By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: September 25, 2023 ~

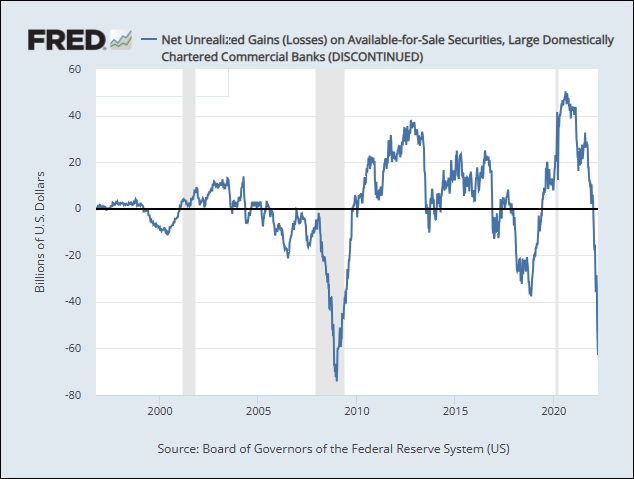

On March 30, 2022, two highly troubling events occurred: (1) Fed data showed that unrealized losses on available-for-sale securities at the 25 largest U.S. banks were approaching the levels they had reached during the financial crisis in 2008; and (2) the Fed simply stopped reporting unrealized gains and losses on these banks’ securities.

As the chart above indicates, the Fed had reported this data series from October 2, 1996 to March 30, 2022 – and then, poof, it was gone and could no longer be graphed weekly at FRED, the St. Louis Fed’s Economic Data website. (See chart above from FRED.) On the same date, the Fed also discontinued the weekly data for unrealized losses or gains on available-for-sale securities at all commercial banks and small banks.)

This data series was halted after the Fed had embarked on March 17, 2022 on the first leg of 11 consecutive rate increases, at the fastest pace in 40 years. The Fed took its benchmark Fed Funds rate from 0.00 – 0.25 percent on March 16, 2022 to 5.25 – 5.50 percent by its last rate hike on July 27 of this year.

The Fed had little choice but to hike rates at this speed because the U.S. was facing spiraling inflation pressures.

Unfortunately for U.S. banks, these rate hikes came after the banks had loaded up on low interest rate Treasury securities and federal agency Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS). The banks had loaded up on these securities because their deposit balances had swollen to an historic level as a result of the trillions in stimulus payments that the federal government direct-deposited into depositor accounts at banks to deal with the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic and related business closures negatively impacted business loan demand so banks turned to government-backed bonds as a safe place to park the trillions of dollars in extra deposits.

In hindsight, of course, parking large amounts of a bank’s deposits in bonds yielding next to nothing is not a rational move for the long term. Not hedging the interest rate risk on the bonds was an equally precarious move by so-called risk managers at the bank. (See Study Finds 75 Percent of U.S. Banks Didn’t Hedge Interest Rate Risk; Unrealized Losses on Securities $516 Billion at End of First Quarter.)

As interest rates rise, the market value of bonds issued with much lower fixed interest rates lose market value. That’s because those bonds pay less interest than the newer bonds with higher fixed rates of interest and thus have less desirability to investors. This effect is expressed this way: bonds have an inverse relationship to interest rates.

Since this formula is one of the first things that a rookie trader learns at a bond trading desk, why would banks think they could just skip the cost of hedging this massive risk?

To fully appreciate what big banks have been getting away with since they crashed the U.S. economy in 2008, let’s take a look at what Citigroup reported on its 10-K (annual report) filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for the last quarter of 2008: (See page 160 at this link.)

“SFAS 115 requires transfers of securities out of the trading category be rare. Citigroup made a number of transfers out of the trading and available-for-sale categories [to the held-to-maturity category] in order to better reflect the revised intentions of the Company in response to the recent significant deterioration in market conditions, which were especially acute during the fourth quarter of 2008…

“The December 31, 2008 carrying value of the securities transferred from Trading account assets and available-for-sale securities was $33.3 billion and $27.0 billion, respectively. The Company purchased an additional $4.2 billion of held-to-maturity securities during the fourth quarter of 2008, in accordance with prior commitments.”

At the end of the fourth quarter of 2008, Citigroup had swelled its held-to-maturity securities to a carrying value of $64.46 billion and had this to say about the transfers into the held-to-maturity category:

“The net unrealized losses classified in accumulated other comprehensive income that relates to debt securities reclassified from available-for-sale investments to held-to-maturity investments was $8.0 billion as of December 31, 2008…This will have no impact on the Company’s net income, because the amortization of the unrealized holding loss reported in equity will offset the effect on interest income of the accretion of the discount on these securities.”

For the basket case condition of Citigroup at the end of 2008, see our report at the time: The Rise and Fall of Citigroup.

Moving securities around in a shell game to disguise ongoing losses is not what most Americans want at federally-insured banks backstopped by the U.S. taxpayer.

Under a highly controversial accounting rule, held-to-maturity (HTM) debt instruments are not marked to market or shown on the bank’s balance sheet at fair value, but are instead listed at amortized cost – effectively what was paid for the debt instrument at the time of its purchase, even if its current market value is 20 or 30 percent (or an even greater percentage) below its original cost.

The HTM accounting treatment is allowing banks to create an illusion on their balance sheet as to what their assets are worth. The bigger the dollar amounts held as HTM investment securities, the bigger the illusion. (While fair value for HTM securities and unrealized losses are provided in supplemental charts in SEC filings, the fair value is not reflected in the asset value on the balance sheet itself – leaving the average shareholder clueless as to what the bank’s assets are actually valued at by the market.)

The largest bank in the U.S., JPMorgan Chase, has transferred massive amounts of securities into the held-to-maturity category. According to JPMorgan Chase’s 10-K for the period ending December 31, 2022, it was holding $425.3 billion in HTM securities, which actually have a fair market value of just $388.6 billion or an unrealized loss of $36.7 billion.

Raising more red flags, most of these debt instruments were not designated as HTM at time of purchase, which they are supposed to be, but were transferred to that category in 2020, 2021, and 2022. (See our report: JPMorgan Chase Transferred $347 Billion in Debt Securities Over the Last 3 Years to Inflate Its Capital Using a Controversial Maneuver.)

Despite this hubris, the Chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase, Jamie Dimon, is leading the attack on federal regulators who want to increase capital levels at banks with $100 billion or more in assets in order to protect the safety and soundness of the U.S. banking system.

To get a handle on these unrealized losses across the banking industry, one has to now wait on the FDIC’s Quarterly Banking Profile instead of being able to go to FRED weekly and graph the situation. (Individual banks report the unrealized losses or gains in their quarterly call reports as well as on their 10-Q quarterly filings with the SEC. But a lot of nasty stuff can happen in the span of three months, as Americans learned earlier this year when the second, third and fourth largest bank failures in U.S. history occurred.)

According to the FDIC, as of June 30, 2023, “Unrealized losses on securities totaled $558.4 billion in the second quarter, up $42.9 billion (8.3 percent) from the prior quarter. Unrealized losses on held-to-maturity securities totaled $309.6 billion in the second quarter, while unrealized losses on available-for-sale securities totaled $248.9 billion.”

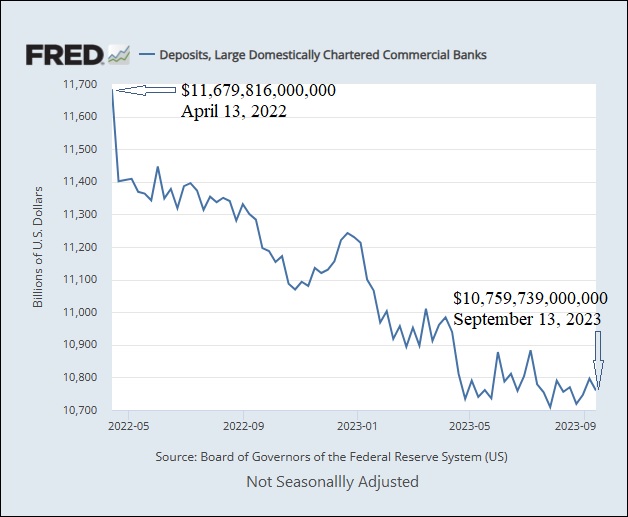

Adding to the stresses at the 25 largest banks, their deposits have fallen by $920 billion since April 13, 2022. (See chart below.) This is a result of some of their uninsured deposits taking flight because of the lingering fears caused by the bank failures this year; competition from higher interest rates being offered by smaller competitors; and the attractiveness of short-term U.S. Treasury securities that now yield over 5 percent.