By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: July 11, 2023 ~

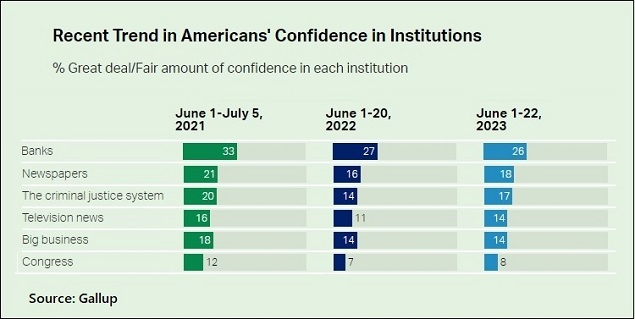

The polling organization, Gallup, conducted a survey between June 1-22 to update its annual poll that measures the confidence that Americans have in key U.S. institutions. Banks, as might be expected, continued their downward trend, registering an abysmal 26 percent of Americans who have “a great deal” or “fair amount” of confidence in the banks. That confidence ranking stood at 27 percent last year and at 33 percent in 2021.

The polling organization, Gallup, conducted a survey between June 1-22 to update its annual poll that measures the confidence that Americans have in key U.S. institutions. Banks, as might be expected, continued their downward trend, registering an abysmal 26 percent of Americans who have “a great deal” or “fair amount” of confidence in the banks. That confidence ranking stood at 27 percent last year and at 33 percent in 2021.

It is actually somewhat baffling that confidence in banks only dropped by one percentage point from last year, given that the second, third and fourth largest bank failures in U.S. history occurred in the first half of this year.

Measured against a longer time horizon, confidence in U.S. banks looks far worse. In 1979, the Gallup poll showed 60 percent of Americans had confidence in the banks. In the years prior to the Wall Street financial crisis of 2008, roughly half of Americans had confidence in the banks. The 2008 crisis pulled back the dark curtain that had surrounded the mega banks on Wall Street, revealing them to be trading casinos on steroids, in drag as federally-insured banks.

The repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999 by the Wall Street friendly Bill Clinton administration was a watershed moment in its impact on all of the following in America: national security, the safety and soundness of the banking system, the ability of Americans to believe in their government to act honestly and fairly, the rise of the billionaire class, and with it, the greatest wealth inequality in U.S. history.

The Glass-Steagall Act was passed by Congress at the height of the Wall Street collapse that began with the 1929 stock market crash, the ensuing insolvency and closure of thousands of banks, followed by the Great Depression. The legislation addressed two equally critical flaws in the U.S. banking system of that time. It created, for the first time, federally-insured deposits at commercial banks to restore the public’s trust in the U.S. banking system and it barred commercial banks that were holding those newly-insured deposits from being part of Wall Street’s trading casinos – the brokerage firms and investment banks that were underwriting and/or trading in stocks and other speculative securities.

As a result of the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act (also known as the Banking Act of 1933), trading casinos on Wall Street like JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, and Morgan Stanley are allowed to own federally-insured commercial banks (and do own them) and hold trillions of dollars (yes, trillions) of complex and hard to price derivatives inside the insured banks.

By allowing mega banks to make high-stake trading gambles using federally-insured deposits (or, even worse, bankroll insanely ginned up derivatives at hedge funds), federal bank regulators have guaranteed that there will be a non-stop series of banking crises that continue to undermine the public’s trust in the banks. (See our report from April 20: Former New York Fed Pres Bill Dudley Calls This the First Banking Crisis Since 2008; Charts Show It’s the Third.)

For a deeper dive into the banking trainwreck that has ensued since the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, we highly recommend the brilliant book by Arthur E. Wilmarth, Jr., Taming the Megabanks: Why We Need a New Glass-Steagall Act.

It should trouble every American that a major newspaper in the U.S., which just happens to be located in Wall Street’s hometown, used its editorial page to lobby for the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act. The New York Times began to wave its pom poms for the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1988, writing as follows about the 1929 crash:

“Few economic historians now find the logic behind Glass-Steagall persuasive. Banks did lose some money in the crash, but largely through defaults of loans secured by stock. Restrictions on investors’ ability to buy stock on credit would have helped to protect the banks, but not the Glass-Steagall prohibitions on selling or underwriting securities.”

That statement stands as a complete contradiction of the findings of the 3-year Senate investigation into the causes of the 1929-1932 crash. Investigators found that the Wall Street banks that were underwriting securities were also creating “pool operations” where they coordinated pumping up share prices until they could sell at a big profit. This created an artificially inflated market and undermined the safety and soundness of their banks, which also held savings deposits.

In 1990 the Times again attacked the Glass-Steagall Act, writing:

“The Glass-Steagall Act was passed in part to settle a turf war between competing interests in U.S. financial markets. But it also reflected a belief, fueled by the 1929 crash on Wall Street and the subsequent cascade of bank failures, that banks and stocks were a dangerous mixture.

“Whether that belief made sense 50 years ago is a matter of dispute among economists. But it makes little sense now…”

Smelling victory in its long push to repeal the Glass-Steagall Act, on April 8, 1998 the New York Times editorial page slobbered over what would become one of the worst banking mergers in U.S. history, and one that it knew would force the hand of Congress to repeal Glass-Steagall. The Times wrote:

“Congress dithers, so John Reed of Citicorp and Sanford Weill of Travelers Group grandly propose to modernize financial markets on their own. They have announced a $70 billion merger — the biggest in history — that would create the largest financial services company in the world, worth more than $140 billion… In one stroke, Mr. Reed and Mr. Weill will have temporarily demolished the increasingly unnecessary walls built during the Depression to separate commercial banks from investment banks and insurance companies.”

The merger went through and one year later, in 1999, the Bill Clinton administration repealed the Glass-Steagall Act. Just nine years later, Wall Street collapsed in the same epic fashion as 1929, leaving the U.S. economy in shambles. Citigroup became a 99-cent stock in early 2009 while receiving the largest bailout in U.S. banking history from December 2007 through at least June of 2010.

On July 27, 2012, the New York Times sheepishly owned up to its role in helping to crater Wall Street and confidence in the banks. The editorial page editors wrote:

“While we are on this subject, add The New York Times editorial page to the list of the converted. We forcefully advocated the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act…

“Having seen the results of this sweeping deregulation, we now think we were wrong to have supported it.”

One might be inclined to consider that gesture by The Times as too little, too late.

Speaking of which, Americans’ confidence in newspapers is even lower than is their confidence in the banks. According to the 1979 Gallup poll, 51 percent of Americans had confidence in newspapers. In the current 2023 Gallup poll, that figure stands at 18 percent. The only institutions with a lower rating are: the criminal justice system at 17 percent; television news at 14 percent; big business at 14 percent; and Congress at 8 percent, just one percent above its all-time low of 7 percent, which it clocked in at last year.

Until the Glass-Steagall Act is restored in the United States, the frequency and severity of banking crises will grow. Tinkering around the edges of capital reform, or stress test reform, as Fed Vice Chair for Supervision Michael Barr delivered a speech about yesterday, is a fool’s errand.