By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: June 9, 2022 ~

On September 14 of last year, we wrote this about SEC Chair Gary Gensler:

“Gensler’s opening remarks at today’s Senate Banking Committee hearing include seven references to this phrase: ‘asked staff for recommendations…’ If past is prologue, this will mean that Gensler will run out the clock on actually advancing any meaningful ‘recommendations’ into concrete final rules.”

Yesterday, Gensler gave a heavily promoted speech about cleaning up the way that retail stock orders are handled on Wall Street. But all the speech actually did was to ask his staff for more ideas and recommendations. The phrase “asked staff” appears 13 times in the speech.

While Gensler spends his time giving speeches and asking his staff for recommendations that don’t go anywhere, large chunks of U.S. markets are blowing up in investor portfolios.

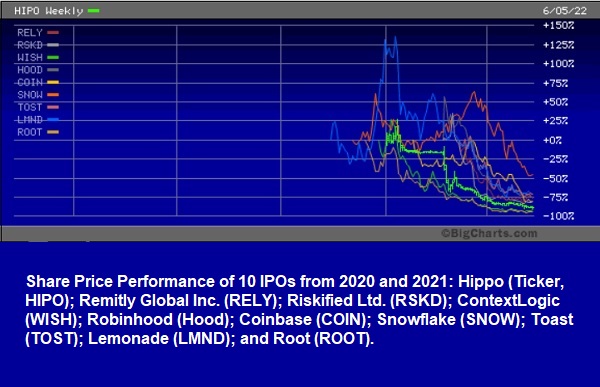

Let’s start with some of the tech startups that the SEC allowed to be listed on U.S. exchanges. Toast’s share price is toast. Snap has snapped. Snowflake has melted. Lemonade handed its shareholders a pile of lemons – that quickly rotted.

If you’re wondering who on earth would attempt to raise large sums from public investors with companies named Toast, Snap, Snowflake, Lemonade, and Hippo, you’ve apparently been blessed with a safe distance from Wall Street.

Toast describes itself to its restaurant customer base like this: “Take control of changing guest expectations with online ordering, delivery, contactless order & pay, e-gift cards, email marketing and more.” Toast began trading on the New York Stock Exchange on September 22, 2021. Its lead underwriters were Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan. Its IPO shares were priced at $40 and closed on their first day of trading at $62.51 – a 56 percent surge in one day. But after the lockup period for insiders to dump their shares ended, the stock began its steady downward descent. Toast closed yesterday at $16.23, a loss of 59 percent from its offering price and a loss of 74 percent from its first-day closing price.

Bottom line: insiders got a windfall from IPOs; Wall Street underwriters collect a lucrative fee; Big Law gets billable hours; and public investors frequently get fleeced.

Take the case of Coinbase, a cryptocurrency exchange that America needs about as much as it needs another social media platform. Coinbase went public on Nasdaq via a direct listing on April 14, 2021. On its first day of trading, it closed at a share price of $328.28, giving it a market capitalization of $85.8 billion. (That’s $31 billion more than the current market cap of Ford Motor Company, a company that has been reliably producing automobiles for more than a century and has one of the most popular electric trucks on the market – the F-150 Lightning.)

In a traditional IPO, early investors and company executives are not allowed to sell their shares for several months due to a so-called lockup period. There’s no such restriction in a direct listing. According to an SEC filing, Coinbase’s Chairman and CEO, Brian Armstrong, sold 750,000 shares on April 14, 2021 at an average share price of $389.10, or approximately $291.8 million in total. Since then, Coinbase’s share price has been on a steady descent. It closed yesterday at $69.20 — a decline of 82 percent from where its CEO exited on the first day of trading.

On May 24 of last year, the House Financial Services’ Subcommittee on Investor Protection, Entrepreneurship and Capital Markets held a hearing on shady dealings in the IPO (Initial Public Offering) market in the U.S. The hearing was titled: “Going Public: SPACs, Direct Listings, Public Offerings, and the Need for Investor Protections.” Unfortunately, we have been watching the SEC and Congress fail to meaningfully reform this thinly-veiled institutionalized wealth transfer system for almost four decades.

One witness at the hearing was Andrew Park, the Senior Policy Analyst for the Wall Street watchdog, Americans for Financial Reform. In his written testimony, Park had this to say about SPACs, also known as blank-check companies:

“Although many people have just started hearing about these SPACs recently, SPACs are far from new. In fact, they date back to the 1980s when they were called blank check companies and often associated with scams, bilking unsuspecting investors out of millions of dollars. Fraud was so pervasive in these blank check companies that Congress passed the Penny Stock Reform Act (PSRA) in 1990 to address some of the problems, which was followed by the SEC putting in place Rule 419 for blank check companies. Blank check company issuers, however devised the modern-day SPAC structure to get around those rules, reminding us that properly regulating new assets requires continuing attention and action.”

SPACs (Special Purpose Acquisition Companies) are allowed to tap the public markets with an IPO when they have no business operations at all and simply plan to eventually acquire an existing company. This insanity is allowed in U.S. markets. How can underwriters properly disclose to investors the business risks of this new offering in their public SEC filings when there actually is no business to describe?

According to FactSet, if you include SPACs and all types of IPOs, the total amount raised in 2020 through IPOs was $174 billion – which was a 150 percent increase over 2019. FactSet notes that SPACs accounted for half of all IPOs in 2020.

SPAC-alypse increased in 2021. According to FactSet, through mid-December 2021, there had been 1,017 IPOs listed on U.S. exchanges, the largest number by far in its records dating back to 1995. (The previous record for IPOs was 664 in 1996. That dot.com era ended with Nasdaq losing 78 percent of its value from peak to trough.) FactSet says that SPACs represented 53.1 percent of 2021’s IPOs and 45.8 percent of the money raised in 2021 through mid-December.

The total amount raised from IPOs in 2021 grew from $174 billion in 2020 to more than $300 billion in 2021. SPACs accounted for more than $137 billion raised in 2021 according to FactSet.

The chart above shows how 10 of the IPOs from 2020 and 2021, that were promoted with the sexy appeal of new technology, have performed.

The last two years of the IPO market in the U.S. has been simply a repackaged version of the same brand of hype that Wall Street deployed during the dot.com wealth transfer scheme that enriched insiders and Wall Street underwriters while fleecing unsophisticated investors and public pension funds.

What Main Street needs is an SEC with criminal prosecution powers (it only has civil powers), a tough cop on the beat as SEC Chair, and a lot less speechifying.