By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: October 7, 2022 ~

Nomura Holdings is tiny compared to the mega banks on Wall Street. According to its website, it had just $384 billion in assets as of March 31, 2021. On the same date, JPMorgan Chase had $3.2 trillion in assets. But for reasons that neither the Federal Reserve nor Congress have yet to explain, a unit of Nomura was allowed to borrow trillions of dollars in emergency repo loans from the Fed beginning on September 17, 2019 – months before there was any COVID crisis anywhere in the world.

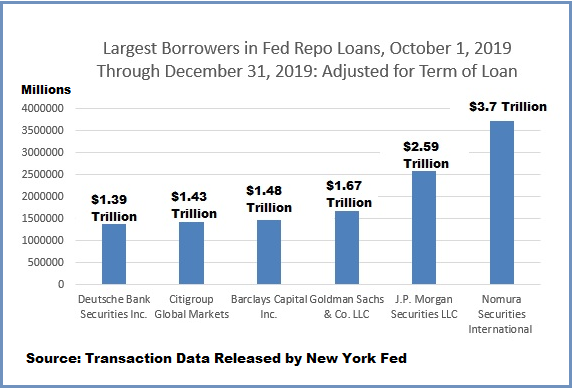

The chart above shows that in the last three months of 2019, Nomura borrowed $3.7 trillion cumulatively under the Fed’s emergency repo loan program, topping the amount borrowed by JPMorgan Chase by $1.11 trillion. The loan amounts come directly from the emergency repo loan data being released quarterly by the New York Fed, adjusted for the term of the loan. (Reverse repo amounts have to be deleted from the data released by the Fed.)

The Fed swung into emergency mode on September 17, 2019 when the rate on overnight repo loans suddenly spiked from around 2.25 percent to as high as 10 percent at one point, strongly suggesting the street was backing away from questionable borrowers. The Fed set up its own facility to make tens of billions of dollars in loans available to trading houses on Wall Street on a daily basis, and at very cheap interest rates that did not reflect the credit risk of the individual trading houses. (Repos, short for Repurchase Agreements, are a short-term form of borrowing where corporations, banks, brokerage firms and hedge funds secure loans, typically for one day, by providing safe forms of collateral such as Treasury notes.)

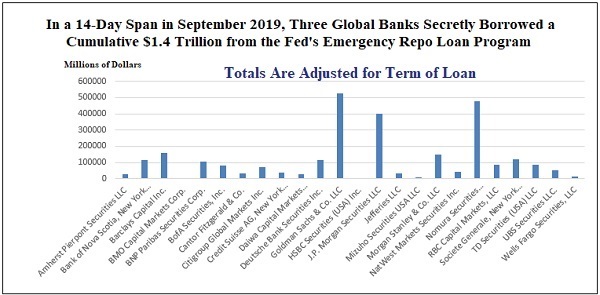

The distress being experienced by Nomura likely came from its large derivatives exposure. The fact that JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs were, from the get-go, also borrowing heavily from the Fed, suggest that the three firms were counterparties to each other’s derivatives. (See 14-day chart below beginning when the Fed first launched its emergency repo loan bailouts.)

Raising more alarm bells, the annual report for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2022 filed with the SEC for Nomura Holdings explains that its U.S. subsidiary, Nomura Global Financial Products Inc., “is an ‘OTC derivatives dealer,’ which is a class of broker-dealer exempt from certain broker-dealer requirements, including membership in an SRO, regular broker-dealer margin rules and application of the Securities Investor Protection Act of 1970, but are subject to special requirements, including limitations on the scope of their securities activities, specified internal risk management control systems, recordkeeping obligations and reporting responsibilities. OTC derivatives dealers are also subject to alternative net capital treatment…” (Italic emphasis added.)

Not being subject to regular margin rules might help to explain why Nomura had to take a $2.9 billion loss when the family office hedge fund, Archegos Capital Management, blew up in March of last year. (See our report: Wall Street Was Effectively Giving 85 Percent Margin Loans on Concentrated Stock Positions – Thwarting the Fed’s Reg T and Its Own Margin Rules.) The loss reported by Nomura in the Archegos blowup was second only to the more than $5 billion loss reported by Credit Suisse.

As of yesterday’s closing prices, the shares of both Nomura and Credit Suisse are trading in the low single digits. In New York trading, Credit Suisse closed at $4.29 while Nomura closed at $3.34. Nomura’s market capitalization has now declined by 38 percent since the end of its last fiscal year on March 31, 2021.

Before the onset of the Fed’s emergency repo bailouts in the fall of 2019, the first since the financial crisis of 2008, Nomura had made alarming revelations in its Consolidated Statement of Financial Condition for Nomura Securities International for the period ending March 31, 2019. (Nomura Securities International was the trading unit taking the loans from the Fed.) The financial statement shows that Nomura Securities International had total assets of $127.5 billion but potential derivative exposure as follows: (See pages 30 and 41.) A “Maximum Payout” on protection sold on credit derivatives of $14 billion; and a “Maximum Payout” on “derivative contracts that could meet the definition of a guarantee” of $97.7 billion.

In April of 2019 the parent company, Nomura Holdings, announced it would need to cut $1 billion in costs and close more than 30 of its 156 retail branches in Japan. It had just suffered its first full-year loss in a decade.

Less than three months after Nomura Securities International had begun to take giant secret loans from the Fed’s repo facility, Nomura Holdings announced that it had named a new CEO, Kentaro Okuda, who was quoted in the Financial Times as taking charge with a “sense of crisis.”

At the time of the financial crisis in 2008 there was no law that forced the Fed to ever reveal the names of the banks that took emergency loans from the Fed and the amounts borrowed. The Dodd-Frank legislation of 2010 made these disclosures by the Fed a statutory requirement. But Dodd-Frank set up a two-tier level of disclosures. If the emergency lending program was under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, the Fed would have to reveal the names of the borrowers and amounts borrowed one year after the program had been terminated. But emergency operations conducted through the Fed’s so-called “open market” operations would not have to reveal the names of the firms and amounts borrowed until two years after the loans were made. Lorie Logan’s open market desk at the New York Fed made these repo loans, thus the Fed had two years to release the names of the banks and the amounts borrowed.

Stunningly, when that breathtaking information began to be released by the Fed on a quarterly basis beginning on October 1, 2021, there was a total news blackout by mainstream media – despite the fact that some of these same mainstream media had taken the Fed to court for more than two years to obtain the names of the banks and their loan information after the 2008 crash. (See our report: There’s a News Blackout on the Fed’s Naming of the Banks that Got Its Emergency Repo Loans; Some Journalists Appear to Be Under Gag Orders.)

The Federal Reserve Board of Governors in Washington D.C. is an independent federal agency. Unfortunately, it outsources the vast majority of its emergency lending programs to the New York Fed, one of 12 privately owned regional Fed banks. The largest shareowners of the New York Fed are the following five Wall Street banks: JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Bank of New York Mellon. Those five banks represent two-thirds of the eight Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs) in the United States. The other three G-SIBs are Bank of America, a shareowner in the Richmond Fed; Wells Fargo, a shareowner of the San Francisco Fed; and State Street, a shareowner in the Boston Fed.

After we crunched the numbers for the Fed’s emergency repo loans, it appears that the New York Fed may have intentionally thrown in a dizzying array of term loans to this one-day (overnight) repo loan market in order to disguise outsized borrowing by a handful of trading houses.

For example, the New York Fed offered one-day repo loans every business day but periodically also added 14-day, 28-day, 42-day and other term loans. Let us say for example that a trading firm took a $10 billion loan for one-day but on the same day took another $10 billion loan for a term of 14 days. The 14-day loan for $10 billion represented the equivalent of 14-days of borrowing $10 billion or a cumulative tally of $140 billion.

If we had simply tallied the column that the New York Fed provided for “trade amount” per trading firm, it listed only $10 billion for that 14-day term loan and not the $140 billion it actually translated into.

When we tallied the New York Fed’s “trade amount” column for the fourth quarter of 2019, the New York Fed’s repo loans came to $4.5 trillion. But when we set up a new column that adjusted the loans by the number of days in the term, the Fed’s repo loans for the fourth quarter of 2019 came to $19.87 trillion, or 4.4 times the “trade amount” column.

Just six trading houses received 62 percent of the $19.87 trillion, as illustrated in the chart at the top of this page. The parents of three of those firms, JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup and Goldman Sachs, are shareowners of the New York Fed. The largest borrower, Nomura, is a unit of a Japanese firm and is highly likely interconnected as a derivatives counterparty to the major Wall Street banks.

The New York Fed, literally owned by major Wall Street banks, is allowed to electronically create the trillions of dollars it loans to them at the push of a button. (See These Are the Banks that Own the New York Fed and Its Money Button.)

The Fed’s audited financial statements show that on its peak day in 2019, the Fed’s repo loans outstanding stood at $259.95 billion. It should be noted that there was no COVID-19 pandemic crisis in the U.S. in 2019. The first case of COVID-19 in the U.S. was reported by the CDC on January 20, 2020.

As we reported yesterday, the Office of Financial Research – which was created under Dodd-Frank to issue alarms over financial stability risks — has released a report that makes the following findings about Wall Street’s dangerous over-the-counter derivatives:

“In a recent working paper analyzing who banks chose as counterparties in the over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives market, the authors found that banks are more likely to choose riskier nonbank counterparties that are already heavily connected and exposed to other banks, which leads to an even more densely connected network. Furthermore, banks do not hedge these exposures, but rather increase them by selling rather than purchasing credit derivative swaps against these counterparties. Finally, the authors found that common counterparty exposures are correlated with systemic risk measures despite greater regulatory oversight following the 2008 financial crisis.” (Italic emphasis added.)

American taxpayers have every right to demand that members of Congress pull their head out of the sand and hold immediate hearings on this critical topic.