By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: April 11, 2024 ~

The Fed’s unprecedented experiments with years of ZIRP (Zero Interest Rate Policy) and QE (Quantitative Easing), where it bought up trillions of dollars of low-yielding U.S. Treasuries and agency Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) and quietly parked them on its balance sheet, are now posing a threat to the Fed’s flexibility in conducting monetary policy. (Since 2008, the Fed’s concept of conducting monetary policy has come to enshrine serial Wall Street mega bank bailouts as a regular part of its monetary policy. Large and growing cash losses at the Fed may seriously crimp such future bailouts.)

The Fed’s unprecedented experiments with years of ZIRP (Zero Interest Rate Policy) and QE (Quantitative Easing), where it bought up trillions of dollars of low-yielding U.S. Treasuries and agency Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) and quietly parked them on its balance sheet, are now posing a threat to the Fed’s flexibility in conducting monetary policy. (Since 2008, the Fed’s concept of conducting monetary policy has come to enshrine serial Wall Street mega bank bailouts as a regular part of its monetary policy. Large and growing cash losses at the Fed may seriously crimp such future bailouts.)

As of last Wednesday, according to Fed data, the Fed was sitting on $6.97 trillion of debt instruments it had predominantly purchased at very low fixed rates of interest. Because the interest rate (coupon) is fixed for these past purchases, when new bonds are issued in the marketplace at higher interest rates, they become more attractive and the current market value of the low-yielding fixed-rate bonds fall. U.S. Treasuries and agency MBS guarantee principal at maturity but if the securities have to be sold prior to maturity they will be sold at their current market value. This is what triggered the death spiral at Silicon Valley Bank in March of last year.

Silicon Valley Bank announced that it had sold a $21 billion bond portfolio (that was yielding less than 2 percent when current interest rates on notes and bonds were twice that amount). It reported a $1.8 billion after-tax loss on the bond sale. Losses negatively impact capital. The hit to capital panicked the very large amount of uninsured depositors at the bank (those holding more than the $250,000 the FDIC insures per depositor, per bank) and triggered an unprecedented bank run in terms of speed and scope. According to a report from the Fed, Silicon Valley Bank had deposit outflows of $40 billion on March 9, and another $100 billion of deposits queued up to leave on March 10 – which together would have been 85 percent of the bank’s deposit base. The FDIC had to step in as receiver and take over the failed bank.

Compared to the Fed, Silicon Valley Bank was a minnow. At the time of its failure in March 2023, Silicon Valley Bank had $212 billion in assets. As of last Wednesday, the Fed had $7.4 trillion in assets. Just one of the Fed’s 12 regional Fed banks, the New York Fed, is 18 times the size of Silicon Valley Bank.

According to the Fed’s latest asset breakdown, as of April 3 the New York Fed, which is by far the largest of the Fed’s regional banks, has $3.88 trillion in assets and $2.77 trillion in deposits.

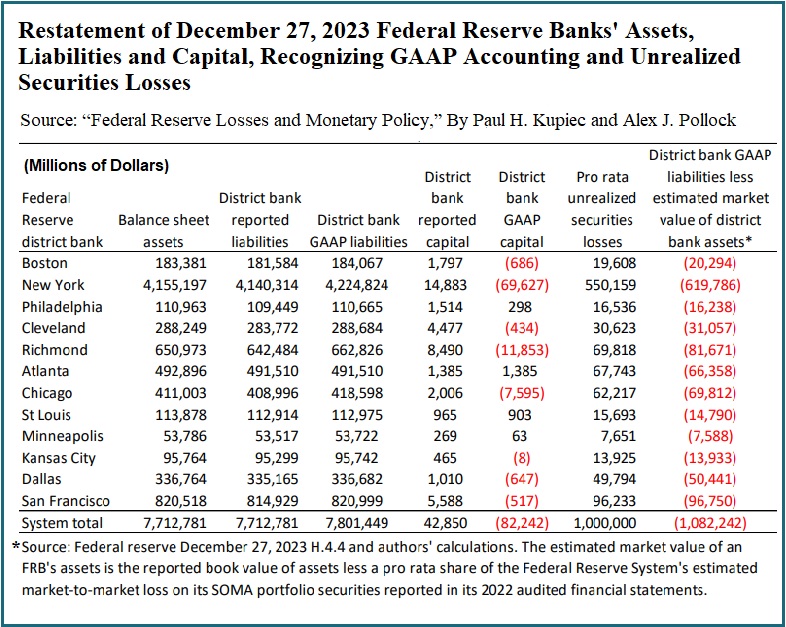

Unfortunately, using GAAP accounting, both the Fed itself and the New York Fed have negative capital. And if interest rates continue to rise in response to inflationary pressures, that situation could get much worse. As the chart below indicates, as of December 27, 2023, using GAAP accounting, the Fed had negative capital of $82 billion while the New York Fed represented $69.6 billion of that negative capital, or 85 percent. That’s before taking into account the approximate $1 trillion in unrealized losses on the Fed’s portfolio of underwater debt securities. The final column on the chart below reflects that calculation. (The Fed does not mark its securities to market, on the basis that it plans to hold them to maturity.)

In January, two researchers, Paul Kupiec and Alex Pollock, put the capital problem and operating losses at the Fed into sharp focus with a report published at the think tank, American Enterprise Institute (AEI).

Kupiec is an exceptionally well-credentialled senior fellow at AEI. Prior to joining the think tank, Kupiec was an Associate Director of the Division of Insurance and Research within the Center for Financial Research at the FDIC, where he oversaw research on bank risk measurement and the development of regulatory policies such as Basel III. Kupiec was also Director of the Center for Financial Research at the FDIC and Chairman of the Research Task Force of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Other prior posts included work at the IMF, Freddie Mac, JPMorgan and at the Division of Research and Statistics at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Kupiec holds a Doctorate in economics — with a specialization in finance, theory, and econometrics — from the University of Pennsylvania.

Pollock is a Senior Fellow at the Mises Institute and also well-credentialled. He previously served as Principal Deputy Director of the Office of Financial Research (OFR), the federal agency created under the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010 to keep federal regulators on top of potential risks to financial stability. Pollack was also the former President and CEO of the Federal Home Loan Bank of Chicago from 1991 to 2004. Pollock is a graduate of Williams College, the University of Chicago, and Princeton University. His latest book, which he co-authored with Howard B. Adler, is Surprised Again! — The Covid Crisis and the New Market Bubble (2022).

The researchers write:

“Notwithstanding the claims made by current and former Federal Reserve officials, the Fed’s cash operating losses and unrealized interest rate losses have already changed the way the Fed conducts monetary policy. In the past, when the Fed wanted to raise rates or shrink member bank reserve balances, it would sell SOMA [System Open Market Account] securities. But today, with the market value of its SOMA securities approximately $1 trillion less than their book value, selling these securities would immediately turn huge unrealized mark-to-market losses into actual cash losses. To avoid reporting such embarrassing losses, the Fed has committed to hold these securities until they mature to ‘avoid’ a loss, thus constraining its monetary policy options.

“The Fed’s official plan is to shrink the size of its balance sheet by letting its SOMA securities mature over time. But if interest rates stay elevated, the Fed’s unrealized market value losses will systematically turn into cash operating losses because the Fed will keep paying more to finance its securities than the yield it earns on SOMA securities. FRBs’ operating losses could continue for a long time.”

The bottom line is that the Fed, as Emperor of monetary policy, has threadbare garments. It’s left with only a confidence game. Kupiec and Pollock explain that as follows:

“As long as the public and financial market participants retain confidence in the FRB’s unsecured deposits, FRBs [Federal Reserve Banks] can continue to pay banks billions in interest and dividend payments while operating at a loss, deeply technically insolvent, and with asset shortfalls. Aided by an implicit guarantee, taxpayers will bear the burden of accumulating Federal Reserve losses that are hidden by Federal Reserve accounting policies and not included in reported government deficit statistics.”

Maintaining confidence in the Fed has already come at a serious price, including censored reporting by mainstream media. That’s something the American people should think about very carefully. (See There’s a News Blackout on the Fed’s Naming of the Banks that Got Its Emergency Repo Loans; Some Journalists Appear to Be Under Gag Orders. See also: Reporters Who Ask Tough Questions at Fed Press Conferences Have a Habit of Being Disappeared from the Room.)