By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: May 14, 2020 ~

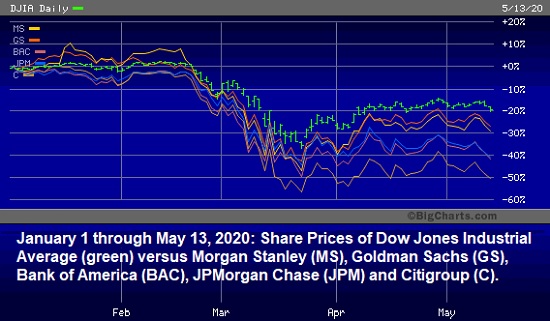

In the Federal Reserve’s most recent “Supervision and Regulation Report” on the big bank holding companies it “supervises,” the Fed continued its attempts to perpetuate the narrative that “The banking industry came into 2020 in a healthy financial position” and has simply unraveled as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. That narrative is built on the same flimsy house of cards that the New York Times and Andrew Ross-Sorkin built the narrative that the mega banks on Wall Street were not responsible for the 2008 financial collapse.

The Fed is desperate to promote this narrative to stop a new Congress next year from holding hearings on why the Fed, for the second time in 12 years, had to engage in trillions of dollars in Wall Street bank bailouts after reassuring Congress for years that the financial system was fine as the Fed loosened or rolled back reforms like the Volcker Rule. The Fed needs this narrative to prevail in order to cover up its own negligent supervision of the behemoth banks.

Depending on the composition of Congress next year, those hearings might bring about not only a restoration of the Glass-Steagall Act (which bans trading houses on Wall Street from combining with federally-insured, deposit-taking banks) but might also put an end to the Fed’s ability to negligently supervise the big banks with one hand, while bailing them out with the other hand, using money it creates out of thin air. (The Fed will report its latest balance sheet tally today at 4:30. It is expected to be close to $7 trillion from the $6.7 trillion it reported last week – which is $2.8 trillion more than it was exactly one year ago. The growth in the Fed’s balance sheet has come as a result of efforts to prop up Wall Street banks.)

The Fed knew, or should have known (since it has hundreds of people monitoring the markets at the New York Fed) that there was a big banking crisis brewing in August of last year. Here’s the timeline:

On August 8 Reuters reported that the amount of government bonds around the globe that were carrying negative yields had “increased to an all-time peak of $13.2 trillion.” This was an increase of 13.4 percent from just a month earlier. Large, rapid inflows into government bonds, which drives down the yield, signals a flight to safety, either from a brewing crisis or a brewing economic downturn, or both.

On August 14, the Wall Street Journal reported that “Investors continued their run on bank stocks, sending shares of some of America’s biggest financial institutions sharply lower following the latest sign of trouble ahead for the U.S. economy.”

On that day, August 14, the Dow Jones Industrial Average had plunged 800.49 points, or 3.05 percent but the shares of two of the biggest Wall Street banks, JPMorgan and Citigroup, significantly outpaced those losses. JPMorgan Chase lost 4.15 percent on the day while Citigroup gave up 5.27 percent.

Also on August 14, for the first time since the onset of the financial crisis in 2007, the U.S. saw an inversion of the yield curve, with the 2-year Treasury note yielding more than the 10-year note. This is viewed by market watchers as a harbinger of an impending recession.

Also notable on August 14, the Financial Times reported that Germany, Europe’s largest economy, had contracted in the second quarter and its annualized growth was now the slowest in six years.

On August 15, analysts at Zacks Equity Research wrote the following: “It has been about a month since the last earnings report for JPMorgan Chase (JPM). Shares have lost about 8.1percent in that time frame, underperforming the S&P 500.”

JPMorgan Chase is the largest bank in the U.S. It holds more than $1.6 trillion in deposits for businesses and moms and pops across America. On September 16, 2019 the U.S. Department of Justice announced that it had indicted three of the bank’s traders for turning its precious metals desk into a criminal racketeering enterprise. The bank’s traders, for the first time in history, were charged under the RICO statute, which is typically used to charge members of organized crime.

That would be bad news for any bank. But if you are already a three-count felon, as is JPMorgan Chase, it is excruciatingly bad news. In 2014 the U.S. Department of Justice charged the bank with two felony counts for the way it handled Ponzi-schemer Bernie Madoff’s business account for decades. The bank told U.K. authorities it thought Madoff was running a Ponzi scheme but failed to share that information with U.S. authorities. In 2015 the bank, along with other global banks, was charged with one criminal felony count for its role in rigging foreign exchange markets. JPMorgan Chase pleaded guilty to all three felony counts.

Apparently the Fed didn’t see any pattern here and allowed Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon to continue running the bank through three felony counts and the unprecedented racketeering charges of last year.

The very day after the U.S. Department of Justice brought the RICO charges, the Fed began an unprecedented intervention in the repo loan market as a result of a lack of liquidity which had driven overnight loan rates from about 2 percent to 10 percent in one day. By January 6, the Fed had admitted that it had made more than $6 trillion cumulatively in emergency repo loans to the trading houses on Wall Street. That was weeks before the first coronavirus outbreak had occurred in the United States.

For the Fed’s interventions from September 17, 2019 forward, see our ongoing series here.