By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: October 22, 2024 ~

Four researchers at the University of Westminster School of Finance and Accounting in London have taken a hard look at the much-touted Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation in the U.S. that was signed into law by President Barack Obama in 2010. The voluminous 848-page bill followed the greatest financial crash in the U.S. since the Great Depression. Unfortunately, it was big on word count and short on iron-clad reforms, leaving the implementation of final rules to be negotiated by revolving-door regulators and an army of Wall Street lobbyists and lawyers. (For how that has played out over the ensuing 14 years, see here, here, here and here.)

The authors of the study are Dr. Julie Ayton; Professor Abdelhafid Benamraoui; Dr. Huyen (Trang) Ngo; and Dr. Stefan van Dellen. They define the purpose of the study as follows:

“The research paper tests two critical research hypotheses, (i) whether the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act reduced bank post-merger contribution to systemic risk, and (ii) its role in solving the too-big-to-fail problem induced by large bank mergers. The study results reject both hypotheses indicating that the Dodd-Frank Act was ineffective at reducing systemic risk and in particular the risk attributed to mergers among larger banks, bringing back the fundamental issue and argument of too-big-to-fail and how this can be addressed through regulatory changes or reinforcement.”

A key finding of their study is the following:

“We also find that the larger the bidder, the greater its contribution to systemic risk, but only in the post-Dodd-Frank period. In other words, the post-legislation increase in systemic risk contribution is even more important for large acquiring banks.”

That finding on bigness is in line with an international banking study using 150 years of data that we reported on in October 2023. We wrote at the time:

“It took eight years of research to compile a data set of annual balance sheets of more than 11,000 commercial banks dating back to 1870 in 17 advanced economies. And in every country, the study arrived at the same finding: concentrating the banking system in the hands of five or less giant banks leads to financial instability and more severe financial crises. The bank balance sheets of the following countries were examined: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.”

In the United States, there are just four commercial megabanks with more than $1 trillion in assets. As of June 30, those four are: JPMorgan Chase Bank NA with $3.5 trillion in consolidated assets; Bank of America NA with $2.6 trillion; Wells Fargo Bank NA with $1.7 trillion; and Citigroup’s Citibank NA with $1.678 trillion in consolidated assets.

JPMorgan Chase Bank NA is not just the largest bank in the United States by a large margin but it has been officially declared the riskiest bank by a large margin by its regulators.

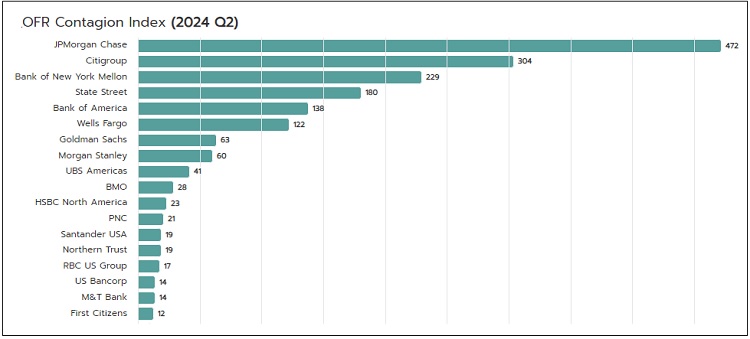

The federal agency that is charged with providing an early warning system for serious cracks in financial stability is the Office of Financial Research (OFR). At the end of the first quarter of 2023, its Contagion Index gave JPMorgan Chase Bank a grade of 420, which ranked it dramatically more dangerous than its peer banks.

But in the following quarter of 2023, its federal banking regulators approved JPMorgan Chase Bank purchasing the failing bank, First Republic Bank. According to the OFR, JPMorgan Chase Bank’s Contagion Index reading now stands at 472, dwarfing its peer banks by an ever-widening margin. (See chart above.)

Michael Hsu is the Acting Comptroller of the Currency, the regulator of national banks (those operating across state lines). He was the one federal banking regulator that could have rejected JPMorgan Chase’s offer to buy First Republic Bank.

At a July 12, 2023 Senate hearing, Senator Elizabeth Warren had this to say about Hsu’s conduct:

“When First Republic Bank collapsed in April, the bank was ultimately sold to the biggest bank in America, JP Morgan Chase. That sweetheart deal cost the Federal Deposit Insurance Fund $13 billion. Meanwhile, overnight, the country’s biggest bank got $200 billion bigger. And what happened to the regulators? The Acting Comptroller of the Currency, Michael Hsu, rubber stamped the deal in record time. When I asked Mr. Hsu at a hearing in May to explain how this merger was approved, he was unable to provide a clear answer.

“But the overall picture gets worse. Instead of inattentive regulators who don’t use their tools to block increasing consolidation, leaders within the Biden Administration seem to be inviting more mergers. In a May 2023 statement before the House Financial Services Committee, Acting Comptroller Hsu reassured banks that the agency would be ‘open-minded’ while considering merger proposals….”

Senator Warren said this attitude was “courting disaster.”

JPMorgan Chase’s history of gobbling up its commercial bank competitors shows just how meaningless anti-trust law has become in the United States. In 1955, Chase National Bank merged with The Bank of the Manhattan Company to form Chase Manhattan Bank. In 1991, Chemical Bank and Manufacturers Hanover announced their merger. Both banks had been severely weakened – Chemical from bad real estate loans and Manufacturers from bad loans to developing nations. In 1995, Chemical Bank merged with Chase Manhattan Bank. In 2000, JPMorgan merged with Chase Manhattan Corporation. In 2004, JPMorgan Chase merged with Bank One. In 2008, during the height of the financial crisis, JPMorgan Chase was allowed to buy Washington Mutual. These are just the largest bank consolidations. Over the years, Chase acquired dozens of smaller banks.

At the time of JPMorgan Chase’s purchase of Washington Mutual in 2008 – WaMu was the largest bank failure in U.S. history. In 2023, when JPMorgan Chase was allowed to purchase First Republic Bank, it was the second largest bank failure in U.S. history.

JPMorgan Chase was also allowed to buy the failing Bear Stearns during the banking crisis of 2008, but Bear Stearns did not own a federally-insured commercial bank in the U.S. However, Bear Stearns did own Bear Stearns Bank Ireland, which JPMorgan renamed as JPMorgan Bank (Dublin) PLC. In 2012, JPMorgan Chase wrote that it was “the only EU passported bank in the non-bank chain of JPMorgan and provides the firm with direct access to the European Central Bank repo window.”

Increasingly, federal banking regulators function as little more than deer caught in the headlights.