By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: April 26, 2021 ~

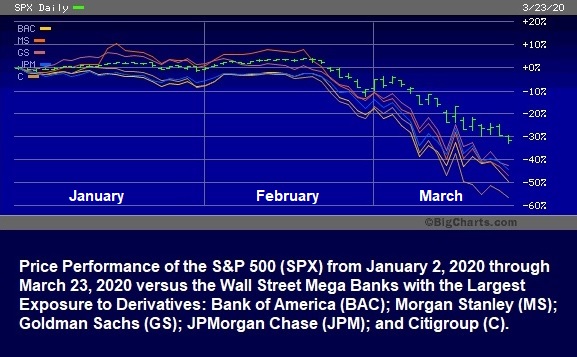

On Wednesday, March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 to be a pandemic. From that point on, through March 23, the share price performance of the Standard & Poor’s 500 began to diverge dramatically from the share price performance of the mega banks on Wall Street. (See chart above.)

From the start of the year in 2020, the S&P 500 fell a little more than 30 percent through March 23 while Bank of America, Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, and JPMorgan Chase were down from 40 to 50 percent. Citigroup was down by a stunning 56 percent. (Citigroup had closed at $79.89 on December 31, 2019. By the close of trading on March 23, 2020, it was a $35.39 stock.)

We compared these bank stocks to the S&P 500 because the companies that make up the S&P 500 index are the corporate customers that these banks are supposed to be lending to. Why are the banks’ corporate customers performing better in a crisis than the banks? Why are the mega banks draining confidence from the financial system with tanking stock prices? Why is Citigroup, a basket case in the last financial crisis, performing like a new basket case in this crisis?

What happened as a result of the tanking share prices of the mega bank stocks in the spring of 2020 is that the Federal Reserve had to quickly reassemble many of the same Wall Street bailout programs that it had created in 2008, for example: the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF), the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF), the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF), the Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF), and numerous other programs and bailout measures.

The concept of taxpayers backstopping federally-insured banks holding the life savings of average Americans is that in times of economic crisis those banks will not have to worry about bank runs and will be able to lend to consumers and businesses in order to get the economy back on a sound course.

But as Americans witnessed in horror in 2008, it was the mega banks themselves that actually brought on the greatest economic crisis since the Great Depression through greed, reckless derivative bets and insane packaging and selling of subprime debt that bank insiders knew was doomed to fail.

The Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation passed in 2010 was supposed to fix the ugly warts that were exposed in the aftermath of the 2008 financial collapse on Wall Street. But it fixed nothing. All it did was kick the can down the road to the next crisis.

What caused the Wall Street bank stocks to tank so much worse than the broader market in March 2020 is the same thing that caused the banks to tank much worse than the broader market in 2008 – interconnectivity via derivatives and leverage.

The federal agency created under the Dodd Frank legislation, the Office of Financial Research (OFR), strongly warned about these five banks and their interconnectivity in a report in 2015.

According to the OFR study:

“The larger the bank, the greater the potential spillover if it defaults; the higher its leverage, the more prone it is to default under stress; and the greater its connectivity index, the greater is the share of the default that cascades onto the banking system. The product of these three factors provides an overall measure of the contagion risk that the bank poses for the financial system. Five of the U.S. banks had particularly high contagion index values — Citigroup, JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, and Goldman Sachs.”

These five banks are highly interconnected via derivatives because they have exposure to the same counterparties (the entities on the other side of their trillions of dollars in derivative trades). Sophisticated traders on Wall Street understand these risks and want to run from these banks in any crisis situation.

According to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency’s most recent report for the quarter ending December 31, 2020, these same five holding companies held the notional (face amount) of $185.61 trillion in derivative contracts – representing a mind-numbing 85 percent of all derivatives in the banking system, which consists of more than 5,000 banks. (See Table 2 in the Appendix here.)

Despite the fact that everyone on Wall Street that was paying attention in March of 2020 could see that these banks’ tanking share prices posed systemic risk to the U.S. financial system, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell testified multiple times before Congress in 2020 that these banks were “a source of strength.” Powell delivered the same message at his press conferences.

The Fed’s stress tests are another such form of propaganda. The OFR released a report in 2016 which found a critical flaw in the methodology of the Fed stress tests. The OFR researchers who conducted the study, Jill Cetina, Mark Paddrik, and Sriram Rajan, found that the Fed’s stress tests are measuring counterparty risk for the trillions of dollars in derivatives held by the largest banks on a bank by bank basis. The real problem, according to the researchers, is the contagion that could spread rapidly if one big bank’s counterparty was also a key counterparty to other systemically important Wall Street banks. The researchers write:

“A BHC [bank holding company] may be able to manage the failure of its largest counterparty when other BHCs do not concurrently realize losses from the same counterparty’s failure. However, when a shared counterparty fails, banks may experience additional stress. The financial system is much more concentrated to (and firms’ risk management is less prepared for) the failure of the system’s largest counterparty. Thus, the impact of a material counterparty’s failure could affect the core banking system in a manner that CCAR [one of the Fed’s stress tests] may not fully capture.”

Interconnectedness and concentration risk were also called out in the report on the 2008 financial collapse by the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. The final report found:

“Large derivatives positions, and the resulting counterparty credit and operational risks, were concentrated in a very few firms. Among U.S. bank holding companies, the following institutions held enormous OTC derivatives positions as of June 30, 2008: $94.5 trillion in notional amount for JP Morgan, $37.7 trillion for Bank of America, $35.8 trillion for Citigroup, $4.1trillion for Wachovia, and $3.9 trillion for HSBC. Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, which began to report their holdings only after they became bank holding companies in 2008, held $45.9 and $37 trillion, respectively, in notional amount of OTC derivatives in the first quarter of 2009. In 2008, the current and potential exposure to derivatives at the top five U.S. bank holding companies was on average three times greater than the capital they had on hand to meet regulatory requirements. The risk was even higher at the investment banks. Goldman Sachs, just after it changed its charter, had derivatives exposure more than 10 times capital. These concentrations of positions in the hands of the largest bank holding companies and investment banks posed risks for the financial system because of their interconnections with other financial institutions.”

On top of the taxpayer bailouts in 2008, the Fed itself secretly funneled $29 trillion in cumulative loans to Wall Street banks, their foreign derivative counterparties and foreign central banks, then waged a multi-year court battle in an attempt to keep that information from the public. (It lost its court battle.)

Isn’t it long past the time for Congress to get serious about removing the Fed, a thoroughly captured regulator, from any involvement with supervising the Wall Street banks that it plays sugar daddy to on a regular basis?

See Wall Street On Parade’s archive of articles on how the Fed’s 2019-2021 Wall Street bailout is playing out.