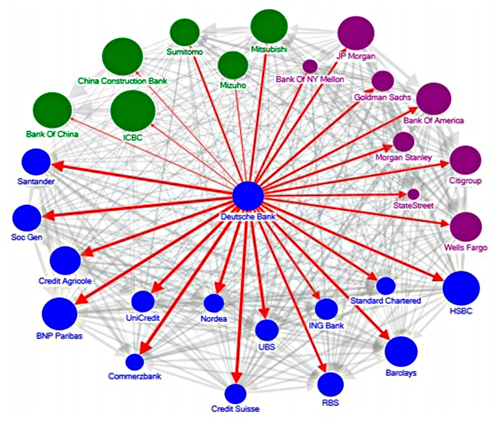

Systemic Risk Among Deutsche Bank and Global Systemically Important Banks (Source: 2016 IMF Report — “The blue, purple and green nodes denote European, US and Asian banks, respectively. The thickness of the arrows capture total linkages (both inward and outward), and the arrow captures the direction of net spillover. The size of the nodes reflects asset size.”)

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: January 7, 2022 ~

Nine days ago the Fed released the names of the Wall Street trading houses that had borrowed a cumulative total of $4.5 trillion in emergency repo loans from the Fed during just the last quarter of 2019. From September 17, 2019 through July 2, 2020, the same banks had borrowed a cumulative total of $11.23 trillion. The Fed is slowly doling out the names of the banks and the specific amounts borrowed on a quarterly basis, after eight quarters of time has elapsed. The Fed is only releasing the information because the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010 made it a legal obligation of the Fed to do so. The Fed had fought a multi-year court battle with the press after the 2008 financial crisis to keep its secret bailouts to Wall Street firms hidden from the American people.

Strange as it may seem, the same press outlets that battled the Fed in court following the 2008 financial crisis to get the names of the banks and the amounts borrowed, have this time around invoked a total news blackout on publishing the names of the banks.

One of the large borrowers under this 2019-2020 Fed facility was not even a U.S. bank. On October 8, 2019 the Fed conducted a one-day (overnight) repo loan operation, offering $37.5 billion. Deutsche Bank Securities, a unit of the giant German bank, took two lots totaling $7.5 billion. On the same day, Deutsche Bank Securities took another $3 billion of a 14-day term repo loan offered by the Fed, bringing its total borrowing from the Fed on just that one day to $11.5 billion. But the 14-day term loan that Deutsche Bank Securities had previously taken on September 27 for $3 billion had not yet expired, so it actually had an outstanding Fed loan balance at that point of $14.5 billion.

The Fed, the U.S. central bank, was making loans of this size (although they were collateralized) to the trading unit of a serially troubled foreign bank.

October 8, 2019 was just 13 days after Deutsche Bank’s headquarters in Frankfurt, Germany were raided by police for the second time in less than a year. The police were probing a vast money laundering operation in Europe. On January 30, 2017, Deutsche Bank was fined a total of $630 million by U.S. and U.K. regulators over claims it had laundered upwards of $10 billion on behalf of Russian investors.

This was not a propitious time for Deutsche Bank to be splashing about in the headlines over having its headquarters raided again. It was one of the largest derivative counterparties (taking the other side of derivative trades) to some of the largest systemically important banks in the world, including the largest U.S. banks.

In June 2016, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) released a report that found that Deutsche Bank posed the greatest threat to global financial stability than any other bank because of its interconnections to Wall Street mega banks and large banks in Europe. As the graph above illustrates, many of the banks showing the largest interconnectedness with Deutsche Bank were the identical banks whose trading units were borrowing from the Fed’s emergency repo loan facility in 2019 and 2020.

But the raid on the headquarters of Deutsche Bank and the money laundering probe were far from the end of Deutsche Bank’s problems. The bank was having serious financial difficulties. Its attempt to merge with Commerzbank had fallen through in April 2019. On July 7, 2019 it announced a plan to fire 18,000 workers and had plans to create a good bank/bad bank, moving its toxic assets that it hoped to sell to the bad bank. Deutsche Bank had also reported losses in three of the prior four years. Its share price had lost 90 percent of its value over the prior dozen years and was trading close to an historic low in September of 2019 when the Fed’s emergency repo loans appeared out of nowhere for the first time since the financial crisis of 2008.

The Monday after the emergency repo loan operations began, Deutsche Bank announced that it would be moving clients and staff from its prime broker unit (that makes loans to hedge funds) to BNP Paribas along with its electronic trading operations.

As the chart above shows, JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank in the United States, was heavily interconnected to Deutsche Bank. Any fallout from problems at Deutsche Bank were going to have “net spillover” to JPMorgan Chase.

JPMorgan Chase’s trading unit, J.P. Morgan Securities, became one of the largest borrowers under the Fed’s emergency repo loan facilities in 2019. We won’t know what happened in 2020 until the Fed begins releasing the names of the banks and dollar amounts borrowed on or about March 31 of this year.

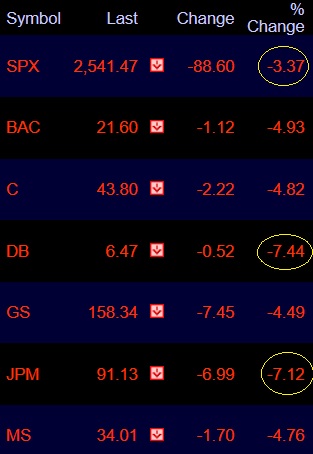

There was also a correlation between the plunging price of JPMorgan Chase’s share price and Deutsche Bank’s plunging share price during some of the worst trading sessions in March 2020. For example, the chart below shows that on Friday, March 27, 2020, the S&P 500 closed down only 3.37 percent while the shares of both JPMorgan Chase and Deutsche Bank lost over 7 percent – which was far in excess of JPMorgan’s peer banks, Bank of America (ticker, BAC), Citigroup (ticker, C), Goldman Sachs (ticker, GS) and Morgan Stanley (ticker, MS).

Despite what was obvious to anyone watching stock charts, Fed Chair Jerome Powell repeatedly testified to the Senate Banking Committee that the U.S. megabanks were “a source of strength” during the financial crisis in 2020.

In the first six months of 2019, long before there was a pandemic anywhere in the world, Reuters reported that JPMorgan Chase had reduced the reserves it was holding at the Fed by $158 billion, or an alarming 57 percent. To this day, no one knows what JPMorgan Chase needed that money for or why the Fed let it draw down those reserves.

The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, the official government body that examined the underpinnings of the 2008 implosion on Wall Street, said this about the role of derivatives in the crisis: “the existence of millions of derivatives contracts of all types between systemically important financial institutions—unseen and unknown in this unregulated market—added to uncertainty and escalated panic, helping to precipitate government assistance to those institutions.”

Despite this acknowledgement that derivatives played a central role in the worst financial crisis in 2008 that the U.S. had seen since the Great Depression, neither the Fed, nor Congress, nor the banking regulators have stopped these banks from holding tens of trillions of dollars of derivatives with questionable counterparties on the other side. Even worse, in the U.S., the derivatives are held at the federally-insured banking units of the megabanks, which are holding deposits for moms and pops across America.