By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: July 7, 2022 ~

The Office of Financial Research (OFR), a unit of the U.S. Treasury Department, was created under the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010. Its job is to prevent, through early warnings, the kind of catastrophic financial crisis that occurred in 2008 when irresponsible and corrupt practices on Wall Street toppled the U.S. economy; brought on the deepest financial crisis since the Great Depression; and left the taxpayer and Fed bailing out the Wall Street megabanks that would have otherwise collapsed from their own hubris.

Unfortunately, the OFR was savagely gutted under the Trump administration. Today, OFR is like the cop on the beat that has been stripped of his whistle, his walkie-talkie and is wearing dark sun glasses on a cloudy day.

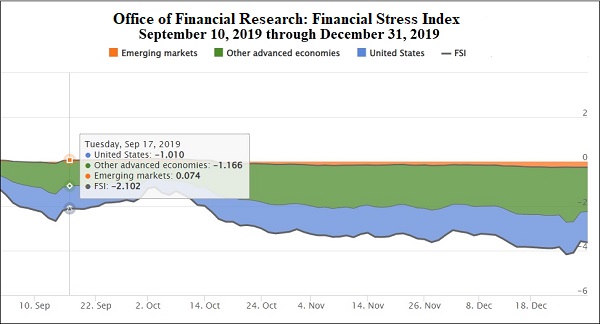

One of the tools that the OFR is supposed to use to warn federal regulators that Wall Street is heading toward another trainwreck is the Financial Stress Index (FSI). This is how the OFR describes that Index:

“The OFR Financial Stress Index (OFR FSI) is a daily market-based snapshot of stress in global financial markets. It is constructed from 33 financial market variables, such as yield spreads, valuation measures, and interest rates. The OFR FSI is positive when stress levels are above average, and negative when stress levels are below average.

“The OFR FSI incorporates five categories of indicators: credit, equity valuation, funding, safe assets and volatility. The FSI shows stress contributions by three regions: United States, other advanced economies, and emerging markets.”

Looking at the Financial Stress Index chart that would have covered the 2008 financial crisis (had the FSI existed at that time) it would appear that the Index is not very good at forecasting what’s ahead, the very purpose of a “forecast.” For example, by September 15, 2008, the day that Lehman Brothers filed bankruptcy, the FSI only had a reading of 10.803. (See chart below.) But at that point in time, the Fed had been secretly bailing out the megabanks and their derivatives counterparties since December 2007, according to the audit requested by Congress from the Government Accountability Office (GAO). In addition, Bear Stearns had blown up in March of 2008; the U.S. government had to put Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae into conservatorship on September 6; and Citigroup, one of the largest banks in the country with trillions of dollars of derivatives on and off its books, was teetering and spreading contagion.

Given this 2008 insight into how the Financial Stress Index is inadequately suited to provide an early heads up to federal regulators, we decided to see what the FSI reading looked like in the leadup to the financial crisis that began on September 17, 2019 that necessitated the Fed making cumulative loans (term adjusted) of $19.87 trillion in the fourth quarter of 2019 to the megabanks on Wall Street.

That chart is even more damaging to the OFR than the chart from 2008. The Financial Stress Index simply slept through the entire crisis of 2019. (See chart at the top of this article.)

Here’s what was actually going on in the fall of 2019 while the Financial Stress Index was measuring below-normal levels of stress: On September 17, 2019 the overnight repo loan rate spiked from an average of about 2 percent to 10 percent – signaling that one or more important Wall Street firms were in trouble. The repo loan market is an overnight loan market where banks, brokerage firms, mutual funds and others make predominantly one-day loans to each other against safe collateral, typically Treasury securities. Repo stands for “repurchase agreement.” When firms back away from lending to each other, someone is in trouble and spreading contagion.

Because the repo market dried up, the Fed effectively became the repo loan market on September 17, 2019 and exponentially grew the amount of emergency repo loans it was making over the following months. And, instead of just making the customary overnight loans, the Fed also added loans lasting for weeks, up to 42-day loans in some cases.

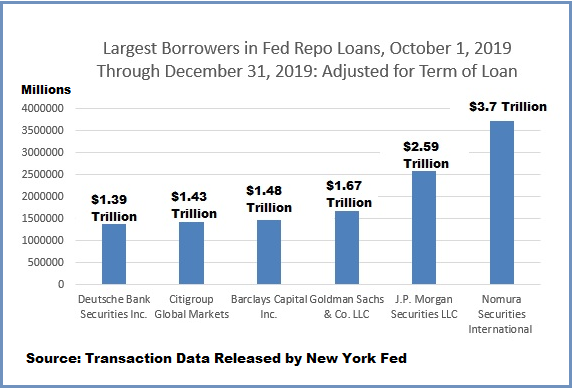

The Fed’s cumulative repo loans for the fourth quarter of 2019 on a term-adjusted basis came to $19.87 trillion based on the data it released two years later. Just six trading houses received 62 percent of the $19.87 trillion, as illustrated in the chart below. If this is not a financial stability crisis, we don’t know what is.