By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: April 30, 2021 ~

During Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell’s press conference this past Wednesday, he took a question from Brian Cheung of Yahoo Finance. The question was: “It seems like to people on the outside who might not follow finance daily, they’re paying attention to things like GameStop, now Dogecoin. And it seems like there’s interesting reach for yield in this market to some extent — also Archegos. So, does the Fed see a relationship between low rates and easy policy to those things, and is there a financial stability concern from the Fed’s perspective at this time?”

As part of Powell’s long, meandering answer, he said this: “Leverage in the financial system is not a problem.” Within a second or so, Powell repeated himself: “Leverage in the financial system is not an issue.” (Read the full transcript here.)

Either Powell has not read any of the quarterly reports coming out of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), a Federal regulator of national banks, or he’s willfully misleading the American people.

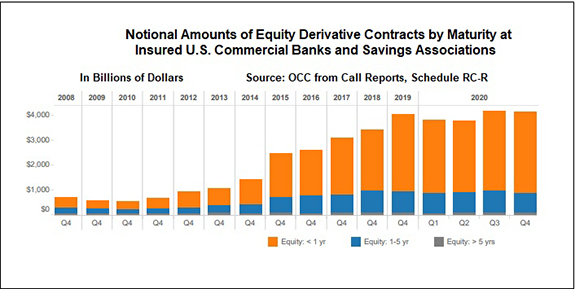

According to the OCC’s most recent “Quarterly Report on Bank Trading and Derivatives Activities,” for the quarter ending December 31, 2020, equity (stock) derivative contracts at federally-insured banks and savings associations have exploded from $737 billion (notional or face amount) since the Wall Street banks last blew themselves up in 2008 to $4.197 trillion notional as of December 31, 2020. That’s a staggering increase of 469 percent in just 12 years.

Equally troubling, the OCC specifically notes that these equity derivative contracts are being held in the federally-insured banks – not at their investment banking units. That means the U.S. taxpayer will be on the hook if these derivatives blow up, as the banks’ previous reckless subprime derivative gambles did in 2008.

But here’s the really dangerous and outrageous part of this. The OCC notes on page 10 of this report that “The four banks with the most derivative activity hold 88.4 percent of all bank derivatives.” In other words, four banks out of 4,989 U.S. banks are putting the entire system at risk.

Graph 10 of the same report provides the answer to just which four banks the OCC is talking about: JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Citigroup’s Citibank, and Goldman Sachs.

Yes, it’s true that Goldman Sachs is allowed to own a federally-insured bank called Goldman Sachs Bank USA. That’s where it has chosen to hold $42.2 trillion notional in various derivative contracts, including equity derivative contracts according to the OCC.

While Goldman Sachs Bank USA is rather small in terms of deposits, holding just $220.7 billion in deposits as of June 30, 2020 according to the FDIC, the other three banks, JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and Citigroup’s Citibank, rank in the top four of the largest federally-insured banks in the United States in terms of deposits, holding a combined $4.8 trillion. (The other large bank by deposits is Wells Fargo. Its exposure to derivatives is exponentially less, however, than the three other banks.)

As the chart above indicates, while the Fed, the regulator of bank holding companies, has been assuring the American people that these banks are “a source of strength,” and that leverage “is not a problem” in the banking system, the casino has been providing massive leverage to all sorts of questionable, highly leveraged hedge funds.

The public learned through the recent implosion of the family office hedge fund, Archegos Capital Management, that Wall Street banks have been effectively loaning out their balance sheets to hedge funds by writing equity derivative contracts that provide a multitude of benefits to the one percent while putting the American taxpayer at risk of another massive bank bailout.

The equity derivative contracts, called swaps, hide the true ownership of the stocks (equities) for reporting purposes. The banks’ 13F filings with the SEC list the stocks as if they are owned by the banks when, in fact, the contract provides both the upside and downside in the stocks’ share price performance to the hedge fund, while the banks collect lucrative fees.

This highly problematic derivative contract does three other things as well: it allows the banks to avoid the Volcker Rule that bans them from owning a hedge fund while still letting them loan out their balance sheet to a hedge fund; it allows them to ignore the Federal Reserve’s Regulation T, which limits them to an initial margin loan of no more than 50 percent of the purchase price of the stock; and it allowed the banks to ignore their own internal broker-dealer rules on loaning against concentrated stock positions. There is also the riveting question of just who was paying the capital gains taxes on these stock trades. (See Did Archegos, Like Renaissance Hedge Fund, Avoid Billions in U.S. Tax Payments through a Scheme with the Banks?)

According to media reports, Archegos may have leveraged up $10 billion of its own equity to as much as $100 billion in stock positions at the banks. When Archegos couldn’t meet its margin calls, the banks had to panic sell the stocks they were holding, pushing down the prices of the stocks in some cases by as much as 50 percent.

Thus far, banks have reported a combined $10.4 billion in losses related to their dealings with Archegos.

And Archegos is just one small dot in a giant matrix. James Beech, writing for CampdenFB in 2019, put “the total estimated assets under management of family offices” at $5.9 trillion with 3,100 of those family offices in North America. He estimates that there are “7,300 single family offices worldwide.”

The Fed has increasingly become the bank supervisor that lives in a dream world of its own fictions. Former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan’s flaky theory was that Wall Street bank executives would look out for the good of the country because it was in their own interests to do so. That theory led to the greatest Wall Street crash in 2008 since the Great Depression. When questioned in a House hearing about the Fed’s myopia as the problems escalated within the banks, Greenspan offered the millions of jobless and homeless Americans this explanation: “I got it wrong.”