![Closing Price of the S&P Index on Friday, March 27, 2020, Versus Bank of America [BAC], Citigroup[C], Deutsche Bank [DB], Goldman Sachs [GS], JPMorgan Chase [JPM], Morgan Stanley [MS], AIG, and Ameriprise Financial [AMP].](https://wallstreetonparade.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Closing-Stock-Prices-of-SP-500-Versus-JPMorgan-Chase-and-AIG-on-Friday-March-27-2020.png)

Closing Price of the S&P 500 Index on Friday, March 27, 2020, Versus Bank of America [BAC], Citigroup[C], Deutsche Bank [DB], Goldman Sachs [GS], JPMorgan Chase [JPM], Morgan Stanley [MS], AIG, and Ameriprise Financial [AMP]. (Source: BigCharts.com)

Warren Buffett is credited with the quote: “Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.”

Friday’s closing prices among some of the heavily interconnected mega Wall Street banks and insurance companies known to be counterparties to Wall Street’s derivatives appeared to show who’s swimming naked in the realm of derivatives – naked meaning who has sold derivative protection (gone short the risk) on something that is blowing up.

As the chart above shows, the S&P 500 stock index (SPX) closed with a loss of 3.37 percent while the following three stocks closed with more than double that percentage of loss: Deutsche Bank was down by 7.44 percent; JPMorgan shed 7.12 percent while AIG was off by 7.27 percent.

When the Federal Reserve needs to create a hodgepodge of secretive Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) and run bailouts of $4 trillion; and the Fed gets language in the newly passed stimulus bill that it can hold its meetings in secret with no minutes provided to the public; and the President of the United States signs the stimulus bill with a signing statement announcing only he will determine what Congress gets to know about where the bailout funds go, you know that something is happening under the surface on Wall Street that is just too repugnant to be reported to the American people.

And when you see three firms like JPMorgan Chase, Deutsche Bank and AIG trading as outliers to their peers, only a fool wouldn’t see them as a potential connection to this need for super secrecy.

Here are some key points to remember at this point in time.

JPMorgan Chase’s Chairman and CEO, Jamie Dimon, has serially bragged for years in his annual letter to shareholders about how the bank has a “fortress balance sheet.” But when your stock is losing twice the amount of the S&P 500 and eclipsing the losses of its peer banks on a Friday, there’s something seriously wrong with that balance sheet.

And, unfortunately, this would not be the first time that JPMorgan Chase got on the wrong side of a derivatives trade. In 2012, Jamie Dimon allowed a woman with no trading licenses, Ina Drew, to supervise traders in London who gambled with hundreds of billions in depositors’ money and lost at least $6.2 billion making bets on exotic derivatives. It became known as the London Whale scandal because the trades were so big that they rocked the market and a hedge fund tipped off the media. The trades were made using deposits from within the federally-insured bank at JPMorgan Chase and resulted in an FBI and Senate investigation along with $1 billion in fines and settlements. The U.S. Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations wrote this about the matter:

“The JPMorgan Chase whale trades provide a startling and instructive case history of how synthetic credit derivatives have become a multi-billion dollar source of risk within the U.S. banking system. They also demonstrate how inadequate derivative valuation practices enabled traders to hide substantial losses for months at a time; lax hedging practices obscured whether derivatives were being used to offset risk or take risk; risk limit breaches were routinely disregarded; risk evaluation models were manipulated to downplay risk; inadequate regulatory oversight was too easily dodged or stonewalled; and derivative trading and financial results were misrepresented to investors, regulators, policymakers, and the taxpaying public who, when banks lose big, may be required to finance multi-billion-dollar bailouts.”

On September 17, 2019, months before there were any reports of a coronavirus outbreak anywhere in the world, the Federal Reserve had to intervene in the repo loan market on Wall Street because big banks were backing away from making loans to some financial institutions. From that day forward to the present, the Fed would shell out hundreds of billions of dollars in repo loans each week to the trading houses on Wall Street, whom it calls its primary dealers.

And in the first six months of last year, also long before coronavirus appeared on the scene, Reuters reported that JPMorgan Chase had inexplicably reduced the reserves it was holding at the Fed by $158 billion, or a stunning 57 percent. Exactly what did it need that money for and why did the Fed let it draw down those reserves?

On September 24 and 25 of last year, Deutsche Bank’s headquarters in Frankfurt, Germany was being raided by police for the second time in less than a year. The police were probing a vast money laundering operation in Europe. Another money laundering probe at Deutsche Bank is not good news. On January 30, 2017, Deutsche Bank was fined a total of $630 million by U.S. and U.K. regulators over claims it had laundered upwards of $10 billion on behalf of Russian investors.

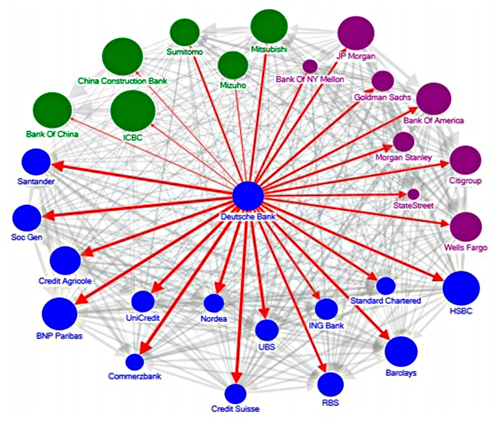

In June 2016, The International Monetary Fund (IMF) released a report that found that Deutsche Bank posed the greatest threat to global financial stability than any other bank because of its interconnections to Wall Street mega banks and large banks in Europe. (See graph below.) JPMorgan Chase was one of the banks with the largest amount of exposure to Deutsche Bank.

On July 7, 2019 Deutsche Bank confirmed plans to fire 18,000 workers and reorganize into a good bank/bad bank. The bad bank will hold assets it plans to sell. Currently, Deutsche Bank’s share price is hovering near historic lows.

We know that AIG is back in the game of derivatives again after being seized by the U.S. government over its derivative losses in September of 2008. As insane as it sounds that federal regulators would allow this to happen, the Office of Financial Research, a unit of the U.S. Treasury, reported in its 2017 Financial Stability Report that the mega banks on Wall Street were once again interconnected through derivatives to insurance companies that included AIG, Lincoln National Corp., Ameriprise Financial, Prudential Financial, and Voya Financial.

This is a chart that AIG was eventually forced to release showing that more than half of its bailout money came in its front door and went out the backdoor to pay off Wall Street and foreign trading houses. The chart shows that Goldman Sachs received $12.9 billion of the funds; Societe Generale received $11.9 billion; Merrill Lynch and its U.S. banking parent, Bank of America, received a combined $11.5 billion; the British bank, Barclays, received $8.5 billion; while Citigroup, which was secretly drinking at the Fed’s trough to the tune of $2.5 trillion in cumulative loans to cover its own losses, got $2.3 billion from AIG.

Systemic Risk Among Deutsche Bank and Global Systemically Important Banks (Source: IMF — “The blue, purple and green nodes denote European, US and Asian banks, respectively. The thickness of the arrows capture total linkages (both inward and outward), and the arrow captures the direction of net spillover. The size of the nodes reflects asset size.”)