving a sustained disinflation will necessitate a loosening of labor market conditions that, so far, has not been evident in the data. To bring inflation firmly back to target will require an extended period of tight monetary policy, with the federal funds rate remaining at 5¼–5½ percent until late in 2024.”

The Fed’s inflation target is 2 percent. As of its last report on May 10, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the Consumer Price Index rose 0.4 percent in April on a seasonally-adjusted basis while the all-items index increased 4.9 percent over the last 12 months before seasonal adjustment.

The Fed’s inflation target of 2 percent remains elusive despite the fact that the Fed began its rate hikes more than a year ago on March 17, 2022 and has hiked rates 10 times – the fastest pace in 40 years. The Fed Funds rate has moved from 0-0.25 percent on March 16, 2022 to the current 5.0-5.25 percent, the highest level for Fed Funds in more than 15 years.

While the Fed has not cracked the tight labor market or inflation conundrums with its rapid rate increases, it has produced serious cracks in the banking system. Between March 10 and May 1 of this year, the second, third and fourth largest bank failures in U.S. history occurred: First Republic Bank, Silicon Valley Bank, and Signature Bank, respectively. (Washington Mutual was the largest bank failure in 2008.)

Thus, it is no surprise that the condition of the balance sheets of banks in the U.S. received a significant amount of attention in the recent IMF report – as did the timidity of federal regulators to do anything more than destroy a forest of trees interminably writing warnings to troubled banks while taking no concrete action. The IMF researchers write:

“First, a higher path for interest rates could reveal larger, more systemic balance sheet problems in banks, nonbanks, or corporates than we have seen to-date. Unrealized losses from holdings of long duration securities would increase in both banks and nonbanks and the cost of new financing for both households and corporates could become unmanageable.”

Let’s pause here for a moment and explain in layman’s terms why higher interest rates result in losses in the market prices of existing bonds, i.e. “long duration securities” as referenced above. This is typically explained to the public in the following cryptic phrase: “Bond prices have an inverse relationship to interest rates.”

This is the translation of that cryptic phrase:

Let’s say that a bank is holding as an investment security the U.S. Treasury bond maturing on May 15, 2041 that was issued with a fixed rate of 2.25 percent through the life of the bond. The current trading price of that bond has to decline so that its yield is comparable to what other Treasury bonds of that maturity are yielding. So that precise Treasury bond is trading in the market right now at around $762.60 per $1,000 face amount at maturity, in order to bring its yield in line with the approximate 4 percent that other like Treasury bonds are yielding. If that bond was purchased at par (at $1,000 face amount), the bank that is the owner of that bond is sitting on a paper loss of about 24 percent of the principal it invested.

If a bank is holding tens of billions of dollars of bonds that were issued with low fixed rates, it’s sitting on vast amounts of losses – which may be getting murky accounting treatment. (See JPMorgan Chase Transferred $347 Billion in Debt Securities Over the Last 3 Years to Inflate Its Capital Using a Controversial Maneuver.)

At the March 6 meeting of the Institute of International Bankers, FDIC Chairman Martin Gruenberg had this to say regarding these bond losses at banks:

“The current interest rate environment has had dramatic effects on the profitability and risk profile of banks’ funding and investment strategies. First, as a result of the higher interest rates, longer term maturity assets acquired by banks when interest rates were lower are now worth less than their face values. The result is that most banks have some amount of unrealized losses on securities. The total of these unrealized losses, including securities that are available for sale or held to maturity, was about $620 billion at yearend 2022. Unrealized losses on securities have meaningfully reduced the reported equity capital of the banking industry.”

The IMF highlighted the following in its report on Friday:

“Recent bank failures highlight the potential systemic risks posed by even relatively small financial intermediaries. The past few months have focused attention on poor risk management by individual institutions, vulnerabilities created by the regulatory ‘tailoring’ that was put in place in 2018, and inadequate supervisory oversight. Important questions have been raised about the insufficiently assertive stance taken by bank supervisors as well as the effectiveness of the stress tests that were undertaken to identify the extent of bank vulnerabilities and the potential for systemic contagion. It has become clear that, despite correctly diagnosing the vulnerabilities in the system, the actions that were subsequently taken by supervisors neither prevented the most vulnerable banks from continuing to grow rapidly nor precipitated fundamental changes to these banks’ operations.”

As for how long banking regulators have known that the stress tests were a dangerous illusion, see our report: Three Federal Studies Show Fed’s Stress Tests of Big Banks Are Just a Placebo.

The April 28 report on bank failures from Michael Barr, the Vice Chairman for Supervision at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, highlighted issues that he wants to see addressed regarding banks’ balance sheets:

“…we are also going to evaluate how we supervise and regulate liquidity risk, starting with the risks of uninsured deposits. Liquidity requirements and models used by both banks and supervisors should better capture the liquidity risk of a firm’s uninsured deposit base. For instance, we should re-evaluate the stability of uninsured deposits and the treatment of held to maturity securities in our standardized liquidity rules and in a firm’s internal liquidity stress tests. We should also consider applying standardized liquidity requirements to a broader set of firms. Any adjustments to our liquidity rules would, of course, go through normal notice and comment rulemaking and have appropriate transition rules, and thus would not be effective for several years.

“With respect to capital, we are going to evaluate how to improve our capital requirements in light of lessons learned from SVB [Silicon Valley Bank]. For instance, we should require a broader set of firms to take into account unrealized gains or losses on available-for-sale securities, so that a firm’s capital requirements are better aligned with its financial positions and risk. Again, these changes would not be effective for several years because of the standard notice and comment rulemaking process and would be accompanied by an appropriate phase-in.”

Given that the U.S. has just experienced the worst banking crisis since the Wall Street implosions of 2008; given that Silicon Valley Bank’s customers had queued up to yank 85 percent of its deposits in a 48-hour period on March 9 and 10 — that famous line from the movie, “Top Gun,” comes to mind regarding Barr’s notion that the U.S. has two years to fiddle around with regulatory reform: “Bull sh*t…get on it.”