By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: December 4, 2020 ~

On November 24 the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) fined JPMorgan Chase $250 million for wrongdoing that was apparently too deplorable to be spoken out loud to the public. The specific details were cloaked in this phrase: “failure to maintain adequate internal controls and internal audit over its fiduciary business.”

We went to the OCC’s Consent Order connected to the fine to see if there were the typical smoking gun internal emails or at least some clue as to what the actual illegal activity was. There were zero clues, just more obfuscation. What we did see, however, was a dollar figure that popped our eyes wide open. The OCC Consent Order said this:

“The Bank maintains one of the world’s largest and most complex fiduciary businesses with total fiduciary and related assets of $29.1 trillion, including $1.3 trillion in fiduciary assets and $27.8 trillion of non-fiduciary custody assets.”

To put that $29.1 trillion into the proper perspective, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) is reporting that as of November 30 of this year, there were a total of 5,031 federally-insured banks and savings associations in the United States. The amount of assets held by all 5,031 of these financial institutions was $21 trillion — $8 trillion less than JPMorgan Chase has in custody assets.

JPMorgan Chase is the largest bank in the United States. To put the $29.1 trillion into even sharper focus, JPMorgan Chase Bank N.A., according to the FDIC, has a total of just $2.87 trillion of its own assets. But, somehow, it has managed to attract more than 10 times its own assets on a custodian basis.

If the idea of numbered Swiss bank accounts is floating around in your brain right now, you can be forgiven.

In September, when the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) released a bombshell investigative report about money laundering for criminals at some of the largest Wall Street banks, it had quite a bit to say about JPMorgan Chase. (The ICIJ investigation was based on secret documents leaked from FinCEN, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, a unit of the U.S. Treasury.)

According to the ICIJ report, JPMorgan Chase was involved in moving illicit funds for the fugitive, Jho Low, involving the notorious looting of public funds in Malaysia. Jho Low has been accused by multiple jurisdictions of playing a key role in the embezzlement of more than $4.5 billion from a Malaysian economic development fund, 1MDB. JPMorgan Chase moved $1.2 billion in money for Jho Low from 2013 to 2016, according to the report.

The ICIJ report also found that JPMorgan “processed more than $50 million in payments over a decade…for Paul Manafort, the former campaign manager for President Donald Trump. The bank shuttled at least $6.9 million in Manafort transactions in the 14 months after he resigned from the campaign amid a swirl of money laundering and corruption allegations spawning from his work with a pro-Russian political party in Ukraine.”

Equally troubling activity at JPMorgan Chase includes the following, according to ICIJ investigators:

“JPMorgan also moved money for companies and people tied to corruption scandals in Venezuela that have helped create one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises. One in three Venezuelans is not getting enough to eat, the UN reported this year, and millions have fled the country.

“One of the Venezuelans who got help from JPMorgan was Alejandro ‘Piojo’ Isturiz, a former government official who has been charged by U.S. authorities as a player in an international money laundering scheme. Prosecutors allege that between 2011 and 2013 Isturiz and others solicited bribes to rig government energy contracts. The bank moved more than $63 million for companies linked to Isturiz and the money laundering scheme between 2012 and 2016, the FinCEN Files show…”

Wall Street firms like JPMorgan Chase are legally required to follow the “KYC” rule (Know Your Customer) in order to avoid moving money around for criminals. But the ICIJ investigators reveal that JPMorgan Chase paid little attention to that rule. The report found this:

“Take the case of a mysterious shell company called ABSI Enterprises. ABSI sent and received more than $1 billion in transactions through JPMorgan between January 2010 and July 2015, the FinCEN Files show.

“This amount included transactions through a direct bank account with JPMorgan, which ABSI closed in 2013, and through so-called correspondent banking arrangements, in which a bank with significant U.S. operations, such as JPMorgan, allows foreign banks to process U.S. dollar transactions through its own accounts.

“Compliance watchdogs based at the bank’s Columbus, Ohio operations hub decided to try to figure out ABSI’s actual owner in 2015 after a Russian news site reported that a similarly-named shell company — which JPMorgan’s records indicated was the parent of ABSI — was linked to an underworld figure named Semion Mogilevich.

“Mogilevich has been described as the ‘Boss of Bosses’ of Russia mafia groups. When the FBI put him on its Top Ten Most Wanted list in 2009, it said his criminal network was involved in weapons and drug trafficking, extortion and contract murders. The chain-smoking, beefy Ukrainian’s signature method of neutralizing an enemy, The Guardian once reported, is the car bomb.

“The records show the compliance officers searched in vain through their files on the shell company, unable to determine who was behind the firm or what its true purpose was.

“While those details still remain unclear, JPMorgan had plenty of reasons to examine ABSI years earlier: it operated as a shell company in Cyprus, considered a major money laundering center at the time, and it was directing hundreds of millions of dollars through JPMorgan…

“Through a spokesperson, Mogilevich said he had no knowledge of ABSI.”

The ICIJ investigation is hardly the first to find money laundering issues at JPMorgan Chase. On July 21, 2004, former Manhattan District Attorney Robert Mongenthau testified before the Senate Finance Committee on how JPMorgan Chase had moved money for an unlicensed money transmitting business called Beacon Hill Service Corporation. Morgenthau had this to say:

“Beacon Hill was an unlicensed money transmitting business, run out of offices on the seventh floor of a midtown Manhattan office building. It had about a dozen employees. Beacon Hill was open for business from 1994 to February 2003, when we executed a search warrant on the premises. In the last six years of its operation, this small company moved $6.5 billion, by wire transfers alone, through the 40 accounts it maintained at a major New York bank. [Court documents show that the bank was JPMorgan Chase.] This does not include checks, payable-through drafts or cash transactions. Beacon Hill was convicted in February 2004 of operating as a money transmitter without a license…

“Among the foreign authorities that have contacted the New York County District Attorney’s Office about the Beacon Hill accounts are Brazilian prosecutors and police and representatives of a special commission established in Brazil to investigate the movement of some $30 billion out of Brazil. The $30 billion is thought to be the proceeds of official corruption, government fraud, organized crime activities and weapons and narcotics trafficking. At least $200 million of this money – funds alleged to belong to a prominent public official in Brazil – moved through Beacon Hill’s accounts.”

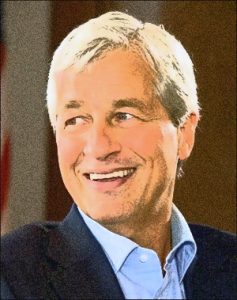

On January 7, 2014, JPMorgan Chase admitted to its first two felony counts. (The bank has since racked up a total of five felony counts in six years brought by the U.S. Department of Justice. The bank has admitted to all of its felonies while keeping the same Chairman and CEO, Jamie Dimon, giving the appearance that the felonies are a feature, not a bug, of its business model.) The bank’s first two felony counts were related to – wait for it – laundering money for Bernie Madoff, who was running the largest Ponzi scheme in history. The Department of Justice described part of what JPMorgan Chase had done as follows:

“Early on in its relationship with Madoff Securities, JPMorgan, because of its unique vantage point as the firm’s banker, had reason to be suspicious about Madoff. For example, in the early 1990s the Bank learned that Madoff and a prominent client of JPMorgan’s Private Bank (the ‘Private Bank Client’) were engaged in what looked like round-tripping, check-kiting transactions. Another bank involved in these transactions (‘Madoff Bank 2’) recognized them as suspicious and without any legitimate business purpose. In or about 1996, unlike JPMorgan, Madoff Bank 2 not only filed a suspicious activity report (‘SAR’) with law enforcement, but it actually closed down Madoff’s account. As a result, Madoff moved all of his accounts from Madoff Bank 2 to JPMorgan, where the size of these transactions became much larger. For example, in December 2001 alone, the Private Bank Client engaged in approximately $6.8 billion worth of transactions with Madoff through a series of circular $90 million transfers.”

That JPMorgan Chase Private Bank client was Norman F. Levy. Irving Picard, the Madoff bankruptcy trustee wrote in court documents that “during 2002, Madoff initiated outgoing transactions to Levy in the precise amount of $986,301 hundreds of times — 318 separate times, to be exact. These highly unusual transactions often occurred multiple times on a single day.”

In conjunction with the two felony counts, JPMorgan Chase had to pay restitution of $1.7 billion to a Madoff victims’ fund.