By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: March 27, 2023 ~

On Sunday, Financial Times reporters Brooke Masters, Harriet Clarfelt and Kate Duguid published an article under the headline: “Money market funds swell by more than $286bn as investors pull deposits from banks.”

This article needs some important clarifications. First is the fact that money market funds had to be bailed out by the government during both the 2008 financial crisis and the more recent financial panic of 2020 stemming from the COVID pandemic.

On September 19, 2008 (four days after Lehman Brothers was placed into bankruptcy), stocks were crashing and investors were in a panic, the Department of the Treasury announced that it would provide a guarantee for money market mutual funds, standing behind more than $3.5 trillion in money market fund assets.

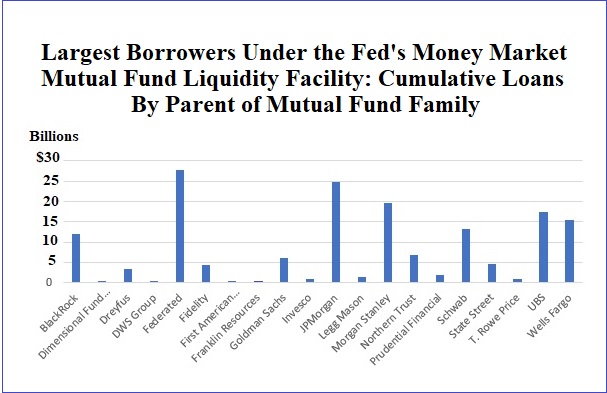

In mid-March 2020, as the share prices of mega banks on Wall Street were plunging in price and investors were in another panic, the Federal Reserve, with the required approval of the U.S. Treasury Secretary for emergency bailout programs from the Fed, established the Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF). Under the facility, the Boston Fed made loans to various banks to purchase troubled assets from money market funds. When the Fed finally released the details of that program, Wall Street On Parade crunched the numbers and found that just six Wall Street firms received 72 percent of the $162.9 billion in cumulative loans made under the MMLF. The three largest recipients were Federated, JPMorgan Chase and Morgan Stanley. (See our full report here.)

Most Americans are unaware that there are two vastly different kinds of money market vehicles. There is the “money market account” that one can hold at a federally-insured bank which is FDIC-insured up to $250,000 per depositor per bank. If you have multiple FDIC-insured accounts at the same bank (money market account, checking, savings, certificates of deposit), they all count toward the $250,000 insurance limit.

There is also the “money market fund” which is an uninsured mutual fund packed with short-term debt instruments of varying quality.

It was these uninsured money market funds that had to be bailed out during the 2008-2009 financial crisis on Wall Street and again during the March 2020 financial panic related to the COVID pandemic.

The Financial Times article is talking about the uninsured money market funds.

So why would Americans be flocking to these uninsured money market funds during the latest banking panic?

We found our answer in the data released by the Investment Company Institute (ICI.org). According to ICI’s statistics, $276.49 billion of that $286 billion reported by the Financial Times (or a whopping 97 percent), went into a very specific type of money market fund – the kind that holds short-term debt instruments guaranteed by the U.S. government. These are referred to as “government money market funds.”

ICI reports that total assets in Government Money Market Funds grew as follows in the month of March: total assets of $3.98 trillion as of March 9, 2023; total assets of $4.128 trillion as of March 15, 2023; total assets of $4.26 trillion on March 22, 2023.

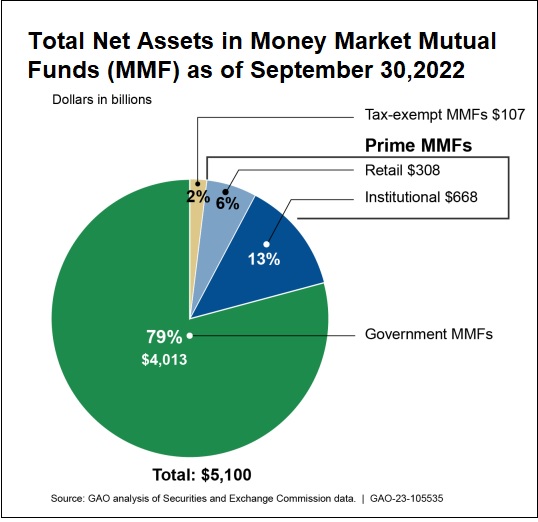

According to the ICI’s latest data, Government Money Market Funds in the U.S. now represent 83 percent of all money market funds. As of March 22, 2023, Government Money Market Fund assets of $4.26 trillion compared to total assets in all money market funds of $5.13 trillion. According to a report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO), Government Money Market Mutual Funds represented 79 percent of all money market funds as of September 30, 2022. (See chart below.)

This flight to safety is having an unintended consequence. It is throwing a wrench in the Federal Reserve’s plans to bring down inflation in the U.S. by hiking its benchmark interest rate. For example, the 6-month U.S. Treasury bill, which had traded at a yield of 5.29 percent in early March, is trading this morning at a yield of 4.85 percent – notwithstanding that the Fed raised its benchmark interest rate (Fed Funds) by another one-quarter percent on March 22.

Money market mutual funds are required to hold short-term instruments, typically of less than one year to maturity. Government Money Market Funds hold lots of U.S. Treasury bills, such as the 6-month T-bill. The demand for these government instruments of less than one year maturity, is also likely adding to the inverted yield curve, where short-term government securities are yielding significantly more than the 30-year U.S. government bond.