By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: November 19, 2019 ~

According to the most recent statistical release from the Federal Reserve, the average annual interest rate on 90-day AA-rated financial commercial paper has risen from 2.18 percent in 2018 to 2.27 percent through November 15 of this year. The rise in the average annual interest rate on 90-day commercial paper contrasts with the fact that since May of this year, the 90-day (3-month) Treasury bill’s yield has moved sharply lower, from 2.4 percent to yesterday’s closing yield of 1.56 percent – a decline of 35 percent.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York has effectively become the repo market – pumping out upwards of $3 trillion to that market since September 17. Can we expect the Fed to turn on the money spigot to the commercial paper market next?

We raise this scenario because that’s exactly what the Fed did to the tune of almost $1 trillion from the fall of 2008 to February 1, 2010 during the financial crisis.

On September 19, 2008, four days after the bankruptcy filing of Lehman Brothers, the Fed created the Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (AMLF). The Fed then proceeded to pump out $217 billion under that facility until February 1, 2010, ostensibly so that banks could buy up asset-backed commercial paper from money market funds that had been tainted with subprime loans in order to prevent a panic run on those funds. According to the audit conducted by a federal agency, the Government Accountability Office (GAO), $111 billion of AMLF funds went to JPMorgan Chase.

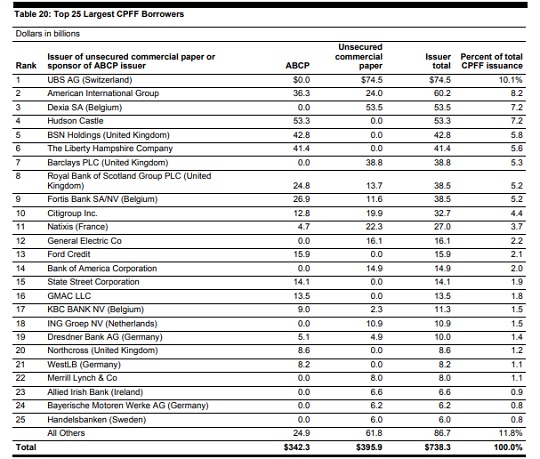

The AMLF wasn’t enough to stem the problems in the commercial paper market so 18 days after the Fed created the AMLF it announced the creation of the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF). That program operated from October 27, 2008 until February 1, 2010. Through that facility the Fed pumped out $738 billion in loans to a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) that made outright purchases of commercial paper.

The GAO explains the purpose of the CPFF like this:

“By standing ready to purchase eligible commercial paper, CPFF was intended to eliminate much of the risk that commercial paper issuers would be unable to ‘roll over’ their maturing commercial paper obligations—that is, they would be unable to repay maturing commercial paper with a new issue of commercial paper. By reducing this roll-over risk, CPFF was expected to encourage investors to continue or resume their purchases of commercial paper at longer maturities.”

As the CPFF chart from the GAO audit shows (see chart below), two of the three largest borrowers under the facility were foreign. UBS of Switzerland got $74.5 billion while Dexia SA of Belgium received $53.5 billion. Sixty percent of the top 25 borrowers were foreign financial institutions. Undoubtedly, many of those institutions were in trouble with their commercial paper because they had purchased subprime toxic debt bombs from Wall Street banks. Thus, an unstated purpose of the CPFF was to salvage the reputation of Wall Street and lessen the number of lawsuits over toxic debt issuance.

The official report from the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC) adds further sunshine into why the ruptures in the commercial paper market were spilling back onto the balance sheets of the Wall Street banks and creating a panic. The FCIC writes:

“…the rating agencies had given all of these ABCP [Asset-Backed Commercial Paper] programs their top investment-grade ratings, often because of liquidity puts from commercial banks. When the mortgage securities market dried up and money market mutual funds became skittish about broad categories of ABCP, the banks would be required under these liquidity puts to stand behind the paper and bring the assets onto their balance sheets, transferring losses back into the commercial banking system.”

In 2010, Alexander Mehra penned a detailed analysis for the University of Pennsylvania Journal of Business Law on the Fed’s actions during the financial crisis. His analysis was that the Federal Reserve had exceeded its legal authority under the Federal Reserve Act in conducting a number of its Wall Street bailout programs. One of those programs that came under his radar was the CPFF. Two of Mehra’s key problems with the CPFF were that the Fed is only empowered to make “loans” against “endorsed or secured” collateral. In the case of the CPFF, the Special Purpose Vehicle set up by the New York Fed was making outright purchases of “unsecured” commercial paper.

The vast majority of the $29 trillion in programs to bail out Wall Street during the financial crisis were operated out of the New York Fed – just one of the 12 regional Federal Reserve banks, but the only one with its own trading floor and the only one owned by the largest Wall Street banks. Today, it’s also the New York Fed that is pumping out hundreds of billions of dollars each week to unnamed trading houses on Wall Street for a repo loan crisis that has yet to be explained or defined in any credible terms.

Last week CNBC’s Rick Santelli asked Jim Grant, Editor of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, if the Fed had effectively nationalized the repo market. (Nationalization means a government takeover.) Since the upwards of $3 trillion in repo loans since September 17 has come out of the New York Fed, and it is owned by Wall Street banks, perhaps the question should be if Wall Street, via the New York Fed, has privatized the repo loan market.

A similar question could be asked of the commercial paper market during the financial crisis. Was that privatized by Wall Street, via the New York Fed which has somehow gained the power to create trillions of dollars by pushing an electronic button.

It’s now been 63 days since the New York Fed opened its repo money spigot again for the first time since the financial crisis. In those 63 days not one Congressional hearing has been called to drill down to what the crisis is and if it’s spreading. The American people deserve far better than this from their elected representatives.