By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: April 2, 2020 ~

Yesterday CNBC reported that Citigroup is one of the banks selected by the Small Business Administration to handle billions of dollars earmarked in last week’s stimulus bill to help small businesses get back on their feet and keep their employees paid during the coronavirus crisis. Citigroup’s Citicorp subsidiary was charged with, and pleaded guilty to, a criminal felony count brought by the U.S. Department of Justice on May 20, 2015 for its role in rigging foreign currency trading. Its rap sheet for a long series of abuses to its customers and investors since 2008 is nothing short of breathtaking. (See its rap sheet at the end of this article.)

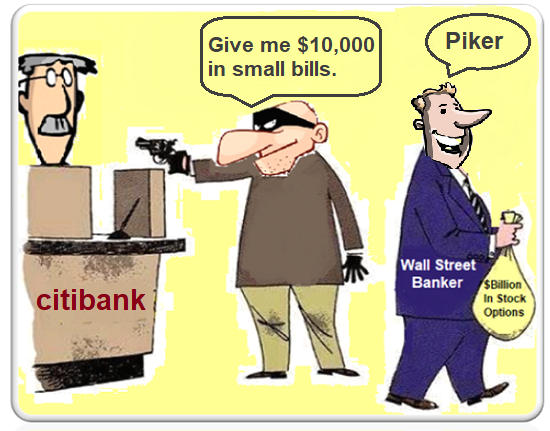

During the financial crash of 2007 to 2010, Citigroup received the largest bailout in global banking history after its former top executives had walked away with hundreds of millions of dollars that they cashed out of stock options. Citigroup received over $2.5 trillion in secret Federal Reserve loans; $45 billion in capital infusions from the U.S. Treasury; a government guarantee of over $300 billion on its dubious “assets”; a government guarantee of $5.75 billion on its senior unsecured debt and $26 billion on its commercial paper and interbank deposits by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

Sandy Weill was the Chairman and CEO of Citigroup as it built up its toxic footprint and off-balance-sheet vehicles that blew up the bank. Weill was also the man who engineered the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, the depression-era legislation that had safeguarded the U.S. banking system for 66 years before its repeal in 1999. Weill needed the Glass-Steagall legislation to vanish so that he could merge his hodgepodge of Wall Street trading firms (Salomon Brothers and Smith Barney, et al) with a federally-insured bank full of deposits. Weill told his merger partner, John Reed of Citibank, that his motivation for the deal was: “We could be so rich,” according to Reed in an interview with Bill Moyers.

The repeal of Glass-Steagall meant that the casino-style investment banks and trading houses across Wall Street could now own federally-insured commercial banks and use those mom and pop deposits in a heads we win, tails you lose strategy. Every major Wall Street trading house either bought a federally-insured bank or created one. (See the co-author of this article testifying before the Federal Reserve on June 26, 1998 against the Citigroup merger and the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in this video.)

What Weill meant by “We could be so rich” was this: If the trading bets won big, the CEOs became obscenely rich on stock-option-based performance pay. When the bets lost big, the government would be forced to do a bailout rather than allow a giant federally-insured bank to fail. This is why the Federal Reserve had to secretly plow $29 trillion into Wall Street banks and their foreign derivatives counterparties between 2007 and 2011 and why the Fed had to open its money spigot again on September 17 of last year – months before there were any reports of coronavirus COVID-19 cases anywhere in the world.

Sandy Weill became a billionaire at the merged Wall Street bank, known as Citigroup, through a technique that compensation expert Graef “Bud” Crystal called the Count Dracula stock option plan – you simply could not kill it; not even with a silver bullet. Nor could you prosecute it, because Citigroup’s crony Board of Directors rubber-stamped it. The plan worked like this: every time Weill exercised one set of stock options, he got a reload of approximately the same amount of options, regardless of how many frauds the bank had been charged with during the year. (And there were plenty. See rap sheet below.)

Writing at Bloomberg News, Crystal explained that between 1988 and 2002, Weill “received 96 different option grants” on an aggregate of $3 billion of stock. Crystal says “It’s a wonder that Weill had time to run the business, what with all his option grants and exercises. In the years 1996, 1997, 1998 and 2000, Weill exercised, and then received new option grants, a total of, respectively, 14, 20, 13 and 19 times.”

When Weill stepped down as CEO in 2003, he had amassed over $1 billion in compensation, the bulk of it coming from his reloading stock options. (He remained as Chairman of Citigroup until 2006.) Just one day after stepping down as CEO, Citigroup’s Board of Directors allowed Weill to sell back to the corporation 5.6 million shares of his stock for $264 million. This eliminated Weill’s risk that his big share sale would drive down his own share prices as he was selling. The Board negotiated the price at $47.14 for all of Weill’s shares.

On May 9, 2011 Citigroup did a 1 for 10 reverse stock split, meaning if you previously owned 100 shares of Citigroup, you now owned just 10 and the price was adjusted upward accordingly. At yesterday’s closing price of $38.51 (actually $3.85 if adjusted for the reverse stock split), Citigroup’s long-term shareholders are still down 92 percent from where Weill bailed out of the stock in 2003.

Another man that became obscenely rich from Citigroup was Robert Rubin, the Treasury Secretary under the Bill Clinton administration who helped Citigroup advocate for the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act. Without any meaningful cooling-off period, Rubin went straight from his government post to serve on the Board of Citigroup. Rubin received more than $120 million in compensation over the next eight years for his non-management job.

John Reed had a falling out with Weill and retired from Citigroup in April 2000. In Monica Langley’s book, Tearing Down the Walls: How Sandy Weill Fought His Way to the Top of the Financial World. . .and Then Nearly Lost It All, the author reports that Reed owned 4.7 million shares of Citigroup on the date of his retirement. Langley also writes that “Reed immediately began selling his Citigroup shares and laid plans with his second wife to buy a house on an island off the coast of France.”

If Reed sold all of his Citigroup shares over the next three months after his retirement at an average price at the time of $62, he would have realized $291 million in proceeds. According to SEC filings (see here and here) Reed also received a $5 million retirement bonus and a retirement pension of at least $2,019,528 annually.

According to the SEC filings, Reed was also to receive the following: lawsuit indemnifications arising from company employment; an office at Citigroup, secretarial support and access to a car and driver for as long as Reed deemed it “useful.” If Reed decided he needed an office outside of New York City, that would be provided with secretarial support until age 75.

When Weill stepped down as CEO in 2003, he put his General Counsel and personal friend, Chuck Prince, in charge as CEO. Prince took the fall when the company imploded in 2008. For being a good foot soldier to Weill, Prince got an exit package of $68 million.

And then there was Vikram Pandit, a hedge fund manager whom Robert Rubin selected to run the sprawling Citigroup. The Wall Street Journal reported that Pandit took home $221.5 million during his five years at Citigroup.

Sheila Bair, the head of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation that guaranteed Citigroup’s debt during the financial crisis, wrote this about Pandit’s persona at a meeting with other bankers in her book “Bull by the Horns”:

“Pandit looked nervous, and no wonder. More than any other institution represented in that room, his bank was in trouble. Frankly, I doubted that he was up to the job. He had been brought in to clean up the mess at Citi. He had gotten the job with the support of Robert Rubin, the former secretary of the Treasury who now served as Citi’s titular head. I thought Pandit had been a poor choice. He was a hedge fund manager by occupation and one with a mixed record at that. He had no experience as a commercial banker; yet now he was heading one of the biggest commercial banks in the country.”

When the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission concluded its findings into what led to the financial crash of Wall Street in 2008, resulting in millions of job losses and foreclosures across America, it made numerous referrals for potential criminal prosecutions to the Justice Department. Three of Citigroup’s executives were among those referrals: Robert Rubin, Chuck Prince and former CFO Gary Crittenden. Nothing ever became of those referrals.

In 2012 the law firm Kirby McInerney agreed to settle a lawsuit against Citigroup on behalf of shareholders for $590 million. The lawsuit charged that Citigroup had lied to shareholders about its financial condition, including its losses from off-balance-sheet accounting tricks. The plaintiffs wrote this about Citigroup’s Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs), which were loans to lower credit-rated companies that were then pooled together:

“After purchasing insurance on a CLO tranche, Citigroup would book the difference in the cost of the insurance and the payments of the loan for the entire life of the loan immediately as if the loan had been sold…Additionally, Citigroup engaged in negative basis trades with the billions of dollars of CLO exposure remaining on the Company’s balance sheet. These trades allowed Citigroup to book immediate gain for the entire term of loans by purchasing insurance on their default and, thereby, treat the purchase of insurance as a sale of the loans when, in fact, those loans (or rather, those CLO tranches) never left Citigroup’s books…In addition to the high fees for CLO creation, the ability to create instant gain through these trades was a powerful incentive for Citigroup to issue ever riskier leveraged loans. While revenue from fees and negative-basis trades inflated Citigroup’s earnings on leveraged loans and CLOs, Citigroup kept its shareholders unaware of the artificial source of the gains or the inherent risks in continuing to operate its ephemeral money-making machine.”

After Citigroup’s massive bailout by taxpayers and the Federal Reserve, its crime spree continued. This is just a sampling of charges brought against Citigroup and its affiliates since December 2008:

Citigroup’s Rap Sheet:

December 11, 2008: SEC forces Citigroup and UBS to buy back $30 billion in auction rate securities that were improperly sold to investors through misleading information.

July 29, 2010: SEC settles with Citigroup for $75 million over its misleading statements to investors that it had reduced its exposure to subprime mortgages to $13 billion when in fact the exposure was over $50 billion.

October 19, 2011: SEC agrees to settle with Citigroup for $285 million over claims it misled investors in a $1 billion financial product. Citigroup had selected approximately half the assets and was betting they would decline in value.

February 9, 2012: Citigroup agrees to pay $2.2 billion as its portion of the nationwide settlement of bank foreclosure fraud.

August 29, 2012: Citigroup agrees to settle a class action lawsuit for $590 million over claims it withheld from shareholders’ knowledge that it had far greater exposure to subprime debt than it was reporting.

July 1, 2013: Citigroup agrees to pay Fannie Mae $968 million for selling it toxic mortgage loans.

September 25, 2013: Citigroup agrees to pay Freddie Mac $395 million to settle claims it sold it toxic mortgages.

December 4, 2013: Citigroup admits to participating in the Yen Libor financial derivatives cartel to the European Commission and accepts a fine of $95 million.

July 14, 2014: The U.S. Department of Justice announces a $7 billion settlement with Citigroup for selling toxic mortgages to investors. Attorney General Eric Holder called the bank’s conduct “egregious,” adding, “As a result of their assurances that toxic financial products were sound, Citigroup was able to expand its market share and increase profits.”

November 2014: Citigroup pays more than $1 billion to settle civil allegations with regulators that it manipulated foreign currency markets. Other global banks settled at the same time.

May 20, 2015: Citicorp, a unit of Citigroup becomes an admitted felon by pleading guilty to a felony charge in the matter of rigging foreign currency trading, paying a fine of $925 million to the Justice Department and $342 million to the Federal Reserve for a total of $1.267 billion. The prior November it paid U.S. and U.K. regulators an additional $1.02 billion.

May 25, 2016: Citigroup agrees to pay $425 million to resolve claims brought by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission that it had rigged interest-rate benchmarks, including ISDAfix, from 2007 to 2012.

July 12, 2016: The Securities and Exchange Commission fined Citigroup Global Markets Inc. $7 million for failure to provide accurate trading records over a period of 15 years. According to the SEC: “CGMI failed to produce records for 26,810 securities transactions comprising over 291 million shares of stock and options in response to 2,382 EBS requests made by Commission staff, between May 1999 and April 2014, due to an error in the computer code for CGMI’s EBS response software. Despite discovering the error in late April 2014, CGMI did not report the issue to Commission staff or take steps to produce the omitted data until nine months later on January 27, 2015. CGMI’s failure to discover the coding error and to produce the missing data for many years potentially impacted numerous Commission investigations.”

June 15, 2018: Citigroup agrees to settle with states for $100 million over charges that it rigged the Libor interest rate benchmark.

June 29, 2018: Citigroup’s Citibank settles with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau for $335 million in restitution to credit card customers over charges that it violated the Truth in Lending Act.

August 16, 2018: Citigroup settles with SEC for $10.5 million over inadequate controls, mismarking of illiquid positions and unauthorized proprietary trading.

September 14, 2018: Citigroup settles with SEC for $13 million over charges it improperly operated its Dark Pool – an internal stock exchange where it is allowed to trade its own stock.

May 22, 2019: Citigroup settles a money laundering case with the U.S. Department of Justice for $97.44 million.

November 26, 2019: Citigroup settles with the Bank of England’s Prudential Regulatory Authority for $57 million over charges that it incorrectly reported the bank’s capital and liquidity levels.